It’s easy to feel overwhelmed at mid-semester. There’s so much to do. Grading exams, commenting on papers, determining what course-corrections might ensure students finish well. And then there are the myriad of scholarly and creative projects in which you’re immersed, and the committee work, department meetings, appointments with advisees, search meetings, summative reviews, and supervising student research. It’s a lot.

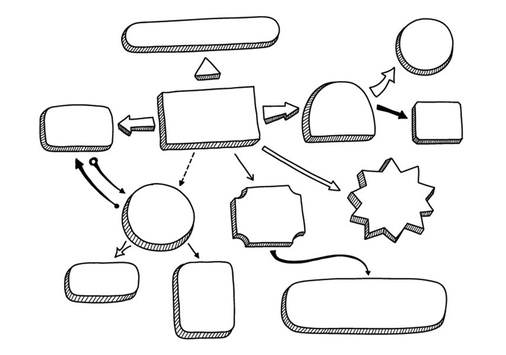

Amidst so much to do, it’s easy to feel lost. How can you find your way through the work-load and recover a sense of balance? I don’t have ready-answers, but I was recently inspired by the lessons of sea-turtles. David Barrie’s illuminating Super-navigators: Exploring the Wonders of How Animals Find Their Way is written with equal parts curiosity, awe, and diligent intellectual effort to answer a deceptively simple question: How do non-human animals find their way around?

The science of animal navigation is complex, and Barrie’s book isn’t exhaustive. But its overarching moral— couched in inviting prose—merits emphasis: As human beings abandon what he terms the basic navigational skills we’ve relied upon for millenia, it remains the fact that countless animal species make their way across arduous terrains in all kinds of conditions and do not get lost. What might we learn from these animals’ navigational skills? How might the lessons of animal navigation help us think about our work as teachers? The sagas of sea turtles offer clues.

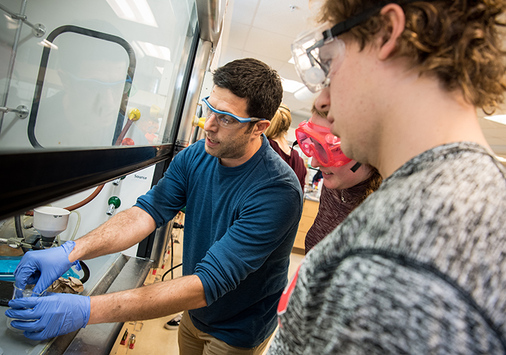

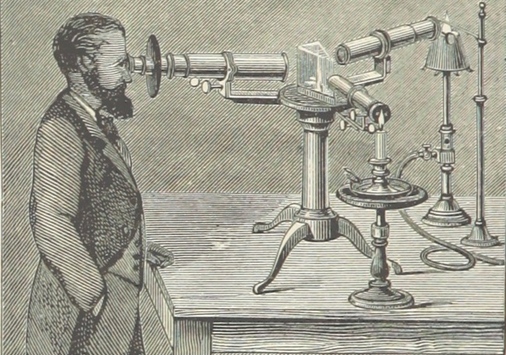

Consider this: Female sea turtles will swim thousands of miles to lay their eggs on the beach where they were born. How do they know where to go without Google maps? Scientists have been tackling this question seriously since the mid-twentieth century. (Okay, scientists don’t mention Google maps.) Ken Lohmann and his colleagues, whose research has appeared in Nature, have studied these animals for decades. They’ve determined that they possess and use magnetic maps.

But that’s not all. Turtles have benefitted from millions of years of natural selection. This evolutionary process seems to have equipped them not merely with internal maps and compasses, but also the ability, as hatchlings, to imprint on what Barrie describes as the “unique geomagnetic signature of the area around their nests.” And olfaction may help them find their way; so too the ability to “read” and hear persistent ocean swells to help them keep their bearings. In short, their navigational abilities are extraordinary.

Another scientist, Paolo Luschi, has a catch-all word for the mysterious ways sea turtles navigate their world—bricolage, the idea of making something from any bits and pieces that may be on hand. As he speculated to Barrie, “turtles [seem to] opportunistically make the best use they can of whatever useful information may be available to them.”

Okay, I know. Sea turtles? Really? What do they have to do with learning and teaching? Three insights come to mind:

1. Use whatever you can to help you find your way through the ocean swells of mid-semester.

Ask your students how the semester is going. Research confirms that asking students about their learning yields fruitful results. At a minimum, the gesture underscores that you see them as partners in the learning process. Along with students’ responses, reflect on your classroom practices; capture these to see what patterns emerge and what these suggest for the remainder of the semester. Invite a colleague to sit-in on a class and give you feedback. It’s easy to think we’re the only ones enduring the swelling waves. The truth is, we’re in this work together. A colleague’s friendly eyes can serve as another bit of information to help you find your way.

2. Pay attention to how you and your students are feeling.

The stress of mid-semester can be brought about by many factors. I won’t pretend to know what you may be juggling in your wonderful, chaotic life. But I know this: the basics matter. Sleep, hydration, exercise, and diet all affect our ability to navigate the ups and downs of our professional lives. Likewise, tune into your emotional well-being. Marc Brackett’s recent book, Permission to Feel, underscores that emotions are a form of information, like news reports from inside our psyches. We can seize on the bits of information our feelings present, figure out what they’re really trying to tell us, and then make the most informed decisions. Paying attention to our bodies and our psyches isn’t easy when we neglect the basics.

3. Just keep swimming.

>No, Dory wasn’t a sea turtle. But the wisdom of the Regal Tang (or its scientific name: Paracanthurus hepatus) merits repeating. Sometimes, the way to find your way is just to keep moving.** The challenges at mid-semester can feel overwhelming, but if you remember to look around and remember your core commitments as a teacher and affirm your students’ genuine curiosity (it’s there, trust me), and strive for class sessions centered on best practices from active learning, meta-cognition, and collaborative reflection, you will not merely survive until the end of the term, you’ll thrive.

Perhaps, finally, we should sit with the insights of Rebecca Solnit, who wrote about search-and-rescue teams in the American wilderness. Barrie drew from her work in reflecting on animal navigation in his chapter, “The Language of the Earth.” Here, in part, is what she wrote:

… a lot of the people who get lost aren’t paying attention when they do so, don’t know what to do when they realize they don’t know how to return, or don’t admit they don’t know. There’ s an art of attending to the weather, to the route you take, to the landmarks along the way… .The lost are often illiterate in this language that is the language of the earth itself, or don’t stop to read it.

Maybe what sea turtles teach us is that finding our way requires most of all that we pay attention. Really pay attention. Good work and balance are just around the corner. Go and search and find them.

**Though here, context is everything. Getting lost in the woods, for instance, is no laughing matter. The U.S. Forest Service strongly recommends hikers adhere to the guidelines embedded in the acronym STOP: Stop, Think, Observe, Plan.