Have you ever tried to do the impossible? I don’t mean something that feels impossible, but which you know, deep down, you could really do if you had to (like binge-watch the entire corpus of Breaking Bad in a single three-day weekend—wait! what?!).

I mean, have you ever been asked by someone to do a certain project, the scope and magnitude of which, at least to casual observers, seemed staggeringly impossible? Do you know Lonnie Bunch III? You should.

Dr. Bunch is the Founding Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Afican American History and Culture. That job sounds really cool (it is), but the title obscures what was required to bring the museum to fruition. Recounting this struggle—and no, that word is not an overstatement—is beyond the scope of what I want to write here, but Bunch’s memoir, A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, Trump, presents a richly textured recounting of what “impossible” looks like, and how he overcome it thanks to creativity, thoughtfulness, candor, courage, and the conviction that our shared past, present, and future must be faced squarely.

The staggering breadth of Bunch’s charge—to realize the building of a museum dedicated to African American history and culture on the National Mall in Washington,DC,—is perhaps best understood by letting the author speak for himself. “I realized that my job,” he writes,

“ultimately was to make an array of people, potential funders, Congress, average citizens, and Smithsonian colleagues, believe, truly believe, that a museum would arise on the Mall, believe that millions of dollars could be raised, believe in the redemptive power of history, and in my leadership and vision. A tall order.” (Emphasis added.)

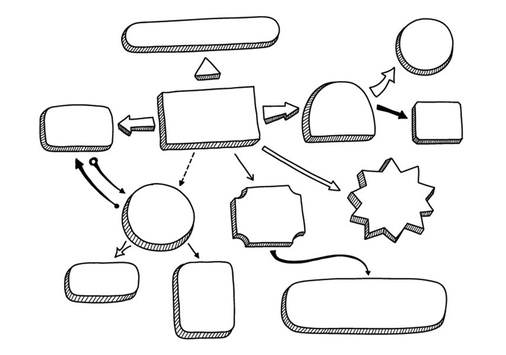

The book chronicles the ways Bunch sustained the energy, vision, wherewithal, and conviction to secure the funding, supervise the building, and oversee the curating of the museum. It all began, as the very best collaborations do, with a vision for a framework in which the NMAAHC would move from an idea to become the crown jewel of the National Mall.

Bunch and his colleagues were convinced the museum could not be a mere space for “memorable objects and exhibitions.” Their vision had to be bigger. But the tinge of the impossible lingered. Could the museum really be, as he reflects, “a site of transformation that would make America better,” a space to help “bridge the chasms like race that have divided America since its inception”? Could it “allow America to hear the voices of people who had long been undervalued, or ignored”? A site for “debate and difficult conversations, but a setting that embodied the meaning of Langston Hughes’s words, ‘not without laughter’”? A tall order, indeed.

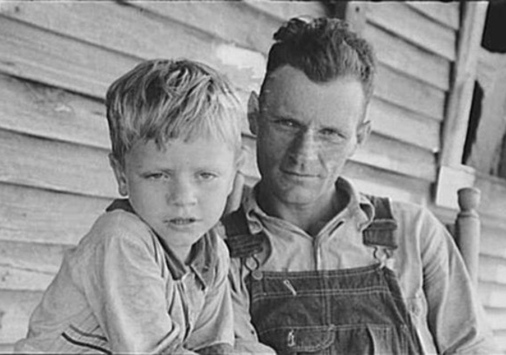

I have visited the museum twice and been overwhelmed by its horror and hope, its pain and possibility, its unvarnished truth-telling that permeates every single inch of its five floors. And I have wondered recently, as I’ve sat with Bunch’s memoir and reflected on my experiences directing the Center for Learning and Teaching, the ways teaching embodies the impossible task he surmounted.

Please don’t misunderstand: I’m not saying the challenges in my classroom rival what Bunch overcame. (He opened the museum in just ten years time!) Scale matters, and I have no illusions that my job rises to the same levels of importance, difficulty, or magnitude as Bunch’s. But if comparisons prompt humility, they also spur solidarity, a bonding grounded in the realization that in our teaching each of us does something wonderfully, staggeringly impossible.

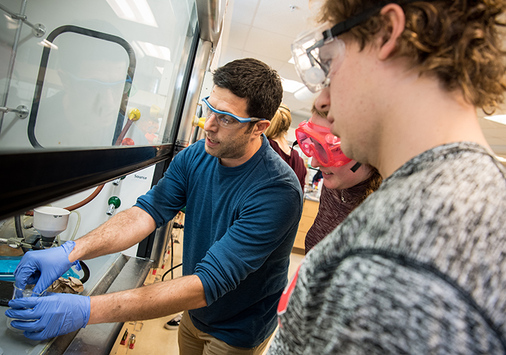

It’s become the coin of the realm in national conversations about faculty development to talk at length about student learning. These conversations, on the one hand, seem exactly right. There is much to learn from thinking about the principles of meta-cognition, the science of memory and retrieval, and the ways the brain creates patterns and corresponding strategies and habits by which learning is maximized.

On the other hand, I worry that our brains get ahead of our hearts, and the love, passion, courage, and conviction which make teaching as much an art as a science. I’m not saying you must choose sides; that seems silly. But I am saying, in echo of Bunch’s remarkable example, that the so-called “vision thing” profoundly matters.

Maybe what makes the impossible possible—connecting with students in ways that result in them feeling our excitement, curiosity, and sense of wonder; in fostering those connections in ways characterized by mutual respect, a commitment to belonging, and a sense of grace—is that, first, we have to believe. We have to believe our students want to learn, believe that what we study matters, believe that regardless of the gnashing of teeth happening beyond our studios, labs, and classrooms, regardless of what the “data” and the science allege, regardless of the jangling chords of self-doubt keeping us awake at night, we have to believe.

To teach, finally, is an act of outrageous faith. Each of us has within us the will to do the impossible. Don’t believe me? Fine. Are you really going to doubt Lonnie Bunch?