There isn’t anything particularly special about the room of Spencer Greene ’14. A bag of golf clubs is wedged between his bed and mini-fridge; a poster of the periodic table covers the opposite wall; two avocados and a vanilla candle sit on his desk; and books ranging from Game of Thrones to Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Death by Black Hole line the shelves. A boy lives here, and it could be any boy. However, a constant reminder of the difference between Spencer and everyone else living in Sunset House on Denison’s campus lies in the corner of his room, in the white FedEx box next to the bed.

“Nearly 70,000 new cases of primary brain tumors will be diagnosed in the United States this year. Of those, approximately 1,400 will be oligos.”

Underneath its layers of cardboard and plastic lie two small, inconspicuous turquoise pills. They are his final doses of CCNU, an anticancer chemotherapy drug he has been taking for close to a year.

“I’m so excited. Seriously,” says Spencer, smiling as he cups the capsules in his hand. “I won’t be feeling great for the next couple of days, but at the same time, I will, because I know that I don’t have to go through this again. At least not in the near future. This is the pinnacle of my last six years.”

It’s close to 10 p.m. when Spencer takes the medication with a gulp of water.

“It’s really anticlimactic,” admits the psychology major from San Anselmo, Calif. “I’ll probably wake up in the middle of the night feeling really nauseated, but usually I’ll just drink some water and fall back to sleep. Then I’ll go to class in the morning.”

As his ritual demonstrates, balancing college and cancer is not something new for Spencer, who was diagnosed with an incurable oligodendroglioma (or oligo) brain tumor right before his senior year at Sir Francis Drake High School.

Since that initial diagnosis in 2008, Spencer has had two surgeries, six weeks of radiation, 30 rounds of chemotherapy, and almost 130 individual doses of various chemo drugs. During his four years on campus, his Denison room has frequently doubled as a hospital.

But his life continues to move forward despite his diagnosis, and Spencer is left with a choice: to seek fear or bravery, depression or optimism, control or chaos.

Oligos develop from oligodendrocytes, a type of cell within glial tissue, which supplies support and protection for neurons in the brain. The tumors can be found anywhere within the brain’s outer layer, but are most commonly discovered in the frontal lobe, which controls emotions, decision making, problem solving, behaviors, and consciousness. They also can affect the temporal lobe, which regulates memory, emotions, hearing, language, and learning. So oligo sufferers not only face seizures and headaches, but the very core of who they are can be altered by personality changes and learning difficulties. These tumors grow slowly, a blessing certainly, but their slow growth, varying locales, and generalized symptoms also make them difficult to diagnose. Oligos, in so many ways, are a mystery.

In Spencer’s case, the symptoms seemed to appear out of nowhere during a soccer tournament. “It was two minutes into the game, and I was in this weird fog. If you’ve seen Inception, it was like when the ground comes up and becomes the sky. It was a spatial disorientation.” Then his right arm started seizing.

I realized we just had to change the future.

The moment passed, however, and nothing seemed particularly concerning until he had another focal seizure in his arm a couple of weeks later when he was with his parents, Brock Greene and Pam Baskin. “Before it happened in front of my parents, I thought maybe I had something weird in my system that day. But I was sitting there and couldn’t take my hand off the chair arm. That’s when we decided to seek medical attention,” says Spencer.

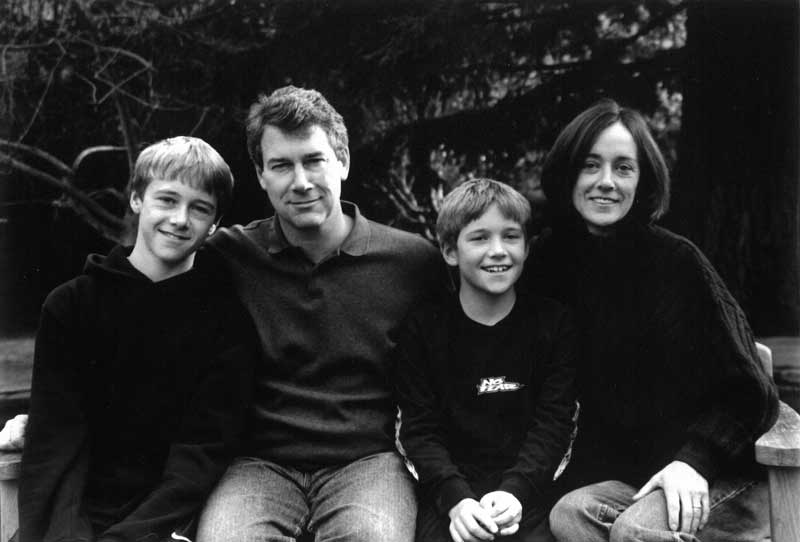

On Friday, August 1, 2008, Spencer got an MRI, the last test after a slew of inconclusive exams. “I think we all remember that day crystal clear,” says Brock. “Spencer, Pam, and I were all waiting in the E.R., and the doctor eventually came in and told us that Spencer had a mass on his left frontal lobe.”

Spencer had only one question: Will I live? “All the doctor said was ‘I don’t know,’ and then he left,” says Spencer. The diagnosis and the doctor’s bedside manner left the family reeling. “It was almost worth being in a comedy. That’s how egregious it was.” Five days later, Spencer headed into surgery to have the lemon-size mass removed.

Time passed. Hope grew. Spencer graduated from high school and weaned himself off the antiseizure medication during his year-long stint as a volunteer for City Year Los Angeles. City Year is a national organization that works to increase education and graduation rates in high-poverty areas. Then, less than a year after his surgery, the seizures came back. “You don’t know the whole score when you set out,” says Brock. “It unfolds with time.”

Spencer and his parents made the decision to start chemo as they gradually learned that Spencer would never be cured. Doctors could cut it out. They could try to shrink the mass with medication. But they couldn’t eradicate it; they didn’t know how. Spencer would never be completely cured.

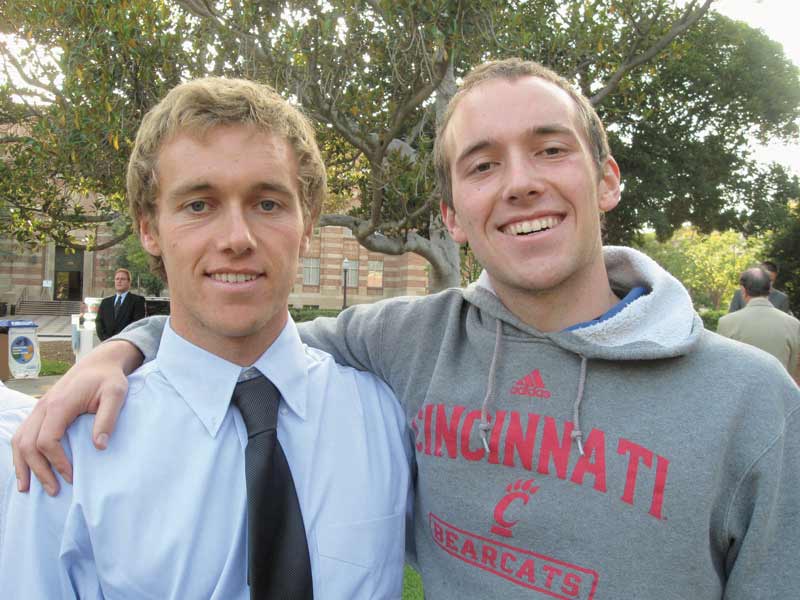

Soon after Spencer decided to begin chemo, Zach, his older brother by 30 months, had a grand mal seizure during a family vacation in Mexico. He was diagnosed soon after with the same incurable tumor as Spencer. It was another devastating blow to the family, and one that left doctors scratching their heads.

The American Brain Tumor Association reports that only 5 to 10 percent of all cancer is hereditary, and there is no history of brain tumors on either side of the Greene family. Even the genetic investigation done on the two boys by a geneticist at the University of California-San Francisco was inconclusive, leaving the Greenes with no real answers.

The family was left to face the reality that their two sons had very uncertain futures. Either researchers would discover a cure, or doctors would fight the disease for years through medication and surgery until the boys’ bodies became unresponsive to treatment. On that dark path, the tumors might spread to other parts of their bodies or continue to grow.

“My whole world ended for a while after Zach was diagnosed,” says Brock. “The two people I loved most in the world, my kids, who were just at the point where they are getting ready to fly, were robbed. It took three or four months for me to process this but, eventually, I realized that we just had to change the future.

“I don’t feel very fortunate that I have this health situation with my kids, but I do feel very fortunate that I have skills useful in getting research started,” he says.

At the time, the largest brain tumor nonprofit, the National Brain Tumor Society (NBTS), was raising $8 million annually. The Susan G. Komen breast cancer nonprofit, by comparison, raises $420 million every year. Aside from their astronomical difference, the figures were shocking to the Greenes because the number of people diagnosed with breast cancer every year is little more than 1 percent larger than those diagnosed with primary and secondary brain tumors.

“The Susan G. Komen foundation has done an incredible job of fundraising. They’re a success story. You would just expect by looking at those numbers that there would be a huge difference in diagnoses, and that’s not the case,” says Spencer, who has known three fellow students fighting brain tumors during his time at Denison, one of whom was Liz Minter ’13, who died from the disease in May 2012.

Given the disparity, the Greenes knew they would need to raise awareness as well as dollars. So in 2011, Brock sent out a letter and a packet of information to college friends, neighbors, business associates—anyone he could think of. The message brought donations in with more speed and generosity than the Greenes ever expected. Friends, family, coaches from rival soccer teams, waiters at benefit dinners—everyone who heard of their situation seemed eager to help, to throw charity golf tournaments, to fundraise through walks and runs. “We wish this hadn’t happened to our kids, but a lot of beautiful things have come from this,” says Pam. Brock adds, “We have learned through this experience just how great people can be. I had no idea before.”

With the success of their campaign and the generosity of their friends, the Greenes began to think of ways to expand their sphere of influence. They decided in 2013 to create their own nonprofit, Oligo Nation, as a community for oligo families. Their hope was to empower others to learn how to fundraise for a change, just like they did.

“I realized that if I do everything right, we could raise $200,000 a year. And that’s never going to cut it. We need to get more of the 10,000 families in America who are living with this disease involved in fundraising if this thing is going to work,” says Brock, who connects with most oligo families through social media.

Since the founding of Oligo Nation, the Greene family, 300-plus registered Oligo Nation donors, and NBTS have raised over $1.5 million. With that funding, three major medical grants have been made to researchers at Harvard/Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of California-San Francisco, and the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

They also have built a community of support. Pam, who works for Levi’s, can list numerous examples of people they’ve been able to help by sharing doctor and treatment plan information and simply by being a family that understands what others are going through. “Our community has been amazing, whether someone is reaching out with meals or through emails, a donation, or a kind word,” says Pam. “Helping other people is a way for us to give back. And none of this would be possible without Brock.”

“It’s incredible what my dad gets done,” says Spencer. “Our days are 24 hours; his must be 48. Not only is he starting his own nonprofit, not only is he the owner of his own business, but he also has the time to look into every single thing that’s in the news. Every type of medical treatment that I have done, he’s found.”

It was Brock, for example, who found the experimental proton radiation therapy at MD Anderson in Houston, Texas, when his younger son’s tumor came back aggressively the summer before his senior year at Denison. Spencer, who took a break during the following fall semester to receive treatments, decided after his time in Houston to follow more closely in his father’s footsteps.

“It really hit me when I was in Houston that I needed to take this situation by the reins. I came back to campus with a whole new resolve as to how to deal with this. I needed to prove to myself that I could make a change, that I could be independent,” says Spencer, who was the philanthropy chair of Sigma Chi fraternity during his senior year.

And so he did. In addition to raising his GPA, Spencer fundraised well over $10,000 through multiple efforts: the Knobel 5K, which honors individuals and organizations that benefit Denison’s campus and community; a fundraising night at a Denison women’s lacrosse game; donations from friends; selling personalized “get your head in the game” silicone gel bracelets; and other events through his fraternity.

“It wasn’t like I was doing things I’ve never done before. It was that I was passionate in a way that I have never been before. And I think that that was the most fundamentally different thing about the approach to spring semester than previous ones,” says Spencer.

While his optimism and enthusiasm can’t be matched, they should never be mistaken for his natural disposition. For Spencer, these attitudes are calculated choices, and ones that come with sacrifice. “I choose to be positive. Should I worry about making it to age 40 or someday losing my mind? Should I worry about my mom losing a child? Where would that get me?” says Spencer.

Even so, life with oligo can be lonely.

“There are times when I wish that people would really understand,” says Spencer. “I have people who care about me, and I have people who would love to hear what’s going on in my life. I just don’t like worrying people. And I know if I start telling someone that I’m scared or that I’m lonely or that I’m worried about my future, I will feel like I am burdening them. I don’t like putting people in that situation because I know how it feels.”

After watching his only brother fight through multiple grand mal seizures, surgery, radiation, and many bouts of chemotherapy, Spencer is in a unique position. Not only does he know what it is like to have cancer, but he also knows what it means to be on the other side: to be powerless to help the ones you love.

“Seeing my brother sick was way worse than my own diagnosis. When you’re on the outside, you have zero input. That’s the hardest part. At least there are some things in my life involving my health that I can control,” he says. That means eating organically and working out every day, even if “every step I take feels like it could be the last one.”

“He is an amazing role model, even if he doesn’t necessarily want to be one,” says David Przybyla, Spencer’s psychology professor and director of organizational studies. Spencer consistently encourages those around him not to take their healthy bodies for granted. “One of the things I love about him is his elevator tirade. Every time people use an elevator to get from the first floor to the second floor, he says, ‘Hey, look, walk up these stairs.’ It’s kind of funny; he does it all the time.”

“Oligo has been my tool to inspire people,” says Spencer, “and I’m not directly fighting it anymore. My optimism will still be there. But I think the reason my optimism was so special was because my situation was so dire.” And for Spencer that optimism is a necessity. “I look at things that other people don’t because, to me, every little detail matters.”

In a similar manner, the now-23-year-old tends to his mind. Both he and his brother are avid crossword puzzlers and dedicated users of Lumosity, an online brain-training resource from a neuroscience research company based in San Francisco. After fighting a disease of the brain, cognitive function takes on a whole new level of importance. Though oligos can affect learning, the tumors didn’t stop either of the Greene boys from finishing college. Spencer graduated in December. Zach earned his degree from UCLA in 2011 and is now working toward his Ph.D. in physics at Columbia University.

When it comes to matters of the spirit, Spencer places faith in himself and the power of positive thinking. But even that doesn’t always help a new graduate face the future head-on, especially as he comes to terms with the fact that he has a future at all.

Spencer, who has no active tumor for the first time in years, will have an MRI once every three months to monitor his health. So he has begun his new chapter of life away from constant drugs and surgeries. And he is figuring it out as he goes, refusing to fear the cancer coming back.

For instance, Spencer flew down to San José, Costa Rica, in February for a three-month stay with the Workaway program, which connects applicants with international hosts and employers. After that, who knows?

“I’ve always planned for internships and this and that, but I’ve never really thought long term. I guess I wasn’t worried because I figured at some point I would have lost,” says Spencer. “Now I’m looking at the bigger picture, and I feel almost overwhelmed because all the things that I never thought would come to pass are here and happening.”

---Rose Schrott ’14 is an associate editor of Denison Magazine. To learn more about Oligo Nation or to contact Spencer or the Greenes, visit oligonation.org.