I have never met Dr. Jeff Duncan-Andrade, associate professor of education administration at San Francisco State University, but we have dreamt the same dream. Like him, I wanted to be a professional basketball player. I idolized Isiah Thomas, the preternatural point guard for the Detroit Pistons whose game, to my adolescent eyes at least, was a stunning combination of creativity, grace, and verve (though as an adolescent I couldn’t have defined “verve” for you). I wore his number 11 as my own; it was both signifier and totem: I was a different player because his jersey number imbued me—or so I thought—with an on-court audacity that made me feel anything was possible.

Nostalgia is a dangerous tonic, but I think it may be the case that I felt my most alive, something like my most authentic “self,” when I played basketball. It’s a feeling I’ve never been able to replicate since I ceased playing in my late twenties. The feeling’s absence is a loss I mourn and confirmation of an unshakeable realization: Time does not stop and it does it care what I care about it. And, thankfully, we go on living.

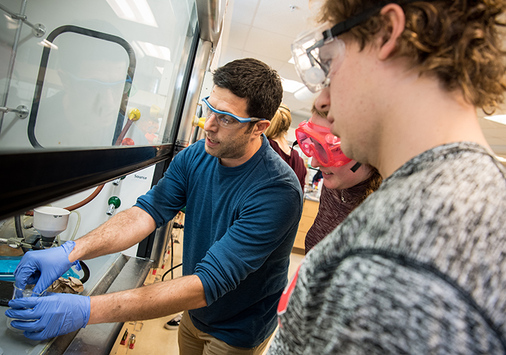

While Dr. Duncan-Andrade had the sorts of success as a basketball player I never knew (I was not talented enough for elite travel teams), our love for the game is not the only thing that binds us. Like him, I am keenly interested in the aims of education. His work concentrates specifically on public school districts and the ways a commitment to the “hyperlocal” dimensions of public education may improve the overall educational experiences of students who attend school in a particular neighborhood, in a particular community.

For Duncan-Andrade, in other words, mindlessly conceding to the supposed light and wisdom that may follow often burdensome and clumsy efforts of assessment overlook, as he remarks, the ways being a “youth in Oakland makes you different from someone who demographically mirrors you.” Or as a wise friend reminded me, a commitment to the local and the up close observations that follow may be the best way to realize genuine mastery.

Duncan-Andrade was profiled in the New York Times’s “Visionaries” series, a continuing feature that profilies, as the description reads, “people from all over the world who are pushing the boundaries of their fields, from science and technology to culture and sports.” Just as I cannot claim the basketball mantle in the ways Duncan-Andrade did, I may be the farthest thing from a visionary you’ll ever meet. For starters, I have spectacularly bad taste in fashion and music, and it seems like those among us who are pushing the boundaries in their respective fields at least should have a sense of how to dress themselves and curate a Spotify account that moves beyond Taylor Swift’s greatest hits. (What can I say? And happy belated 30th, Ms. Swift.)

But despite these hurdles I continue to think about the future of faculty development and what matters about higher education, and perhaps like you,I am not altogether heartened by what I see across the national landscape. And it was the case that I was inspired by something Dr. Duncan-Andrade remarked in his interview. I reproduce it here, altered only slightly: “In the absence of an honest and invested national discourse about the purpose of higher education in a pluralistic, multiracial democracy, we are just playing games.”

I am grateful to teach at Denison, where it is abundantly clear throughout our learning and performance spaces, our athletic fields, academic programs and departments, and offices across the entire college that everyone is invested in our shared mission. We are not playing games here. And I worry that too many of our national conversations about higher education, about what it means and why it matters, amount to little more than playing games. Thankfully, I draw courage from the daily examples of countless colleagues for whom learning and teaching are animating passions; from thinkers who insist that we must argue about the ends of education and embrace the possibilities to be found across a new, uncertain landscape; from friends from far-away places who graciously and tirelessly advocate that bold compassion and tender excellence can share the same space.

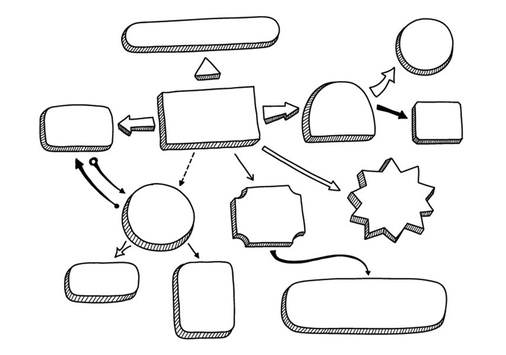

It is both tempting and easy to lampoon visionaries of whatever stripe or consequence, to write them off as supposed cranks or misguided novices.But the truth is far more serious: Visionaries remind us that only by looking bravely into the unknown can we make the world anew. This holds true for public schools in Oakland and it holds true for higher education. The demands on the professoriate, the opportunities and challenges that inflect our efforts to realize genuine conditions for learning, creativity, and intellectual growth, demand that we continue to think creatively and capaciously about the ways faculty are supported across the professional lifespan. We’re at the edge of a new calendar year and now, more than ever, we need to look forward. It’s time to stop playing games. Unless you’re up for some 3-on-3. (Call me?)