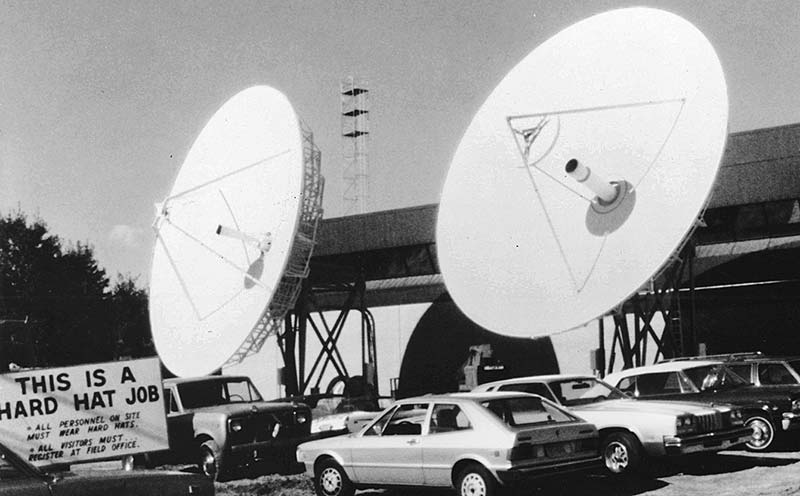

ESPN is headquartered in Bristol, Conn. When the network began, its campus was a series of trailers and sparse sets.

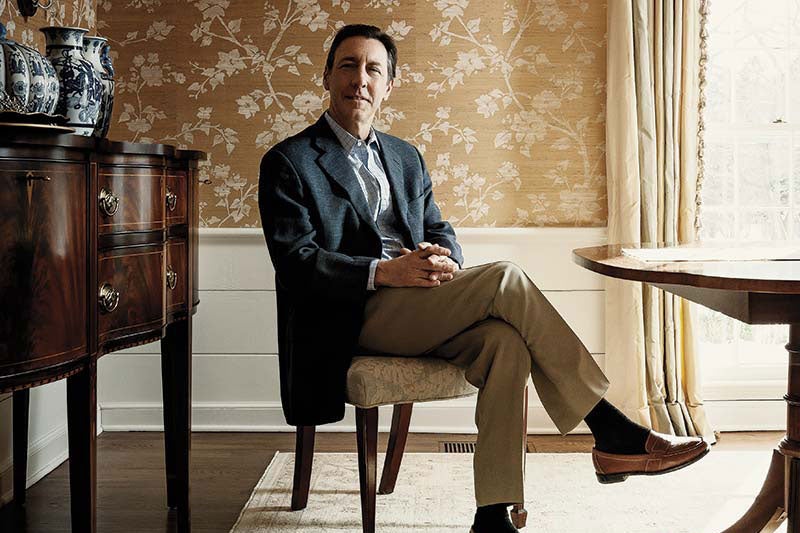

It was a bright, frigid Friday in February, and George Bodenheimer was back in the comfortable study of his home in New Canaan, Conn. The day before, Bodenheimer, the former president and executive chairman of ESPN, made the hour-long drive to the company’s headquarters in Bristol to attend a memorial service for Stuart Scott, the popular, longtime ESPN personality who died in January after a long battle with cancer. The sadness of the occasion was tempered slightly by memories of Scott’s relentless positivity, and by the chance to reconvene the network family. For Bodenheimer that idea of an extended corporate clan is arguably the proudest legacy of his 33-year career at the company.

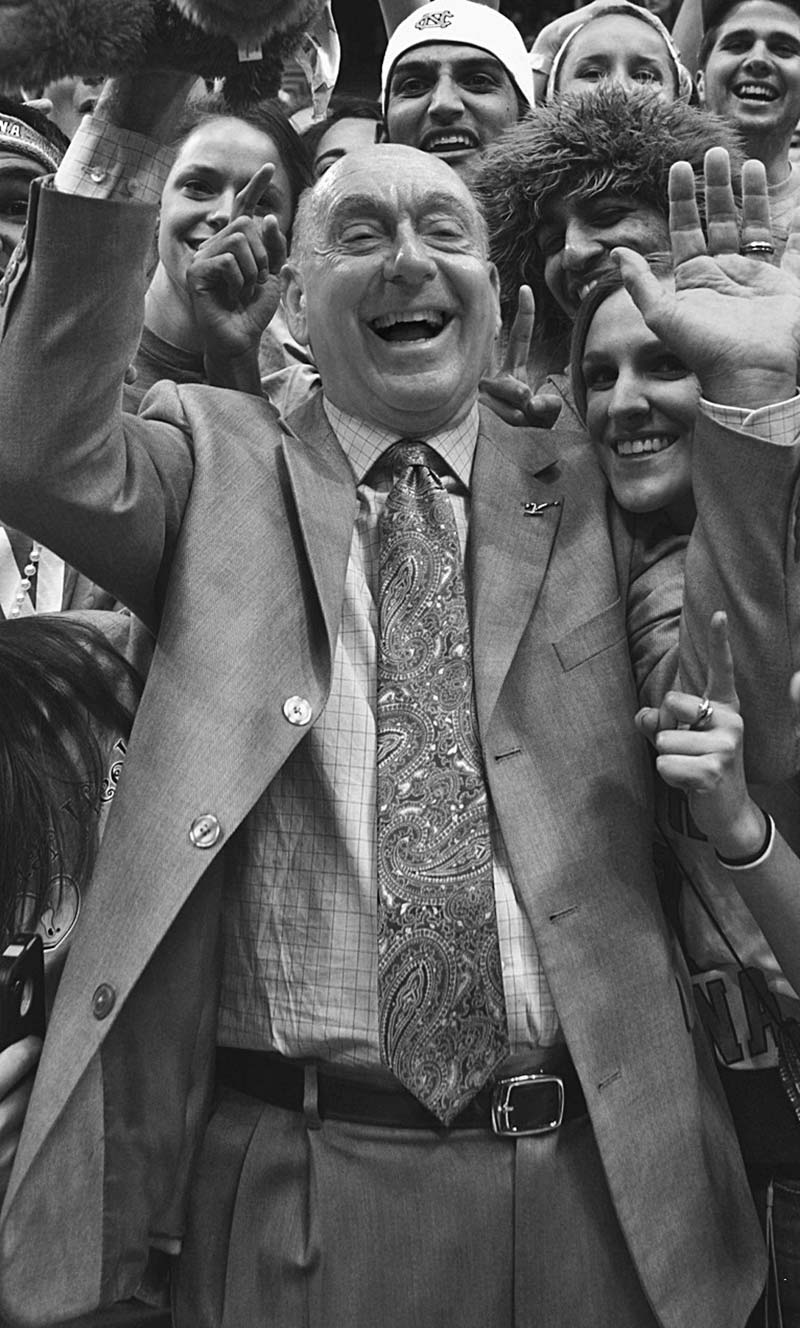

This May, Bodenheimer will receive the lifetime achievement award for Sports from the National academy of Television arts and Sciences. That same month, Bodenheimer’s book, Every Town is a Sports Town, will be released. It details his rise from mailroom attendant, gopher, and occasional airport-shuttle driver (Dick Vitale was a regular pickup) at an upstart cable network to president of a global sports media conglomerate. Part memoir, part leadership guide, it’s a project that coincides with a busy retirement: In addition to several corporate boards, Bodenheimer sits on Denison’s board of trustees. another cause close to his heart is The V Foundation for Cancer research, founded by ESPN and the late North Carolina State coach Jim Valvano. all of Bodenheimer’s proceeds from the book will go to The V Foundation.

Bodenheimer retired last May, but when we caught up with him in February, it was clear how much he still feels a part of the network. We spoke about ESPN’s remarkable growth, the lessons he learned along the way, the importance of listening to your employees, and what the future holds for the “Worldwide leader in Sports.”

As you write in the book, you took an unglamorous, low-paying job in 1981 at a company most people hadn’t heard of. Have you ever thought about what you would have ended up doing if you’d passed on ESPN?

(Laughs) I never really thought about the what-ifs. I knew I wanted to be in something in sports or entertainment. I wanted to go work at Madison Square Garden. The Knicks one night, the Rangers the next, the Rolling Stones the next night, throw in a big political convention, the circus—how great could this be? I went to the employment office there, and I couldn’t even get an application.

But at ESPN, I never really thought about leaving. People ask me all the time, “Gee, you spent 33 years with one company, what’s the matter with you?” I had a wonderful experience there, and obviously I was lucky and able to get in with a company that has never stopped growing.

I’m guessing that had something to do with why you never left—there were always new opportunities and new challenges.

It never got boring.

Do you think a story like yours can still happen? The idea of starting on the bottom rung and rising to run a massive company?

I’m an optimist. Is it the same as it was 50 years ago, 35 years ago? No, things change. But I certainly do believe there’s opportunity. People always ask me, “Well, how did you do it?” I was willing to work hard, and I learned early on—which was some of the best advice I ever received—to become a student of the business. If you just go to work every day and do your job, and watch the clock, and get out of there as soon as you can, you’re not going anywhere. But if you have the discipline to be a student of your business, that shows. It takes work. You can’t mail it in. I think for young people today, particularly those coming out of a fine school like Denison, if you’re willing to put the work in, and you’re a student of the business, you have as good a shot now of rising up at any company as you did 35 years ago.

There are some great anecdotes in the book from ESPN’s early days: the ubiquity of Australian Rules football matches, college kids stealing the ESPN banners at games. There was a hipness to the network then. Were you aware of how cool it had become?

Not really, but in the beginning, we were like, “Holy cow. They’re stealing our banners?” When our trucks would pull into a town to do an event, it became an event on the college campuses: “ESPN’s here.” We saw that starting in the early ’80s. And it was very organic. Over time we got more sophisticated with the marketing, but early on, we were making it up as we went along. In the book, I use the example of Aussie Rules football. We put up a graphic on the screen, and we said, “If you’d like a copy of this rule book, send us a postcard.” That was 1981. We got 10,000 postcards. And I was in the mailroom, so I know this. That was long before we had ratings, so that was like a tangible: Wow, there are 10,000 people who want a rulebook for Aussie Rules football? There are fans out there enjoying what we’re doing.

It All Started in the Mailroom

As he recounts in the opening chapter of Every Town is a Sports Town, George Bodenheimer’s job interview at ESPN lasted all of two minutes. The HR director at the upstart cable network told Bodenheimer he was qualified for a position as a “mailroom guy,” a job that included delivering mail around the company complex, shuttling visitors to and from the airport, and occasionally shoveling snow. Shortly after graduating from Denison, Bodenheimer took the leap of faith, signing up for a starting annual salary of $8,300 in 1981; among his duties was serving as the regular driver for an excitable, recently fired basketball coach-turned-announcer named Dick Vitale.

From that humble start, Bodenheimer had a front-row seat for three decades of drastic changes in sports: how the games are watched and reported on, the higher profile (and even higher salaries) of modern athletes, and the staggering costs and profits for those who own the teams, run the leagues, and secure the rights to broadcast the games. ESPN has been central to that evolution, and in a 13-year stint as the network’s president, Bodenheimer played an indelible role in expanding the network’s influence. Here, a look at some of the most memorable moments from his and ESPN’s shared history.

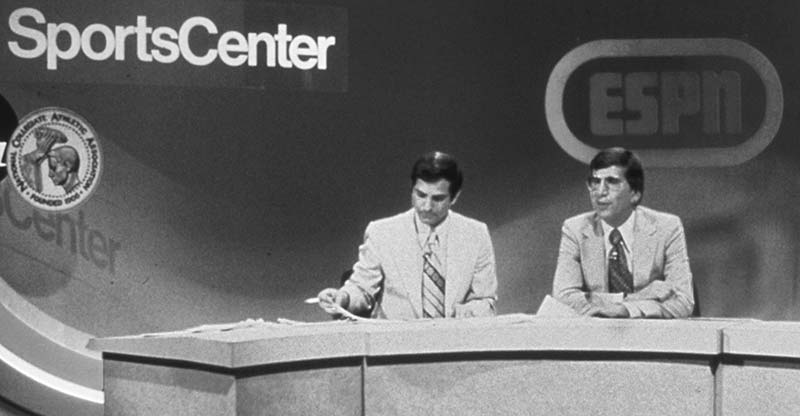

September 7, 1979 ESPN premieres with the first episode of SportsCenter.

1981 Bodenheimer accepts a position in the network’s mailroom.

1984 ABC acquires the network for approximately $200 million.

1985 Bodenheimer becomes national accounts manager at ESPN. He is stationed in Denver, Colo.

1989 Bodenheimer becomes a vice president, and heads back to ESPN headquarters in Bristol, Conn.

1992 The ESPN Radio network debuts on 170 stations across the country. It now has more than 500 affiliates.

1993 The network expands with the launch of ESPN2, aka “The Deuce,” which is marketed as a hipper sister channel.

1993 ESPN helps establish The V Foundation for Cancer Research, named in honor of former North Carolina State basketball coach Jim Valvano, who dies that year after a battle with cancer.

1995 Looking to capitalize on the growing popularity of extreme sports, ESPN broadcasts the first X Games.

1995 The network goes online with ESPNET SportsZone; eventually, its web presence is rechristened ESPN.com.

1996 The Walt Disney Company buys ABC, giving it an 80 percent ownership stake in ESPN; Bodenheimer is named executive vice president, sales and marketing, of ESPN.

1998 ESPN The Magazine is launched to challenge the industry dominance of Sports Illustrated. Bodenheimer is named president of ESPN.

2000 A Portuguese language version of SportsCenter, broadcast in Brazil, is the show’s first international edition.

2002 ESPN becomes the first network to have broadcast rights to the four traditional major North American sports—the NFL, NHL, MLB, and NBA.

2004 In addition to his presidential duties, Bodenheimer assumes the role of co-chair, Disney Media Networks.

2005 ESPNU is launched with a focus on 24-hour coverage of college sports.

2006 The venerable Monday Night Football broadcast, aired on ABC since its 1970 debut, finds a new home on ESPN.

2007 The launch of ESPN360.com (now known as ESPN3) allows viewers to stream live sports over the Internet.

2009 The network marks its 30th anniversary with the debut of “30 for 30,” a series of critically acclaimed sports documentaries.

2010 In a nod to the growing interest in international sports, ESPN broadcasts soccer’s World Cup for the first time.

2011 The network reaches 100 million U.S. homes.

2012 Bodenheimer assumes the newly created role of executive chairman of ESPN, Inc., ceding the presidency to longtime ESPN executive John Skipper.

2014 In May, Bodenheimer retires after 33 years with the network.

2015 The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences awards Bodenheimer a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 36th annual Sports Emmy Awards.

“Most fans don’t have 18 hours a day to devote to the NBA or NASCAR or hockey. So they listen to the guys who do.”

In the beginning, you write, it was unknown if fans would watch the NFL draft, and yet it brought huge ratings hits. Were there events that stand out from your career in which you knew that ESPN coverage would mean people would watch them?

I think of the early rounds of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament in the ’80s. We would get calls from firehouses, fraternities, people saying, “Hey, we’re going to skip school today. We live in Tulsa. Where’s the nearest bar that gets ESPN?” We used to get those all the time, for the draft and for the NCAA. So I think that’s a real tangible example where we could see, hey, these events are changing patterns. And there’s SportsCenter. If you’re a fan, you want to see a half-hour or 60 minutes of sports highlights, any night of the week. Tune in at 11, tune in at 2:30 a.m., shift workers getting home from work—that’s why we started showing it in the morning. I think SportsCenter had a major impact on the viewing of sports news in this country. I know that sounds like a very obvious statement, but that just didn’t exist in ’79. SportsCenter probably did more to change the practice of sports fans’ viewing than anything.

You traveled a great deal, especially when you were on the sales side earlier in your time at ESPN. How important was that in your development and approach to business?

That’s the derivation of the title of the book. Traveling around, particularly in the Southwest, I got more of a feel for the importance that sports play in the fabric of the country. I was told, time after time, “You know, George, this is a sports town.” And it really was interesting, and it also gave me a great deal of confidence that ESPN was going to be a success.

One of the criticisms of the network in recent years is that ESPN’s close relationship with the leagues it broadcasts might prevent it from objectively covering those leagues. It’s a fine line to walk. How well do you think ESPN has managed that?

I think very well. ESPN tells it like it is, regardless of the story or subject matter. That’s an important part of what SportsCenter is, and an important part of what ESPN is, and I think sports fans know that. Believe me, I was the guy who took those calls for 13 years. It’s anything but, “Oh, let’s only report the good news.” We’re reporting sports news—good, bad, or indifferent. We’ve managed that by having a wall between our editorial operations and the management of the company. I was never telling SportsCenter, “Here’s how I’d like to see this story covered,” and never would. The day that starts happening is not a good day for our company. And the fans would see that, too.

Were there times that were difficult, because of the partnerships ESPN had?

Sure. And when I got the calls, I would always say three things: Did we get the facts right? Did we give you a chance to air your point of view? And this was more internal, but I didn’t want anybody making it personal: This is business. But if you have an opinion about an issue with sports, and you’re on our air, then you’re more than welcome to air that opinion. That was it.

One of ESPN’s recent mottoes has been “Embrace Debate.” That opinion-based programming has become a huge part of what’s on air. When did you see that that was going to be such a driver for the network?

We turned to that in the early 2000s. In that era, when we were really thinking about how to increase ratings, we developed the EOE business, ESPN Original Entertainment, and we started producing made-for-television films. That’s when Around the Horn and Pardon the Interruption [ESPN talk shows] were developed. And we were infusing SportsCenter with more opinion and commentary, as a very definite strategy. I think it’s been validated. Most fans don’t have 18 hours a day to devote to the NBA or NASCAR or hockey. So they listen to the guys who do. As a result, fans are better informed. I think it’s a service to them.

At some point ESPN became what you describe as a “global sports media company.” What surprised you about the ways in which people embrace sports in South America or Europe, versus how we do that here?

The greatest lesson was that typical American thinking, “We’ll send them what Americans like, and they’ll enjoy it.” Not really the case. The real meat and potatoes is what they favor in those countries. It took us a while to figure that out. I know that sounds painfully obvious now, but it wasn’t painfully obvious, at least to us, 20 years ago when we were just getting started.

The reverse has also been true: Some global sports, particularly soccer, are increasingly popular in the U.S. ESPN’s coverage, particularly of the last two World Cups, has played a big part in that.

We’re very proud of that. It’s become a big event in the United States, and I think ESPN has played a big role in that. ESPN has always been an innovative company, and again, while it doesn’t seem like innovation now, 10, 12 years ago, you could argue that it was certainly innovative to program European football in the United States.

Sports now permeate mainstream culture—athletes are involved in Hollywood or the music industry, TMZ has its own sports gossip site. Did you see that coming?

I’ve got to go back to the real growth of SportsCenter—when it became more than coverage of runs, hits, and errors, to covering the personal lives of athletes. That begat more commentary, and that begat ESPN the Magazine, trying to forge a different identity from Sports Illustrated—what athletes wear, listen to, the celebrity of athletes. So yes, I think we knew that was happening, and our actions fueled that.

You write that ESPN felt like a family in those early days. Do you think you were able to maintain that to some extent? And if so, how did you pull it off?

When I became president in 1998 after being with the company for 17 years, I studied for my first company-wide address. I could have recited our projected growth rate for any of our business units worldwide. So I deliver this painfully long address, and I open it up for questions: “Hey George, can we expand the hours of the fitness center?” “Hey George, have you been in the parking lot after dark recently? Do you see how dark it is out there?” “Hey George, why does the cafeteria still use Styrofoam? Don’t you know that’s bad for the environment?” Those were the first three questions, which of course I didn’t have any good answers for, because I was studying the growth rate in Europe. But boy, did that teach me a lesson: that as a leader, as a CEO, you better pay attention to what’s on the minds of your people. That’s one of the best lessons I ever received. It really influenced how I acted as president for 13 years. You take care of your people, they come through for the company. The memorial for Stuart Scott was in our childcare center. It’s a beautiful facility, opened three years ago, and it was by far the most requested item of our employees. When we would survey them, they’d say “We need help with day care.” Well, this isn’t rocket science. And it’s a wonderful success. So, have a nice fitness center, have a nice cafeteria with good food. I put my emphasis on our people. I tried to know as many as I could. That meant a tremendous amount of handwritten notes, employee gatherings, walking around the cafeteria, being visible; anytime I went to an event, I didn’t just head up to a suite, I got around and shook hands with the crew, religiously. And in talking about the company, I talked about the people and the culture and the mission as much as, if not more so than, the business. Sometimes people ask more cynical versions of that question: “What does that mean to be a family-oriented company when you have 7,000 employees?” And my answer is, we care about our people.

ESPN has essentially never stopped growing. Was there ever any concern that the network could, on some level, get too big for its own good?

Well, I don’t know. If someone wants to discuss this in the abstract? Of course. But I never accepted “We’re getting big” as an excuse for anything. I would hear, “Oh, problem X, well that’s because we’re much bigger than we used to be.” Well, look at the Disney Company, or IBM, or General Motors—they’re big. We’re still a peanut. So I never accepted that as an excuse for anything. I think it comes down to the management, and I think bigness in and of itself is not a bad thing.

Dealing with talent: ESPN has had some very well-known personalities, sometimes mercurial, often being wooed by competitors. How did you deal with situations like that? I’m a really straightforward person. I’ll meet with you, and we’ll discuss what the issues are, and I’ll try to be reasonable and discuss a solution. But if you want to leave because somebody wants to pay you X amount more, then you should leave. I hope you stay, but I used to say, we don’t lock anybody in. And if you don’t want to be here, thanks for your service, but I guess we’ll have to learn how to live without you. And I don’t really believe anybody, whether it’s the most high-profile talent or the president of the company, is bigger than the company itself. And frankly, the performance of the company bears that out. So I didn’t find that to be too difficult. I also think a bit of my mailroom sensibility—working my way up through the company—crept in at times like that … a lot of folks ought to take a step back and count their blessings.

What are the biggest challenges facing the company going forward?

One, this has always been about sports fans. The mission of the company is to serve sports fans, anytime, anywhere. And that statement is simple, but executing it is anything but. Number two is financial. The prices of broadcast rights continue to rise, and that’s a challenge. People have always asked me, “How much higher are the prices going to go? When is this going to stop?” And I don’t have an answer to that. The business is so competitive, and live sporting events are turning out to be some of the most valuable content that exists. So managing that from a business perspective is certainly a challenge. I believe that the culture is the No. 1 thing for any company or organization. I think ESPN’s culture is the strategic advantage of the company, based on risk taking, innovation, integrity, family. Those are the hallmarks. Contracts are going to come and go, technology’s going to change, fans’ tastes may change, but if ESPN keeps doing what it can to serve the fans, it will continue to be successful.

I’ve spent the better part of 20 years in and around sports media, and I can’t watch a game without thinking of what goes on behind the scenes. You know better than anyone how the sausage is made—are you able to just turn on a game, sit back, and enjoy it as a fan?

Yes. I’m fortunate because my family is made up of big sports fans. My wife, Ann, and kids [including George Bodenheimer Jr. ’12], we watch a lot of sports as a family. My wife’s a huge football fan—the Giants and Penn State. Now, they give me a hard time, because they claim I can’t sit down and watch anything without reading something as well. But it’s much easier now that I’m out of the company. When I was there, I was thinking about contractual relationships, who’s on the air, etc.—you’ve got all that swirling around in your head. So it’s a lot easier now.

Lastly, the College GameDay traveling circus that visits a different school each weekend during football season is an ESPN institution at this point. It usually ends up at an SEC or Big Ten game, but I have to ask: Were you ever tempted to send GameDay to Granville?

You know, that’s probably my biggest regret. (He laughs.) We should’ve done that.

–Ryan Jones is a senior editor at The Penn Stater magazine and the former editor-in-chief of SLAM Magazine. He is the author of King James: Believe the Hype: The LeBron James Story.