The life of an award-winning journalist isn’t all rainbows and butterflies. Sometimes, it’s a ripped stuffed bunny.

The seam of Bunny, Connie Schultz’s grandson’s favorite stuffed animal, ripped the night before she came to campus.

She made room in her suitcase for a sewing kit and Bunny with the promise of a healed animal upon her return. Despite a week of meetings with students and two public appearances, Schultz found time for the procedure halfway through the trip, sitting on the hotel porch on a sunny Ohio morning. People-watching as she closed up the patient, a mother-daughter pair walked by. Not even attempting to stay out of earshot, the daughter gestured to Schultz, saying, “See mom, that’s why I don’t want to do nothing with my life. I want a career.”

“Years ago, something like that would’ve really bothered me,” Schultz says. “Now, it’s just hilarious.”

Schultz is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist, and this year’s Nan Nowik Writer-in-Residence, a program established through the generosity of Denison Alumni Council Trustee Kathryn Correia ‘79 and Stephen Correia, as well as the Andrew W. Mellon Storyteller-in-Residence, funded through a combination of a grant from the Mellon Foundation and a gift from Denison alumna Sue Douthit O’Donnell ‘67.

She’s spent her fruitful career providing a voice for the underdog and advocating for social justice through her writing. She now serves as both a USA Today columnist and a Professional-in-Residence at her alma mater, Kent State University, in the School of Media and Journalism, teaching ethics, journalism, and feature-writing.

With a healed bunny safely stowed in her hotel room, Schultz headed to campus to help kick off Denison’s new journalism major as part of The New Storytellers speaker series, taught master classes, worked with students, and discussed the promising future of the discipline.

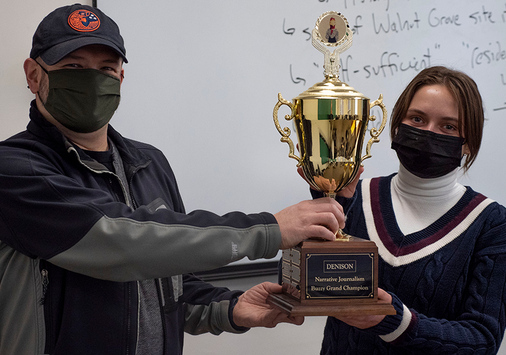

As the Narrative Journalism concentration at Denison gained momentum over the last few years, the need for an expanded Journalism program led to the launch of the new major and minor. This year, then, has been a time of expansion, evolution, and celebration within the program and with visiting journalists throughout the semester.

Schultz’s journey into the discipline is surely a success story, but it means little without what’s below the tip of the iceberg. She was a working-class, single-income kid; her father’s mechanic job sustained the family of six for over a decade. It wasn’t until just before she became the first in the family to go to college that her mother picked up a job as a nurse’s aide.

“I am a born outsider,” Schultz says, “and it’s one of my advantages. I am not uncomfortable talking to anybody.”

This is why she does what she does. Schultz wants to tell the stories of the people who change the towel dispensers in an office building or who make the heat puff up from city grates.

“Every issue is a woman’s issue,” Schultz says,“If I can get into something, it’s my issue.”

A Changing Profession

She believes there’s a disconnect in today’s journalism. Being brazen and rude as a reporter doesn’t work for the work that needs to be done. Instead, it’s about trust. It’s about body language, eye contact, and most of all, it’s about making sure human beings feel like they’re talking to another human being. Often, to break through the habits of today’s media, it’s about being blunt and asking hard questions.

“You have to tell a mother, for example, that there will be objective stories about how her son was shot and killed. You then ask her, in the midst of that, what does she want people to know about him?” says Schultz.

“It’s hard, but that’s the reason it’s equally as rewarding.”

Journalism has arguably been important for decades, and even centuries. So, why is it even more important today?

Connie Shultz thinks it’s because we’re in an unprecedented age of exposition – of truth and representation.

Among her many journalistic interests, Shultz is drawn to political coverage in particular. In her freelancing days, there was a mayor she covered who had a very young second wife. Her minimal presence in the media explained that she loved to knit.

“A couple of minutes into our conversation I learned that she didn’t even know how to knit. What she did have were strong views on what marriage meant in the realm of politics and patriarchy, ” says Schultz.

The mayoral campaign had simply handed favorable sentences out to reporters, and they ran with it.

Now, Shultz believes the work is dismantling this structure of journalism, and it’s happening.

“I’m most encouraged by young journalists. I know we’re asking you to fix what the last generation made, but you’re doing it with the open minds much of my generation never had,” says Schultz.

She asserts that the journalism of the future can only grow from the journalism of the past, and this generation of writers is the conduit of that change.

“We teach journalism because we are often the last stop to expose the corruption of those in power. We teach it to connect and to close the distance with readers, to show them our common humanity. We teach being incredibly close to a life-changing event yet still having the courage to write about it,” says Schultz.

The Meaning of Journalism

Schultz began the pandemic with five plants, and, according to her most recent count last week, came out of it with 64. She’s only a morning person because of her dogs, but she prefers to write at night. In her years as a single mom, she only had time to write in the middle of the night. It became a habit.

Journalism runs through Schultz’s blood. It’s what she’s meant to do. Her high school guidance counselor first brought the field up to her, and after a few years at law school killed her writing, she finally found that niche again and ran with it. She says she ran through quicksand and beds of nails and rejection letters and rejections straight to her face, but she got to where she needed to be.

“It’s so hard to have a universal idea of advice to give to young journalists because you all have your own strong interests and your own unique journeys. That is the advice in some ways, though. What you care about most is what you should be writing about,” says Schultz.

In the end, journalism helps us dig into our place in humanity and come face to face with what it means to be human. It bares the ugliest parts of people and the most beautiful moments we have and appreciates them all.

Journalism at Denison events are funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and a gift by Sue Douthit O’Donnell ‘67.