In the summer of 1937, when I was 12, Grandpa became ill. We never knew it because we were sent away to the Spalding farm in South Woodstock, Connecticut. Dr. Spalding was Grandpa’s physician in South Weymouth and the Woodstock Spaldings were his cousins, and it was closer to home than the camp we’d been going to in Maine. We suspected nothing.

I loved the farm. Bare feet and bib overalls, cows to milk, cornfields, and a swimming hole. The farmhouse was already two hundred years old when we got there and had only two electric lights, a pump for water in the kitchen sink, and a big iron woodstove. There was a cold room, where sides of meat and bacon hung, and a crock to store the doughnuts Aunt Ruby served up out of a cast-iron cauldron of boiling oil on the stove. She’d pluck the glistening doughnuts out with a long, charred stick and drop them into our outstretched hands, and we’d bounce this scalding, greasy delight around until it wouldn’t burn our mouths, and then we ate it. There is nothing in this world I have ever tasted in the finest restaurants around the globe that could match the heavenly taste of those doughnuts.

That summer on the Spalding farm came to an alarming end when we arrived home and found the door to Grandpa’s room closed to mute the sounds of his agony. The doctor and nurses would open his door, and for one frightening moment we would hear the full-out cries of our great soldier in the grip of battle with death, and then the door closed again. He faced that dark angel with curses and disbelief. His bedroom had twin beds, and he was moved from one bed to the other all day and night as he drenched the sheets with the sweat of his relentless torture. Sometimes he slept. Or the pain receded for a brief term. We lingered outside the door, sick with fright, listening for the sounds of our champion.

My sister June and I were sent away before Grandpa died. Only Alberta, our other sister, stayed with our housekeeper, Nettie Wigton. June and I were to go to Cleveland and stay with strangers.

Before we left, I was brought in to say goodbye. It was not put to me like that, but when I stood outside the door of Grandfather’s room and waited, I knew what this moment would mean to me for the rest of my life. Goodbye, Grandpa. Goodbye, my captain.

In Cleveland, June and I were enrolled for the year at St. Augustine Academy. And while Grandma remained in South Weymouth for Grandfather’s last days, we were sent to live with some people who were friends of Grandma’s housekeeper, Francis. They lived in a substantial but much more modest home than Grandma’s twenty-room mansion, not in a fancy part of town, and perhaps this was the source of the sourness with which the man of the house received us. He made it clear we were unwelcome. His wife was kind enough, considering the burden our coming had laid upon her home, and their young son was a decent boy. But the man was a bear trap ready to spring, so we crept around him.

The new school was a major diversion, and since we were not Catholics, I noticed a lot of strange things about St. Augustine. The grounds were very nice, and there were buildings that looked like castles, but I kept seeing so many statues of a woman with her head tilted down, sometimes looking at a baby, that it gave the whole place a feeling of sadness. She seemed to be slightly unhappy, this woman, although if you got close enough, there might be a tiny, sweet smile lurking under the stone cloth that hung over her head. I was 12, and I remember thinking, Could this be my mother?

There were real people called nuns all over the place, with real cloths over their heads, black cloths that hung over stiff white picture frames resembling starched collars that covered everything except their foreheads, eyes, noses, mouths, and chins. Some of these women appeared to be pretty ferocious. Since all that showed was their faces, I learned to read their disposition from their eyes and mouths.

There was a young one named Sister Ernestine. I wished she really was my sister, or maybe my mother, because I could see in her face that she was a very nice, kind, soft person. I found out that Sisters couldn’t be mothers, but I’ll bet she could have been a nice one.

One evening at the house where we lived with the strangers, we were having dinner and the man of the house was angry at June. An empty jar of chocolate sauce had been found under her bed, and the man was accusing June with very near to white fury in his voice. “You will be punished. This is stealing! You will stay in your room for a week on bread and water.”

A silence followed. June’s head was unbowed. She did not apologize. The man picked up his evening newspaper and said, “Oh, by the way. You’ll probably be interested in this. ‘Stetson Shoe Dealer Dies.’” Then he read Grandpa’s obituary to us.

June began to scream. She broke from the table and ran into the night, disregarding the man’s furious orders to “Get back in here!” I ran past him and called for her to wait for me, but she was lost in the neighborhood shadows. The man ordered me inside. I turned on him with an authority I didn’t know I had: “I’m going to find my sister!” I sounded like Grandfather. I would have killed the man where he stood. He saw it and retired. I looked for June in the maze of neighborhood streets, under a cold moon, and I finally found her. She would not stop sobbing. We wandered together until the terrible shock began to go away, and silence took over. “Look at the stars, Harold,” she said. “You see how bright they are? Grandpa is up there, and he sees us.” That is how we found out Grandpa died. The next morning my first class at St. Augustine was with Sister Ernestine. She always started it off with a prayer. When the class was assembled, she waited until it was quiet. Then she said, “This morning we are going to say a prayer for Harold’s grandfather, who has gone to heaven.” It was an act of kindness I would always remember.

I never got a chance to grieve over Grandfather’s death. The cold hearth ruled over by the man did not allow for it. This haunting grief stayed inside me.

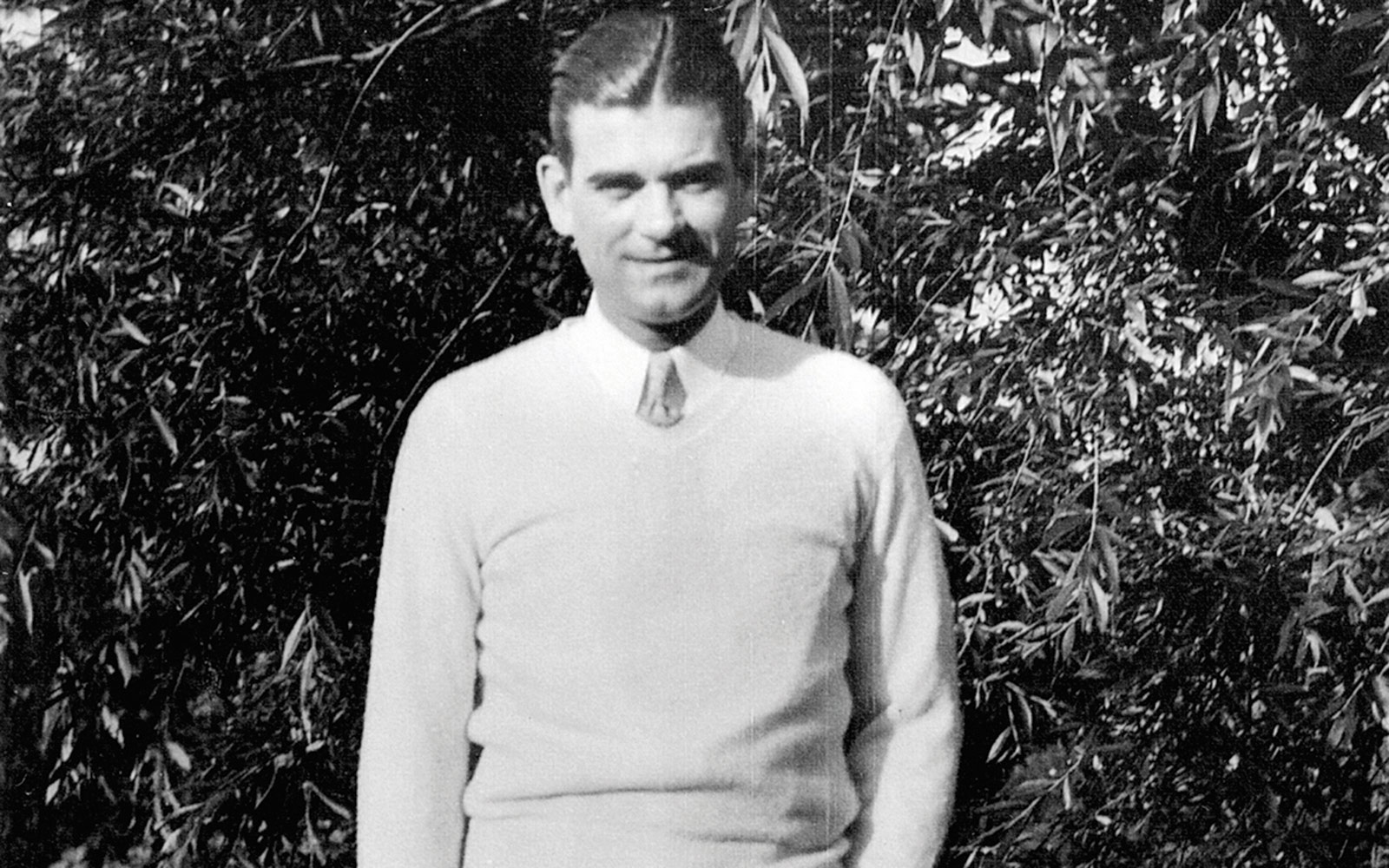

Our father never showed up at the deathbed, of course, having been put away in the insane asylum. Our mother didn’t seem to exist at all. She had tap-danced her way into infinity. Or Hollywood, which is where she was last sighted. Our father eventually got out of the asylum, since he’d never been pathologically insane in the first place, whereupon he took to the road, riding the rails to California in search of my mother. He nearly froze to death under a boxcar going over the Rockies. From time to time he sent a message by Western Union. It usually read: “Am broke. Send $50 General Delivery Phoenix. Harold.” We had the same name: Harold Rowe Holbrook. I’m Junior. I hoped that was as far as I would follow in his footsteps. The telegram came to Grandma, who always sent him the $50. There was a picture of him in her room. He was tall and thin and handsome, with dark eyebrows like Henry Fonda’s, and he was wearing white flannels and a white sweater and his dark hair was slicked down. I didn’t know what to make of this movie star father who looked like Henry Fonda and was dressed in white.

Where was he? Did I look like him? Did I want to see him? Every time a telegram came from Phoenix, Fairbanks, or Juarez, I told myself, “Don’t go crazy or you’ll end up like him.” Once, I remember seeing him outside the house in Cleveland fighting with my uncle Al. I peered out the window and there was my father throwing punches at Uncle Al and cursing him. My father was winning because he was wildly aggressive, like a crazy person, his arms swinging like windmills, and Uncle Al couldn’t get out of the way. Then the police came and took my father away. Back to the asylum? All I knew was that he was gone.

Now Grandpa was gone, too, and we were back in Cleveland. The house was big and empty and there was no more grief in it for Grandpa than there had been at the man’s house. All I could do was go upstairs to Grandpa’s big bedroom and bath and the friendly den that still smelled of his cigar smoke and remember him. In the middle of the house, opposite Grandma’s room and facing Lake Erie, was a large room with a heavy four-poster bed. This was June and Alberta’s room. It was here that Grandma assembled us when she returned with Alberta from the funeral in South Weymouth. An air of suspense tainted the room.

“I want to tell you children something. I do not like girls. I have loved this little boy ever since I saw him in the hospital, my blue-eyed baby boy. I will do the best I can for you, but I do not like girls.” I remember the shame and disgrace I felt for all of us. I suppose she was trying to be honest, and she must have felt frightened and overwhelmed, but it was the worst thing she could have said. A sense of survival set in from that moment on. It was a furtive thing, a layer of desperation underneath our daily existence, like quicksand. We were bound together in the name of brother and sisters and the knowledge we had of one another’s fears and sorrows, but on that day we were sent forth upon our private journeys, looking for safety and looking for love.

June and Alberta were also at St. Augustine that year, but I don’t remember spending much time with them. They were girls, and when they were with other girls they became different people. Girls laughed too much and looked as if they had secrets against boys and that made boys nervous, so for my sisters and me it was almost like going to different schools. But there was one girl who was different. She was quiet. She had dark, interested eyes and dark hair and her face was in repose most of the time. She had small curves on her body, and I found it hard not to look at her a lot. Sometimes I saw she was looking at me. One time she smiled. I noticed she walked home in the same direction as I did and one day we happened to leave at the same time, so we walked together. I had begun to consider the idea of asking her to go to the movies. I’d never had a date with a girl, and I had just turned 13 years old. It was time. Now or never.

“Uh.”

She smiled at me. “Yes?”

“Do you like the movies?”

“Sometimes.”

“Would you go to a movie with me?”

“When?”

“Saturday.”

“I think so, but I have to ask my father.”

I hadn’t thought that far ahead. I had to ask Grandma, and that took a measure of courage, too. I was her blue-eyed baby boy and wise enough at 13 to know she did not expect competition. She was taking me out to Stouffer’s with her that night. The girls had misbehaved and were being punished by not being allowed to go, which was no punishment at all to June and Alberta. They made their own fun. So I sat in a chair in Grandma’s room while she preened in front of the mirror, dressed in a flimsy kimono, and curled her hair with the hot iron, spitting on her fingers to test its heat.

“Grandma, I want to go to the movies this Saturday.”

“Which movie do you want to see?”

“I mean with a girl.”

“A girl? What girl?”

“A girl at school.”

“Who is she?”

“She’s a nice girl. She said she had to ask her father, so I’m asking you, too.”

“What’s her father’s name?”

“I think it’s Mr. Rodzinski.”

“That sounds Jewish. What does he do?”

“I think he’s a bandleader. He has a band.”

“You want to go to the movies with the daughter of a kike bandleader?”

“Yes, Grandma.”

“Well. We’ll see.”

It turned out that Mr. Artur Rodzinski was the conductor of the Cleveland Philharmonic Orchestra, a civic resource beyond the cultural summits of my family’s adventuring, but clearly on a higher social plane than Harry James, so I was allowed to go.

This brings me to the astounding realization that nobody ever read books in my family. If they did, books were never mentioned. Nor did they go to concerts or the theater and certainly not the ballet. They lived in a limbo world apart from such foolish fancies, and as I was to learn years later, so does much of America.

Our mother and father danced for us and must have gone to the theater and done all kinds of exciting things, but that was never talked about. They were strangers. Our mother was never mentioned. Was it because she was in show business? Because she danced? Because she was different and that was an embarrassment? And so was my father, because he did not want to go into the shoe business. Did they put him away because he was different?

The creative urge is an impish shadow that falls across a child’s path as if by accident, giving some credence to the notion that it is subversive. Thus it was that I began to dance like Fred Astaire. My performances were secret and took place in the basement in a recreation room with a shiny varnished floor thirty feet long and a windup Victrola sitting alone on the dance floor. And there was a spooky, impish bonus: an album of records belonging to my mother. The day I made this discovery, I plucked one out of its sleeve, put it on the turntable, and cranked up His Master’s Voice. The glorious sound of a man singing “My Blue Heaven” poured out of the horn-shaped speaker that spread like a crown above this magic box.

There was no one around. I started to move, spinning and pirouetting in wild arcs. As I gave myself up to the thrill of it, I performed feats of creative contortion that would have been impossible had anyone been watching.

Since the recreation room was at the far end of the enormous cellar running the length of the house, my clandestine recitals remained secret for some time. Then June caught me at it and started to riffle through our mother’s record collection in wonder and sober delight. When this secret trove was revealed to Alberta, they both spent hours listening to the collection, knowing that our mother’s hands had held these records and that she had danced to them.

The recreation room became a kind of hiding place for us, a place to dream things and pretend, where we spent time alone or with each other. Grandma never came down there, nor did Francis. There was a door in one wall. It was always locked, and we never gave it a thought. One day I found it open. So I went in, and when I snapped on the light, I saw that it was a trunk room and right in front of me was a wardrobe trunk standing open. It was upright, with clothes on one side hung on special little hangers, a woman’s clothes. On the right side were drawers, gray and quite deep. I stared at this strange sight for a while, wondering whose trunk it was and why it was open. Then I pulled out one of the drawers.

Baby shoes, baby clothes, little silver spoons and forks, two little silver cups. On one cup was engraved the word “Sunshine.” Could that be me? I opened another drawer and found some long, rolled-up pictures of pretty women in a chorus line onstage. They were bending over, holding their knees, and smiling. They didn’t have much on. Under one of the women was a little arrow.

The woman above the arrow was onstage with a man, and she was holding a guitar. The name Joe Penner was written in a margin and that had a familiar sound. One of the big pictures had a caption: “George White Scandals.” There were letters, a batch of them tied together with a blue ribbon. The reality of what I had discovered began to dawn on me. I slipped a letter out and read “Dear Aileen…” That was my mother! I looked for my father’s name at the bottom of the letter, and it wasn’t there. There was another man’s name. Russ.

These were my mother’s things. This was her trunk. She was on the stage. She was in a big show about “Scandals,” and I had never been told. She was in show business. She was on the stage! Our mother! Was our father on the stage, too? Who was the man who wrote these letters my mother kept with a blue ribbon around them? I started to read the one in my hand. It was very personal, about love, and I was embarrassed so I stopped. I felt like a thief stealing into my mother’s life. These people were strangers.