Since rediscovering his love of piano at Denison and learning to compose the music he now plays, Rumi Kang ’26 has worked toward an ambitious goal.

He wants to write a piano concerto.

“It was the next natural step,” says Kang, a mathematics and music composition double major. “I want to be part of the club. I need to be part of the cool kids club.”

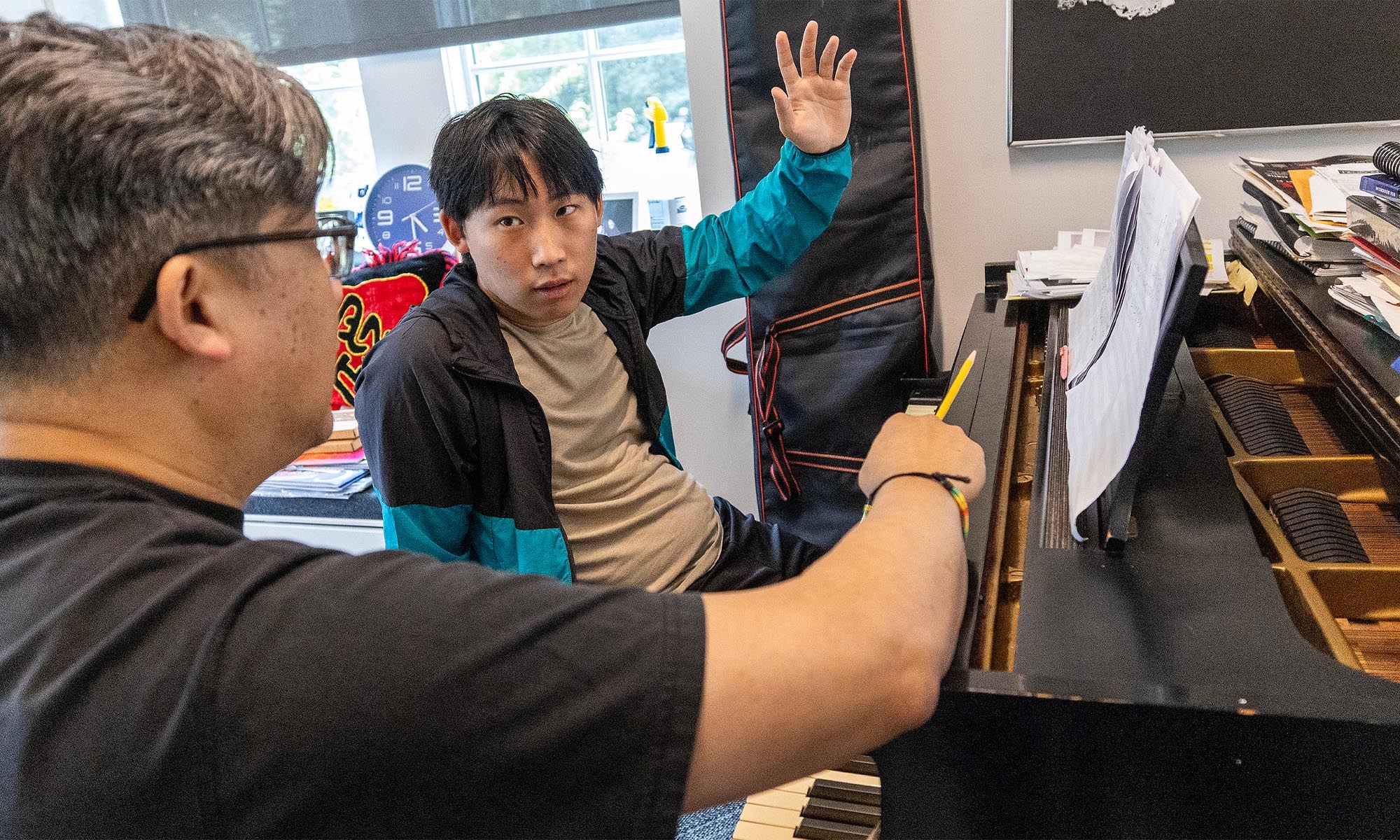

Note by note, and revision after painstaking revision, the opening movement of Kang’s concerto takes shape in the office of professor Ching-chu Hu. Seated behind a Steinway piano, Kang fills the room with the melodies of his creation, eager to hear his professor’s feedback.

Hu, an award-winning composer, agreed to oversee Kang’s 10-week Summer Scholars project because he appreciates the student’s desire and the good ideas he brings to the art of composition.

“The great thing about Summer Scholars is you have time to devote to the work,” says Hu, director of music theatre and Vail Series coordinator. “Rumi doesn’t have to worry about doing homework or taking a test for another class. He can marinate in his ideas all day.”

Kang’s mother encouraged him to take piano lessons at age 9, and he played into high school before his interest waned. It reignited during his first semester at Denison as his roommate introduced him to Logic Pro, a digital audio workstation that provides software instruments, and recording facilities for music synthesis. Kang took a music composition class in his second semester and was hooked.

He started scoring small-scale pieces, wrote music for the string quartet ETHEL, and supplied material for the Newark-Granville Symphony Orchestra and its performances at the Licking County Library during children’s book readings.

Kang understood composing a piano concerto, which includes writing for 25 other instruments, was a different musical beast. It’s been a rewarding, maddening, enriching, and educational experience.

The student works throughout the week and meets with Hu, who offers valuable insight into ways Kang can improve the piece. They both laugh at the memory of Kang arriving for the start of the summer project having already written more than five minutes of his concerto, spanning at least 20 pages.

“We stretched it out across the office floor and it was like a snake,” Hu says.

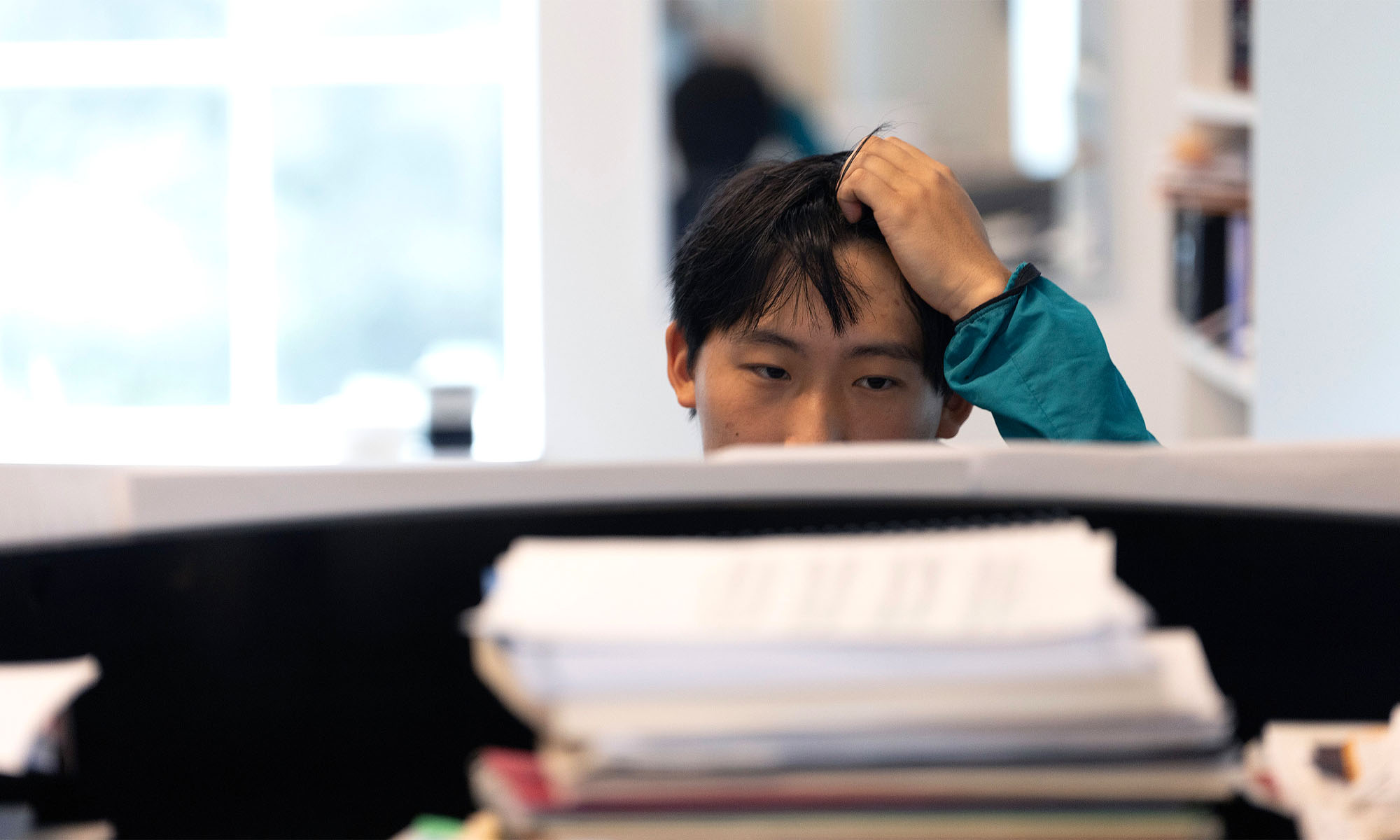

The professor doesn’t expect Kang to finish the concerto by summer’s end. It will likely turn into his senior project. Hu wants his student to trust the process necessary for longer pieces. It requires Kang to show all his work, commit to writing on paper instead of a computer — Mozart and Beethoven didn’t need a laptop — and carry a big eraser.

Kang generates lots of creative ideas but often ditches them when hitting a roadblock. Hu discourages him from self-censoring.

“I’ll use a juice analogy,” Hu tells Kang. “You bring in all this fruit, and you’re only giving it one squeeze sometimes. There’s so much more juice in there. Develop your ideas. There is no wasted work.”

Kang is challenging himself like never before. He is constantly arranging and rearranging, a tedious process without the benefit of a delete button. But the sense of achievement is evident when Hu offers praise for the work.

The student is grateful that an accomplished musician like Hu is dedicating so much time to Kang’s effort. As the professor makes a recommendation, something inside the student clicks.

“Oh, I never thought about it that way,” Kang says. “That’s a good idea.”

He plays a new series of notes and quickly jots them down with a pencil.

“The main thing is you’re introducing us to your world, your color, your style, your motive,” Hu says of Kang’s first movement. “You want to be very concise with what you are saying at first. Then you start developing it, and we’ll be along for the ride.”