Journalist Sarah Schweitzer spent the better part of five months immersing herself into the daily life of a six-year-old boy and his family in order to tell his story. Some mornings, she’d wait outside their trailer at a campground before they had woken up and, some days, she’d join the boy, Strider, at school.

During a recent virtual conversation, Schweitzer discussed the reporting process behind the resulting story, “The Life and Times of Strider Wolf,” which Professor Jack Shuler teaches in his Literary Nonfiction class. The story exhibits the kind of empathetic reporting that the journalism program aims to foster.

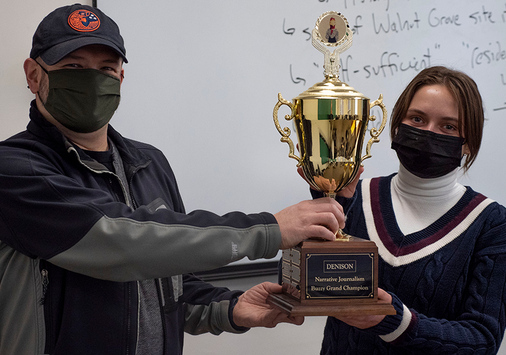

The online event was part of a Happy Hour series that connects journalism students with acclaimed writers and reporters. While Denison’s campus is closed amid the Covid-19 pandemic, students log into an online portal for a live video conversation with the guest of the week.

Sarah Schweitzer spent almost two decades honing her narrative instincts at The Boston Globe and the St. Petersburg Times. In April 2015, she was acknowledged by the Pulitzer Prize committee, which named her story “Chasing Bayla” a finalist in feature writing, calling it “a masterful narrative of one scientist’s mission to save a rare whale.” The next year, “The Life and Times of Strider Wolf,” was named a Finalist for the ONA 2016 Feature Award. Schweitzer is currently a freelance narrative nonfiction writer and working on a novel in New Hampshire.

“The Life and Times of Strider Wolf” chronicles Strider, who is poverty-stricken while living with his grandparents in rural Maine and, having faced an abusive past, embarks on quests for love, security, and hope.

Strider’s story is another in Schweitzer’s string of reported stories about children who seem to shine in some aspects of their lives while also dealing with adverse circumstances, including homelessness and living in the foster care system.

She said she’s often drawn to writing about, “This idea of a bright light in the middle of a mess.”

Like any journalist, Schweitzer knows that publicizing children’s lives raises ethical conflicts, but Schweitzer takes great care to tell the stories of children in a thoughtful, humanistic way.

“I think it’s often important to have a small child’s voice, as difficult and as potentially ethically challenging that could be,” she said. She pointed to the lack of immediate news coverage about children in detention centers, of which the disturbing circumstances are sometimes not exposed until after the fact.

Instead of finding a story that fits the narrative for a perceived fact or demographic within a population, Schweitzer explained that journalists should not go into a story with an agenda. She said, “Ask yourself, where can I meet this person in the middle? What’s going to work for them?”

Schweitzer and the photographer who joined her reporting trips were able to build trust by listening to the family’s troubles, openly witnessing their lives.

“This family was going through so much upset … I think it meant a lot for them to have reliable people there listening, because they couldn’t get anyone in the state government or their social workers to listen to them, to do what they wanted, but we would. We would show up,” she said.

Schweitzer addressed authorial power and the precarious nature of shaping a story about people’s lives — you decide the time frame and which elements stay in or fall out.

“After every reporting trip, look at your notebook and ask what’s a scene … Choose the scenes based on what’s most powerful, what’s most revealing,” she said.

Schweitzer reminded students that, while the work behind journalism is hard, the results are meaningful. “Stories will always matter … Looking at how to tell stories is invaluable,” she said.

The Happy Hour series for journalism students at Denison is funded in part by the Andrew W. Mellon “Writing in Place” initiative and a gift by alumna Sue O’Donnell.