Let’s start with a truth: Working from home hasn’t proved easy. My reasons why won’t interest you, but full confession: I made three occasions to go to the office, in gentle defiance of our state’s stay-at-home order, just for a change of scenery. And, admittedly, I didn’t get much work done there either. But on my bookshelf, I did find Remaking College: Innovation and the Liberal Arts (2016), a smart, insightful volume edited by Rebecca Chopp, Susan Frost, and Daniel H. Weiss. Re-reading some of its collected essays, principally authored by presidents at some of America’s very finest liberal arts colleges, spurred me to reflect on my three years directing the Center for Learning and Teaching, and to wonder, in echo of the book’s introduction: Are schools like Denison resilient enough to survive this moment in which we find ourselves?

On the heels of the truth above, two omissions, both from the book by Chopp and her colleagues. The index (what, you think academics don’t read indexes more carefully than warnings on bleach labels?) makes absolutely no mention of President Donald Trump or the coronavirus.

Admittedly, the first omission is easy to understand: Though published in 2016, the majority of the volume’s chapters stemmed from a conference Chopp and Weiss organized in 2012 at Lafayette College (Easton, PA), its title perhaps more grand even than its promise: “The Future of the Liberal Arts College and Its Leadership Role in Education around the World.”

While the 45th president is not mentioned, the chapters, spanning such things as the history of the liberal arts, economic and affordability challenges, shared governance, technology, and the cultures of learning distinct among SLACs (small liberal arts colleges), do frequently invoke values that have assumed urgent concern over the four years he has mangled the presidency; as with the office, so too has the summarily mangled many of these values: civility, the common good, diversity, globalism, and sustainability.

The omission of the coronavirus also is easy to understand. Yet its absence from the book and its ominous presence in our waking lives and our darkest nightmares combine to make assertions like this one all the more provocative:

The contemporary [liberal arts college] is a surprising case study in flexibility, strength, and irrepressibility, all key components of the kind of resilience that individuals and institutions need in the twenty-first century.

Re-reading these words prompts me to wonder: That was then. What about now?

The question is one that might be shared by Brian Rosenberg, whose playfully titled chapter, “The Liberal Arts College Unbound,” throws down the proverbial gauntlet when he notes how he “cannot escape the sense that economics and technology are combining to create a transformational moment in higher education and that the traditional liberal arts college will be most viable and most valuable if it can use its inherent advantages.” Let it be known, I dearly want to share his faith.

Of course, economics and technology are ever-present actors in the sordid drama presently unfolding across these United States, a drama best understood as tragic in its scope and consequence. (What is a vaccine, after all, if it is not most significantly a kind of medical technology through which healing intervention is realized?) As I write this essay, over 58,000 people have died from COVID-19, more than the number of American fatalities during the Vietnam War.

The confluence of an unfit president and a relentless virus have seemingly put at dire stake the very prospects of liberal arts colleges like ours. I am, of course, wholly unoriginal in my Cassandra-sounding dread. Indeed, it has become next to impossible to keep apace of the flow of ink (digitally spilled, or course) blotting on about why campuses must open in the fall, and, if we can, what changes may be necessary to square the experiences of students with the histories and traditions of small liberal arts colleges. Indeed, many writers wonder whether and if higher education ever will be the same again.

Beyond the wrenching uncertainty the virus compels, our commonweal is wholly and thoroughly fractured. And while every-day persons and groups and institutions are trying, fervently, earnestly trying to repair broken bonds between us, the damage precipitated by a man-child playing at politics has rent our national life in ways that seem almost nearly beyond repair.

So, then, another confession: I will not pretend to know the way through. I cannot forecast how and whether Denison should resume on-campus classes in the fall. I know not whether the current occupant of the People’s House will be re-elected. And I can’t confidently predict the ways education may change as we settle into the aftermath of the pain and havoc and heartbreak caused by an unforgiving virus and a malignant civic ethos that has rent our common life.

But when I imagine what tomorrow looks like (and it is an undeniable fact—tomorrow will come), I feel my dread consumed by hope. This hope, to be clear, is not some dewy-eyed optimism. The road ahead will be hard. Undeniably, excruciatingly hard. But if we key on three things, I think schools like Denison, our school and everything it means to us in this perilous moment, will in fact find new ways to thrive. That thriving will depend on embracing three truths:

1. The resiliency of our students has proved absolutely remarkable and the way forward will continue to demand undaunted courage and boundless curiosity.

Colleges must do everything at their disposal to reaffirm and sustain living-learning environments characterized by intellectual curiosity and challenge; humane, life-giving creativity; and an unapologetic commitment to the moral formation of students’ character within the context of a diverse, inclusive, and brave community for whom common purpose is the glue that bonds them. As Chopp pleaded in 2012 (and surely in 2020 this clarion call’s urgency breaks through petulant claims of tribe or clique or cause):

This reality offers an immense opportunity for our students, faculty, and staff—one that very few other institutions can meet. Our country is in desperate need of what the liberal arts can offer. A serious crisis deeply linked to the failure of individuals in democratic communities to find common ground is leading many citizens to lose faith in their leaders, in their democratic institutions, in their communities that are increasingly polarized, and in the long-held sense of the common good. (Emphasis added.)

2. Colleges must double-down on all manner of holistic faculty development. Now. Without exception.

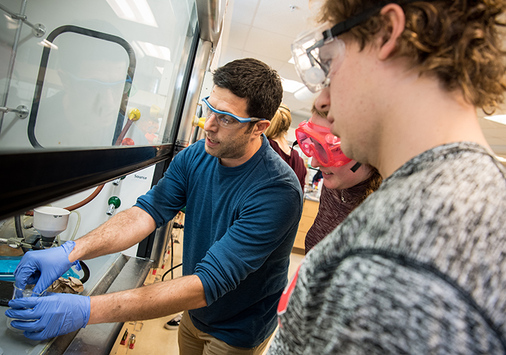

Required now more than ever is a renewed, concerted attention not only to equipping faculty with the tools with which to tinker at designing and delivering curricula, but with providing humane structures of support and genuine incentives informed by the highest communal values. It is through these reimagined, and reinvigorated, structures that faculty may live professional lives characterized by wholeness—a combination of rigor and compassion, joy and courage woven together in ways that result in our most authentic selves. In the throes of this wholeness we will find that the work of our work is most properly regarded not merely as a job or even as a profession, but as a calling, one that, at its core, seeks not simply to create and share knowledge but aspires to something altogether more daring: the transformation of lives.

3. Because an indifferent virus has stripped away nearly everything that marks college as “college,” we now must cleave to what is resolutely essential when campuses return to face-to-face instruction: the dedicated cultivation of citizen-professionals invested in the commonweal.

Higher education must stop mindlessly fixating on “learning outcomes” and whether and if “learning sticks.” Of course we are and shall always be an academic institution, and learning and its pride of place must hold. Yet what must become primary and absolute is the recognition that if we do not challenge students to embrace the common good, that this good will suffer, first from benign neglect, and ultimately from the bludgeoning which follows atomistic convictions that learning, memory, and so-called cognitive mastery somehow supersede compassion, decency, kindness, joy, and courage. These, finally, are intellectual virtues of the highest order, as Sewanee President John Malcolm McCardell, Jr., elegantly noted about liberal education. Such an education, “broadly understood,” he wrote, “includes the creation and nurturing of communities of learning, [where] we go about our work shaping each individual life to ends that are educational, of course, but more—purposeful, informed, loving, selfless, perhaps even (or what’s a heaven for?) noble.” What is a heaven for, indeed.

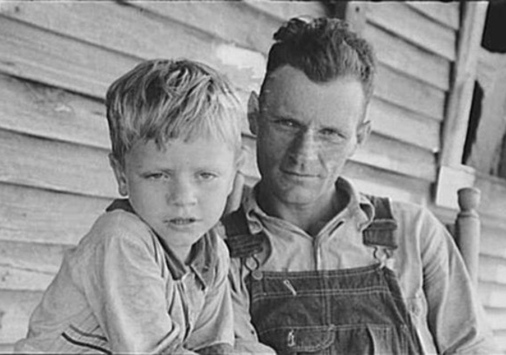

The late William G. Bowen, former president of the Andrew Mellon Foundation and Princeton University, and perhaps most importantly a Denison alum (Class of 1955), while sympathetic to McCardell’s conviction, provides a sober realism that is not without warrant: “There is,” he intones in the final chapter of Remaking College, “an all-too-real limit to what colleges can do to shape the thinking of their students. But it is well to recognize that colleges, at their best, can and should encourage their students to learn to choose wisely—and to learn to be kind.” (Emphasis added.) Born in the midst of the Great Depression, Bowen over his lifetime would witness a nation mired in gut-wrenching poverty, consumed by a World War and military actions in Korea and Vietnam, overwhelmed by trenchant struggles for civil rights and reproductive freedoms and basic human dignity, and rendered almost paralyzed by the persistent degradation of the earth. He died less than three weeks before the election of a clownish huckster for whom the presidency would become a stage on which to act out the pathetic trappings of celebrity under the soft-faced guise of tyranny. And yet. While I would never speak for Bowen, his closing remark about the future of liberal arts colleges would seem to apply to so much more: There is, he insisted with characteristic understatement, “without question, more to hope than to fear.” (Emphasis added.)

The work of centers for learning and teaching, the work of faculty development more generally, is richly rewarding. My kin go to work each day (well, most recently we’re staying squarely at home—but we’re working!) keen to make a difference. This motivation stems not from ego but from a genuine desire to give back. I have benefited from mentors who patiently (if exasperatingly) counseled me to think hard about my teaching and to put my students’ learning first. They gave selflessly of their time and insight. I have tried to honor their examples. I fear I still have much to learn. My mentors also challenged me to tell the truth. I fear that too often I have disappointed them on this score as well. But I will try once more. So then, finally, this: The wolves are at the door. The house is on fire. We are in this together or we are not. We must choose. We must choose one another. We must, finally, choose hope.

Over the three years that I have had the privilege to direct the Center for Learning and Teaching I have benefitted immensely from the insight, advice, example and courage of colleagues for whom learning and teaching mean nearly everything. Their professionalism has inspired me; their generosity has astounded me. I cannot name everyone here, for sheer fear that I would inadvertently, painfully, leave someone out. I am deeply thankful for all of the support I have experienced across all sectors of campus. I regret only the ways I fell short of your expectations or did not execute my job in ways you had hoped. Of course, perfection is its own idol, and if I’ve learned nothing over these last agonizing weeks and days and hours, it is long past time to begin smashing idols. And still: I am genuinely grateful to everyone.