First, a confession: I watched a lot of television this summer.

Tops on the list was Friday Night Lights. (Don’t judge—it was my summer. And yes, I have read the book that inspired the series.) But the most moving television was two documentaries about rock climbing and the sagas of Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell, respectively. Now, to be clear: I don’t pretend to understand the lingo or the culture or the technical gear of rock climbing. But watching Free Solo and The Dawn Wall changed my life. Well, not quite. But both documentaries, in addition to being beautifully filmed and beautifully raw in their fundamental premises, illuminated profound lessons every climber should remember. Teachers should bear them in mind too. Interestingly, they amplify the year-long theme for the Center for Learning and Teaching: Resilience. Curious? Read on.

Everything begins in the body. I will never do as many pull-ups as Honnold or Caldwell, the films’ protagonists. The larger lesson is this: Both climbers were keenly sensitive to all aspects of their physicality, the ways they moved on El Capitan (yes), but also how they walked, stood, sat, and napped. Their bodies cued them to the wider rhythms and pulses of the world. Their bodies felt (fear, excitement, panic) before emotions registered those feelings. What does this have to do with teaching? How I sit, stand, listen, and talk with my students—how my body attunes to the learning unfolding in a class—makes all the difference. Students are watching, and they will take cues from what we project. Lead with your body, and listen to it.

Attitude is everything. Rock climbing is hard. And fraught with risk. There are countless reasons not to try it. Yet Honnold and Caldwell displayed something like a ceaseless, unadulterated joy, even in the throes of uncertainty, fear, and doubt. Both climbers recognized that how they thought about something made it so. What does this have to do with teaching? The attitude we bring to a class or an assignment or an office-hours conference is contagious. Students will graft onto your attitude about learning. What do you hope for them?

Control what you can control. Rock climbing demands total preparation. Both Honnold and Caldwell trained for and visualized the routes that would lead them up El Captain. Preparation was essential and there were no short-cuts; they practiced relentlessly. And then the wind kicked up or rocks fell on their heads or the temperature dropped to bitter-cold levels. Knowing what they could control and moving gracefully through the uncertainty of what they could not helped them be responsive, flexible, and balanced, on-and-off the rock face. What does this have to do with teaching? Prepare to give your students your very best. And know that things will not go as you planned. And that’s okay.

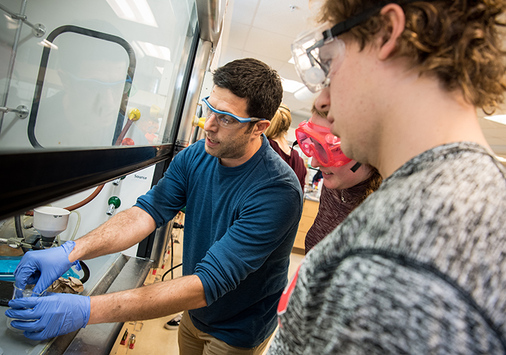

Ask for help. It’s tempting to see Honnold and Caldwell as super-individuals, alone on the rock face courageously finding the edge that will hold their weight and propel them upwards. But no one climbs alone. Ever. Both men understood the need for partners (on the rock face and off), for a community of like-minded souls who believed passionately in the values and habits that drove them to try the impossible. What does this have to do with teaching? When we close the doors to our labs, studios, or classrooms, we might feel, even in the midst of our students, curiously alone. When a discussion falls flat or an assignment spurs more frustration than enlightenment, we may think we must work through these setbacks alone. But help is all around. You just have to ask.

Taken together, these qualities gesture to resilience, a collection of practices and beliefs predicated on the idea that, in the throes of difficulty, we can bounce back. Such a posture doesn’t hinge on a Pollyanna attitude but on a realistic assessment of one’s circumstances, coupled with mining resources and cultivating relationships that will enable you to recover and rise again.

There are other ways to think about resilience—what it means and why it matters—and I’ll write more in future Director’s Cuts. For now, this: the work we do is hard. Amidst the excitement of the first weeks of the semester, it’s easy to overlook the obstacles that will arise. A commitment to something like a resilient pedagogy—for ourselves and for our students—might equip us to work through the hurdles that will get in our way. Interested to learn more? Let’s talk.

A second confession: I intended to confine this essay to all things rock climbing and resilience. And then “Send them back!” happened. And then El Paso. And then Dayton. Writing about rock climbing and pedagogy and resilience seemed trivial.

That confession, in fuller relief: When I started teaching at Denison, I believed if I was a subject-matter expert and dedicated myself to grasping the basics of effective teaching, I could realize a career inflected by the highest ideals of the liberal arts and the culture of the university. But now I have come to believe this: Standing pat as a content-expert no longer is enough. Our students heard those chants and felt the tremors of that gunfire in two U.S. cities. Something more is needed.

I hope you will see the Center as a place of unflagging support for your professional development. We are tasked to do so much in service to a great mission. And those tasks, that mission, are not insulated from the chanting or the gunfire or absurd vitriol masking as political leadership. And maybe that’s the rub: What all of us do here, every day, matters profoundly to the formative development of young adults and the aims of liberal education. Maybe such work has never mattered more.