“Taking Students to Prison to Learn about Happiness” by Amy L. Shuster (Philosophy)

Imagine you are the instructor in this classroom: students engaged in personally challenging and open-hearted conversation about difficult texts and complex ideas that require they rethink what they value, and by virtue of that, the way they live. Easy to imagine, right? Now imagine that same conversation where half of the students are incarcerated at a local state prison and half are enrolled at Denison. Last semester I piloted such a course as PHIL 294: The Philosophy of Happiness. My course was inspired by a model developed by The Inside-Out Center at Temple University. Inside-Out is named after its participants: people who are incarcerated are “inside students” and those traditionally enrolled in college are “outside students”. This language names the agency of course participants without ignoring the situation that brings them together in the first place.

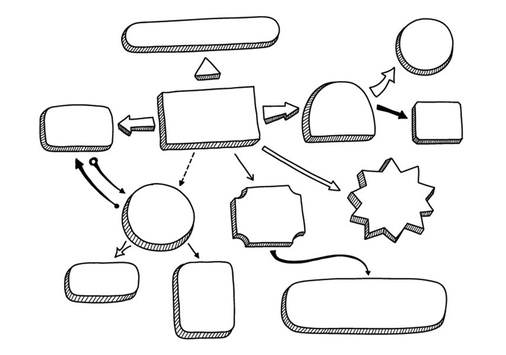

The Inside-Out program provides extensive training and follow-up support to faculty who are interested in offering such courses. This training is especially valuable for faculty like me who lack experience teaching in prison settings and/or who lack sufficient knowledge of the US carceral system. For instance, I learned that residents at the prison where I offered my course are only permitted 2.4 cubic feet of personal items, and their course materials are included in that restriction. While the original Inside-Out curriculum was in criminology, courses from a variety of disciplines are now offered at other institutions in Ohio, around the country and the world (as mapped here). For instance, GLCA colleges—including Albion, Antioch, and the College of Wooster—have offered Inside-Out coursework. And many small liberal arts colleges participate, including Amherst, Bowdoin, Bucknell, Haverford, Mount Holyoke, Pomona, Smith, Swarthmore, Vassar, Washington and Lee, and Williams. Therefore, Denison’s pilot is in line with an established practice of offering similar curricular experiences to students.

“How is this course not just tourism?” So asked an outside student early in the semester. In the first few weeks, it was hard not to feel this way. Outside students drove 45 minutes to the prison, and then at the end of class they drove back to campus. Class was held in the prison’s visiting hall, outside students were admitted into the prison under a “volunteer” status, and inside students came to class in their prison uniforms.

The question about tourism implied a critique, one that was grasping for the course’s deep features. Tourism involves a one-way cultural exchange. By the end of the semester, inside and outside students realized the two-way exchange that animates the heart of the Inside-Out model. In particular, we recreated the liberal arts classroom—including practices of slow, close reading and at times heated disagreement about the interpretation, application, or significance of the ideas on offer in the course.

And characteristic of genuine exchange, each culture was inevitably transformed.

In prison culture incarcerated people are only referred to by “inmate”, number, or last name but in our liberal arts classroom only first names were used. Ever since Pell grant funding was cut for college in prison programs in the 1994 crime bill, educational opportunities in Ohio prisons offered through the Ohio Penal Education Consortium (OPEC) are limited to people who are no more than five years to the street and to courses that offer vocational training. My course was one of only a few programs at the prison that did not similarly restrict access to people and ideas. Inside students reported that class was the one time each week when they felt free: they could pursue their malnourished desire for knowledge and intellectual exchange amid a community that respected each one’s contribution to discussion. Inside students completed their reading assignments amid the persistent noise of their housing unit and shared what they were learning with a bunkmate when they are otherwise forbidden to exchange possessions. Comparing their engagement with the course material with that of the outside students reinforced or planted the belief that they are indeed college material.

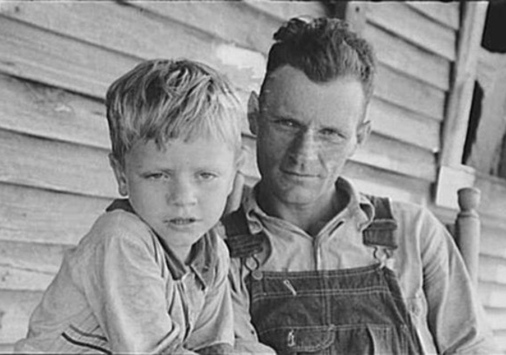

In liberal arts culture students can try on an idea in class and then leave it there but, when the site of learning is carceral, the need to redesign private lives and public institutions in light of what they carry away from class each week became urgent and unavoidable. The divide between “the ivory tower” and “the real world” became at once more and less palpable. In my early conversations with outside students who expressed interest in the course, I asked them to tell me a little about their experiences with smart men of color who are at least 20 years older than them and from poor or working-class backgrounds. Most were stumped; one named the doorman in their building at home. These reactions are not unique to Denison students, but rather a product of the communities that American college students come from. For the outside students, the course not only undermined tired stereotypes of people who are incarcerated and life “behind bars”—including the availability of happiness in such a context—but also expanded their experience of race, class, gender, age and intellectual capacity. Outside students reported that they were surprised by how much they came to value the opportunity to learn alongside people who are incarcerated. This course offered a unique opportunity for improbable but necessary encounters across differences that too often are ignored.

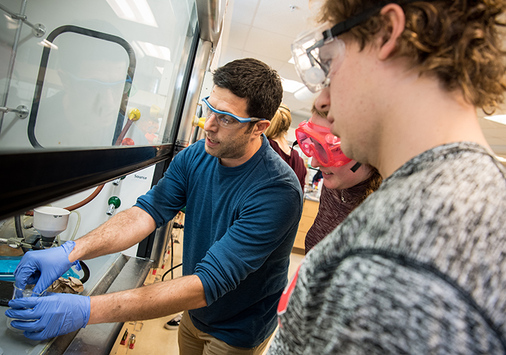

As I have grown as a teacher, I find myself increasingly more uncomfortable with the “sage on the stage” model of learning and experimented with more active modes of learning. The Inside-Out model thematizes its theory of learning in terms of a shift from pedagogy (which, as its root suggests, focuses on education for children) to androgogy, or better, anthrogogy (i.e. education for humanity). Instead of lecture, Inside-Out recommends highly choreographed small group discussions and class activities that demand students apply course material to real-life situations and concerns. Assignments require not merely an intellectual consideration of the course material but also trying them out in practice—and assessing the intellectual value of those ideas in light of that practical experience. As a consequence of this design, learning in my course was not merely intellectual, but practical and embodied. In other words, learning was not merely active but experiential—this permitted my students to become not only better students, but better persons.

A goal of the course is building an engaged intellectual community in an unlikely circumstance. The desired community can only be achieved through repeated face-to-face interactions in close quarters that focus on naming, exploring and—where possible—solving shared problems and concerns. To this end, the Inside-Out model recommends 12 weeks of instruction in a common in-person classroom, 3 weeks of instruction in separate classrooms to process the common experience (in the first, third, and final weeks of the semester), a group-project that is carried out over multiple weeks, and a closing ceremony where honored guests (including family, friends, administrators, and community-members) witness groups present their projects and each participant is formally recognized for their achievement in the course. I discovered the value and necessity of each of these features in the process of piloting the course.

The course’s theme—philosophies of happiness—was predictably inflected by the learning environment. One surprising outcome was that inside and outside students alike traded hedonist and desire satisfaction theories of happiness for accounts inspired by Buddhism and Aristotelianism. Another surprising outcome was that both sets of students began to see how negative affect (like discomfort) and negative states (like failure) might be part and parcel of a happy life.

At the closing ceremony, one student offered the following reflection on the experience: “In four years, I have not found a course that better embodies [Denison’s] mission than the Inside-Out model. As much as I value the liberal arts classroom experience, it is often an insular one that leaves students unsure as to how their newfound knowledge relates to the ‘real world’. This class provides exactly that application of knowledge in the real world. How do you talk about something like the philosophy of happiness knowing that you are learning in a fundamentally unhappy place? How do we find a place where academia intersects with practicality and how do we teach abstract, even indulgent subjects in a way that also recognizes the real struggles and realities of our classmates? This type of education is, at least to me, the true mark of a great liberal arts institution, and the values it instills are the true mark of a liberally educated citizen.”

The pilot offering was not without its flaws. For instance, inside students did not earn academic credit for completing the course. The opportunity for college credit creates real incentives for inside students to pursue higher education. And yet inside students were expected to do all the same work as outside students but without the material step towards a degree at the end. This lack of equity undermined the quality of the class experience as both populations did not have the same thing on the line. Moreover, outside students would not receive this distinctive and impactful educational opportunity without the participation of inside students. Rewarding credit is one way of recognizing the work of inside students on these two fronts. Over the summer I interviewed professors and registrars at other small liberal arts colleges around the country to learn how they make transcript credit a possibility for inside students. As a result, I am drafting a proposal for Denison to consider extending credit to inside students in the future. Issuing credit to inside students would disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline and lay the groundwork for a prison-to-college pathway that should characterize just communities.

The Inside-Out model calls attention to how the walls built to keep people in also function to keep people and needed resources out. I am satisfied by the idea that access to education is an inalienable human right, that life-long learning is an expression of our humanity. To family, friends, neighbors and colleagues who need more, I offer that almost everyone who is incarcerated in Ohio will get out in their natural lifetime. Our current punitive system does not empower restored citizens to add value to, let alone express their care for, the communities to which they inevitably return. We can and must do better.

I am grateful for the opportunity to offer the course and for the support it received from the Office of the Provost, the Alford Community Leadership and Involvement Center, the Center for Learning and Teaching, the Lisska Center for Scholarly Engagement, and especially the Department of Philosophy. The course was made possible by a statewide partnership between the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (ODRC) and Inside-Out to grow course offerings in methodical ways. In particular, Dr. Angela Bryant (OSU Sociology) generously mentored me in the design and implementation of my course. Last but not least, this course would not have been successful without the courageous interest and extraordinary commitment of the students—both inside and out—who enrolled in the course.

I hope this account inspires other faculty on our campus to develop courses on the Inside-Out model.