Physics Professor Dan Homan conducts research on distant, active galaxies by recording and analyzing radio and magnetic waves.

Popular lore has it that nothing can escape a black hole. Dan Homan knows better — at least for material very near the black hole. He studies the high-energy particles and radio waves that emanate from these cosmic gravity wells to gain a deeper understanding of them and their role in the universe.

Homan conducts research on distant, active galaxies by recording and analyzing radio and magnetic waves. The galaxies are billions of light-years away — and they are huge. “Our galaxy is considered large,” said Homan. “But next to these, ours would seem tiny. These can be 10 to 100 times as big.”

Only a very small percentage of galaxies are considered extremely “bright.” They emit high levels of energy that Homan can observe by tapping into a global network of radio telescopes. By linking the collected information, astronomers have essentially built a telescope the size of the Earth. “We can look into the very heart of distant galaxies and really see what’s going on,” he said.

Homan and fellow scientists believe supermassive black holes are generating strong magnetic fields at the centers of these extremely bright galaxies.

These fields are created when objects “fall” into the black hole. “As things fall into the center, they have to give up some of their energy,” Homan said. “Every time something falls in, something else has to carry away some of that energy.”

That explains the phenomenon scientists call “jets,” powerful streams of plasma, with high-energy particles oscillating in magnetic fields spurting away from black holes. By tracking a jet’s bright center over time, Homan and his team can measure rates of flow. And what they see sometimes defies the laws of physics.

Jets can appear to be flowing at a rate 30 or more times faster than the speed of light. Yet a fundamental principle of Einstein’s theory of special relativity states that nothing travels faster than the speed of light.

What’s happening?

Homan said what we are seeing is a cosmic version of the Doppler effect. Similar to how we experience the loud noise of a train barreling towards us, only to fade as it moves away, a jet’s speed can appear to be faster or slower depending on our point of view in relation to the direction of the jet.

It’s really a matter of geometry, Homan said. Like the roar of an incoming train, “we’re receiving the signals faster than they were emitted, because we’re staring down the ‘throat’ of the jet.”

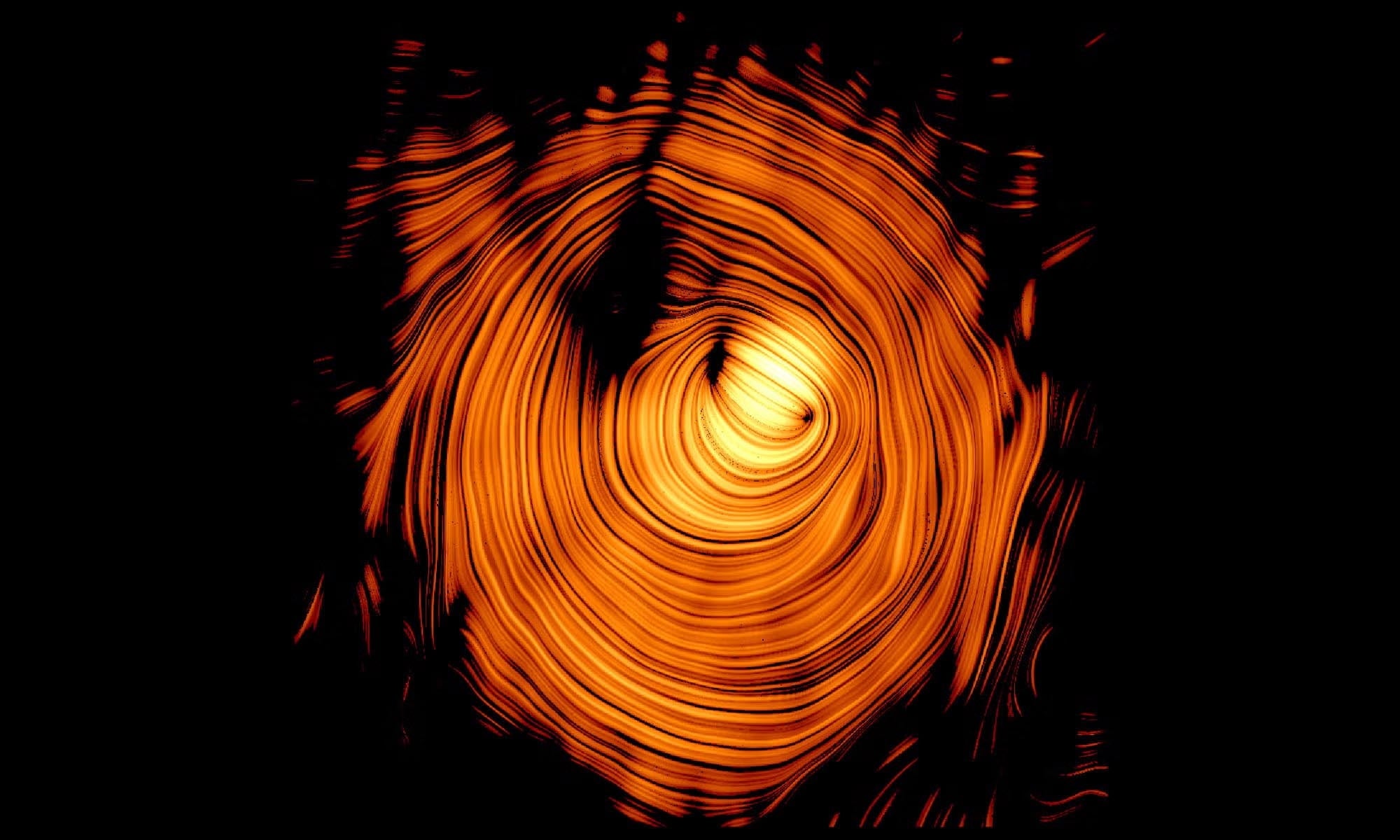

Mapping the "Eye of Sauron"

Homan and his team track a jet’s movement by stacking maps of the data. The resulting image of one particular jet, Blazar PKS 1424+240, is stunning.

“I was blown away by it,” said Homan. “My colleague calls it the ‘Eye of Sauron.’”

The journey to Sauron wasn’t easy in The Lord of the Rings. That’s also true in astrophysics. Jet maps are generated by using data assembled over decades. Stitched together from multiple telescopes, the data is rife with small errors. Before it can be used, the data has to be cleaned by running it through an algorithm.

That algorithm was developed at Denison, with the help of physics major Jaelyn Roth ’23, who worked on the project over two summers as a research scholar. Today, Roth is a doctoral student studying astrophysics at Vanderbilt University.

Contributing to current research is one of the benefits of Denison’s small faculty-to-student ratio and robust research opportunities.

“Denison students are still working on this, answering new questions,” said Homan.

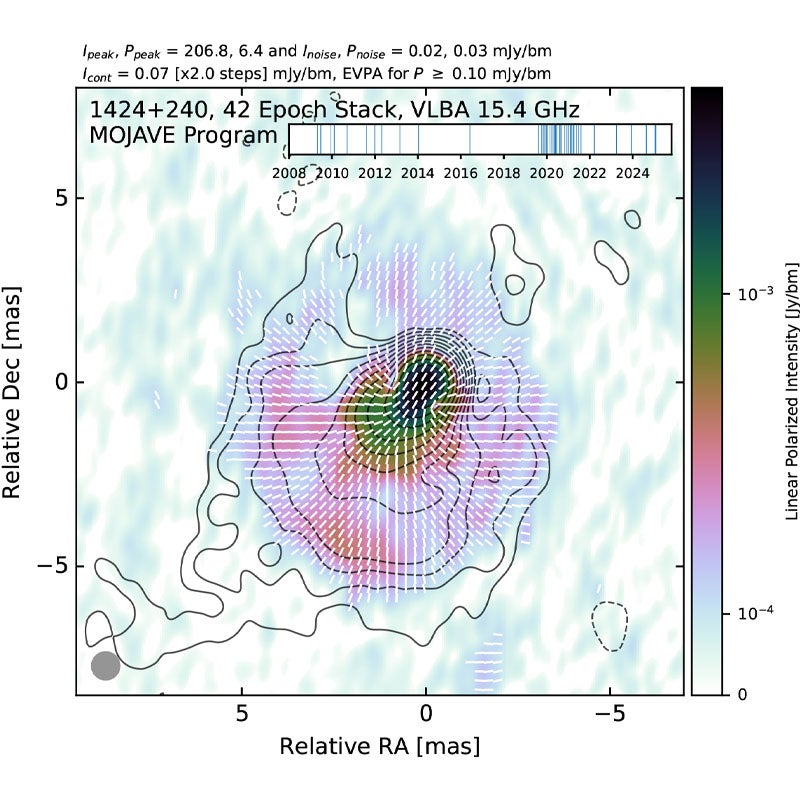

Roth is listed as a co-author on a paper with Homan that shares the new technique with the community. Homan and his team have recently used the technique to help reveal hidden details in PKS 1424+240

Homan and fellow scientists studied a time series of jet maps to develop their theory.

From black holes to neutrinos

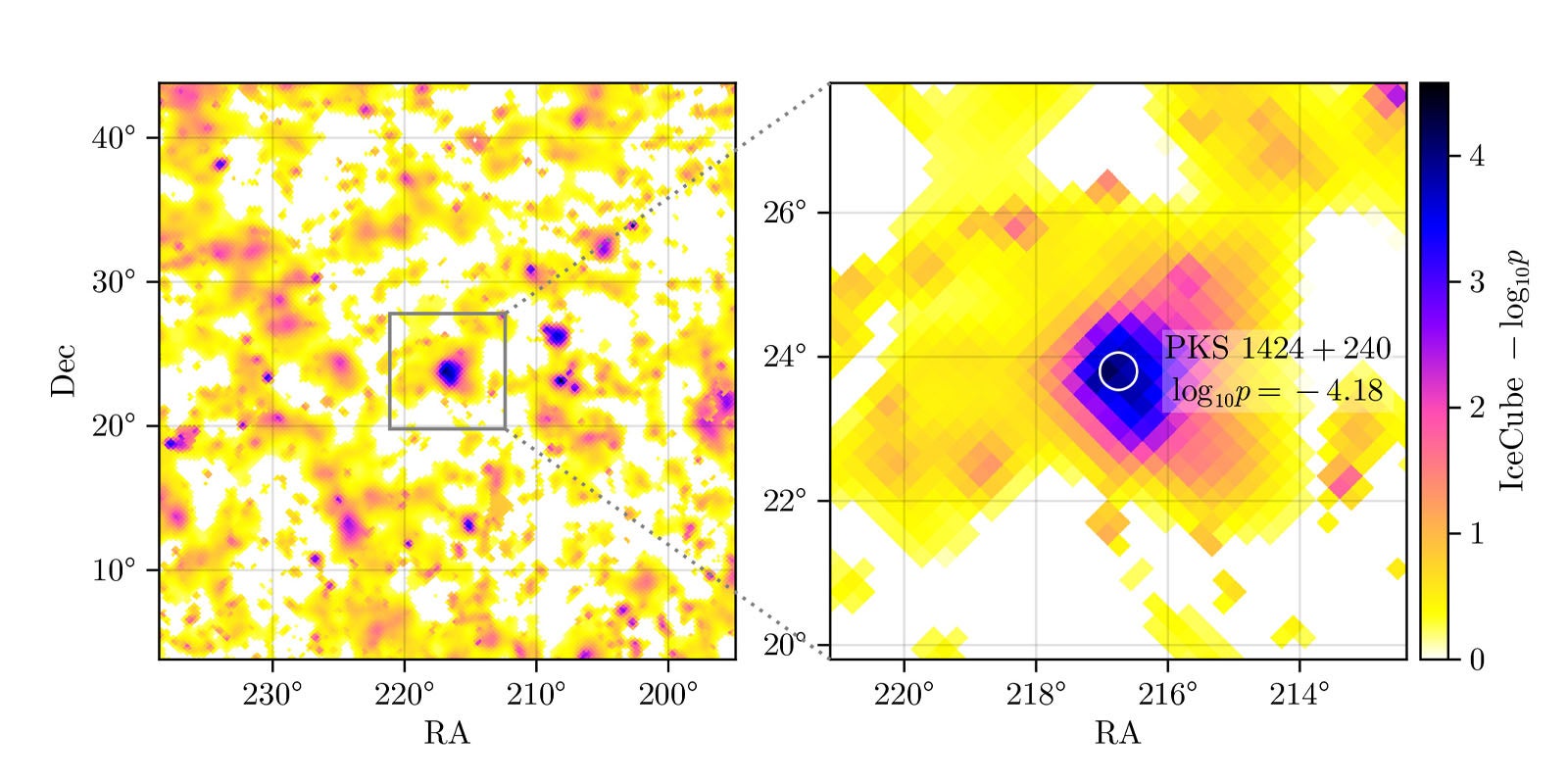

Homan’s latest published research applies these theories to observations of neutrinos.

Neutrinos are abundant fundamental particles, but they are hard to find. With no electric charge and little mass, they are difficult to observe and measure.

As neutrinos pass through Earth, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in the Antarctic can map them. Their paths seem to point straight back to massive black holes. This could be a verification of their source. However, nothing is quite that simple in astrophysics.

Observations of PKS 1424+240, a jet that produces high rates of neutrinos and creates gamma rays, suggest it is relatively slow.

“However, the opposite should be true,” said Homan. “Much higher speeds should be needed to generate these particles and waves.”

This effect is called the Doppler Factor Crisis. Homan’s research shows that, once again, geometry holds the answer.

This time, we’re seeing the train traveling straight toward us — we’re not seeing much movement, but the decibels are screechingly high.

The stacked image of the jet expands like a cone over time, and we’re looking right down into its center as it moves toward us. “We know this because we can now see magnetic field lines in almost perfect circles,” Homan said.

He says this near-perfect coincidence explains why scientists previously estimated speeds for this jet that were too slow to produce high-energy particles: hence the Doppler Factor Crisis. Because Homan and his collaborators can now stack these images over time, our view today tells a new story.

“We now estimate its Doppler factor to be a whopping 30,” said Homan. “That would make PKS 1424+240 one of the most powerful galaxies in the sky — easily capable of producing the high-energy gamma-rays and neutrinos.“

Science is a long game

Homan is one of the founders and leaders of the MOJAVE project, a multi-decade program that has been monitoring the polarization and total intensity of jets generated by supermassive black holes since 2002.

MOJAVE is run by an international team that has produced dozens of papers now highly cited in the scientific community.

“A long-term project gives you benefits you don’t get in a single experiment,” Homan said. “As we went on, every-thing we found raised a new question.”

Over the years, many of Homan’s students have gained valuable experience by collaborating on the project.

“It’s so good for students to be involved in cutting-edge research,” said Homan.

True to form, this most recent paper has been published, and the work on MOJAVE continues. “Right now we’re looking at a way to measure the speed of jets over time by using more advanced data analytics techniques,” said Homan, who directs Denison’s data analytics program in addition to teaching physics.

MOJAVE’s previous research was based on people looking at and interpreting maps, which is labor-intensive and subject to human bias.

Homan’s new data analytics approach requires minimal human intervention. He’s excited by the results thus far.

“The algorithm seems to be working and may already be detecting new information,” he said.