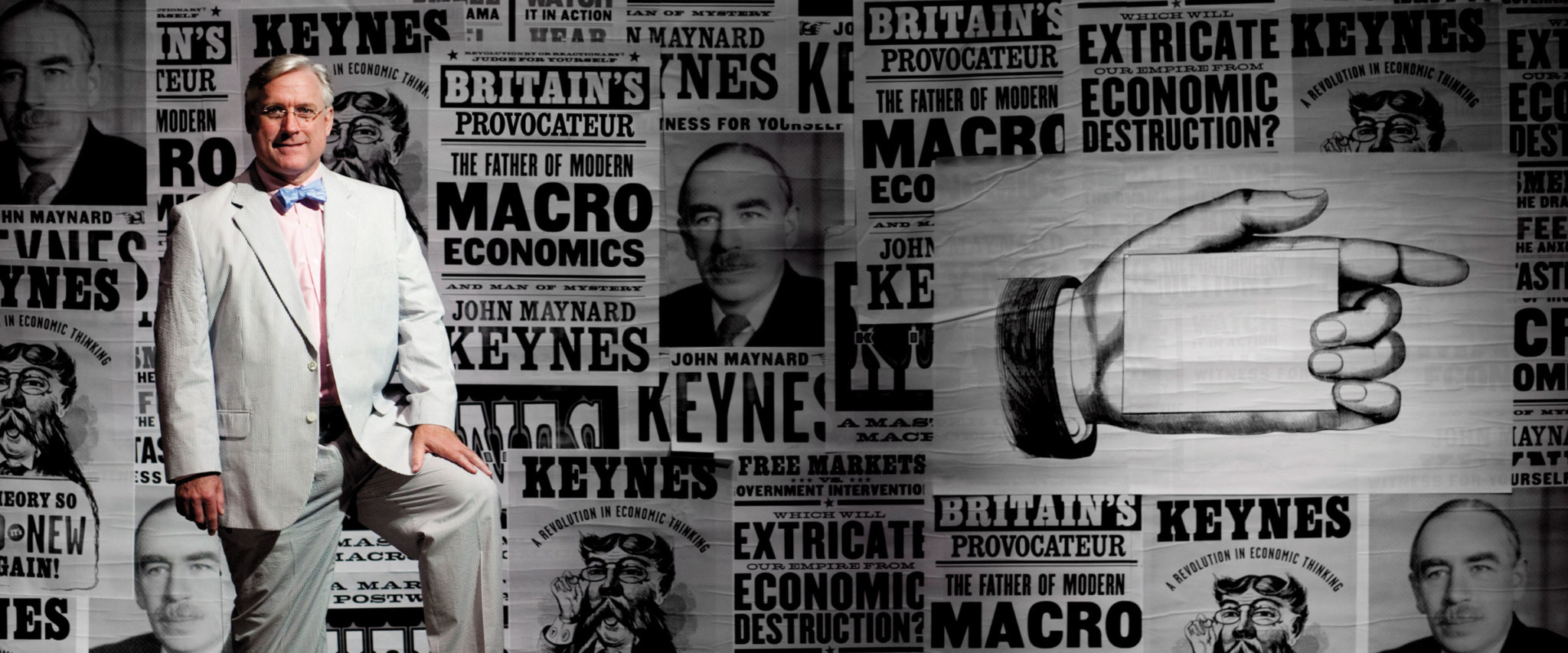

You’re teaching your first day of Econ 101. What do you say to introduce Keynes?

That’s a tough question because most people’s understanding of Keynes is as a caricature of the real man. The standard picture of Keynes–the caricature– is that he’s the man who wrote The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936, and that politicians then used his ideas to save capitalism from the effects of the Great Depression. Later, his name became synonymous with government intervention in the economy. But much of this story just isn’t true. Keynes did solve the analytical puzzle of explaining how mar- ket economies rise and fall. We didn’t have an analytical model to explain either booms or depressions before The General Theory. But his ideas were not used by governments in their responses to the Great Depression.

So if Keynes didn’t save capitalism, how did his name become synonymous with the idea of government spending to stimulate economies?

What really happened in the ’20s and ’30s was that the national governments in most of the industrialized democracies began to intervene for the first time to try to help their economies. Germany, France, the United States, Italy, Japan, Sweden, and Norway either cut taxes or increased spending to try to stimulate their economies during the Depression. But they all did it for different reasons, none of which had to do with John Maynard Keynes. In Sweden, for instance, two political groups who traditionally had battled each other– farmers and urban workers–realized that running deficits to stimulate the economy was something that they could agree on. In Japan, the military demanded re-armament and the only way they could do it was to borrow money and create a deficit.

In the end, World War II happened and everybody ran huge deficits. Our economy started to boom during the war because of war production. But people remembered that after the First World War, economies crashed everywhere when we stopped production and millions of people lost their jobs as a result. So during World War II, economists tried to think about ways of avoiding that scenario. What Keynes did was give economists everywhere–in Japan, France, Italy, Germany, England, and the United States–a common language for explaining why running deficits could stimulate their economies and for explaining the ways in which they could manage economies going forward by using fiscal and monetary policies. So the Keynesian model wasn’t really used widely until the 1940s. It simply became the label that stuck to a set of disparate experiments. So 1945 though 1975–what the French call “the 30 Glorious Years” and others just call the “postwar boom”–became linked with Keynes. Even President Nixon said in 1969: “We’re all Keynesians now.”

The late 1970s and ’80s saw Reagan and Thatcher usher in a new era of economics that was decidedly different from Keynes’ policies.

It really was. In the public mind, I think, Reagan and Thatcher represent the move away from Keynesianism. Keynesianism had been beaten up pretty badly in the 1970s because, for the first time since World War II, we simultaneously had high unemployment and high inflation. Two oil embargoes raised prices radically, causing lots of unemployment as companies started laying off workers in the face of falling demand. It was a mess. Keynesian tools didn’t offer an easy answer. There was also a concerted effort in the financial press and out of several right-wing think tanks to blame what was happening on Keynesian policies.

Milton Friedman was one of the first economists to rush in with an alternative to Keynesian policies. He had been making strong arguments against Keynes for years, but suddenly people began to listen to him. He said, in effect, “You just have to set the growth of the money supply at a steady level. Inflation will stop, and we’ll get good stable economic growth.” But in order to believe that this simple solution would work, we’d have to assume many things about the economy that turn out not to be true. Once the Federal Reserve adopted Friedman’s policies in 1979, they almost immediately had to abandon them. But the failure of Freidman’s policies did not lead to a return to Keynesian ideas in the 1980s. Instead, new, more analytically sophisticated theories were developed in an effort to show that markets work best when there is no government intervention.

To the misinformed public, it became a battle between the good guys and the bad guys. Keynes became the figure in favor of heavy state intervention, and so, the bad guy. The good guys were people who wanted the government to do nothing or very little and to let the market function unimpeded.

But as I said a minute ago, this is a caricature of Keynes’ ideas. In the first place, he did not believe that the government needed to “manage” the economy. He believed that when there was a depression or a collapse in the financial system, public works projects (what we would call infrastructure investment) could stabilize the economy and help to get growth started. But he did not believe that the government should be involved in running the economy or using fiscal policy to guide the economy when it is doing well.

In the second place, he did not believe in running deficits in the government budget. It’s tough to explain, but long before the Great Depression, Keynes had argued publicly for taking capital expenditures off of the regular government budget. He argued that the government should keep its books the same way that corporations do and use a separate capital budget. So he argued during the Second World War that it was not part of his plan to run government budget deficits. He believed in stimulus programs that paid for themselves; he advocated infrastructure projects that would generate the income necessary to pay off the loans used to finance them.

The movement between free-market proponents and Keynesians seems cyclical–sort of reactionary, like politics. Will we find that Keynes will only be in favor until the next inflation crisis?

Crises in capitalist economies have always been there and will keep coming back. When the economy is in crisis, we want one set of ideas about how to deal with that crisis, and when it’s functioning pretty well, we tend to put those theories away and get out the free-market ideas. Actually, this is not so far from what Keynes believed. There are also contemporary economists who see the need to occasionally intervene, such as when there is a crisis in financial markets.

Nouriel Roubini is a hot name in economics right now. He predicted what happened in 2008. He said we would have a mortgage finance crisis that would cause investment banks to go out of business, and the effect would ripple through the whole global economy causing massive recession. The line he’s selling now is that we need Keynesian-like ideas–government expenditure– during the times when a lot of financial speculation has caused the system to crash and resulted in widespread unemployment. But Roubini is also saying that when we emerge from the crisis, we should shift back and let markets do their work.

But, of course, there are people on both sides of the debate who think it has to be one thing or the other, all the time. Either the government always has to be involved in managing the economy, or that it should never be involved in stimulating the economy. What we seem to get is a cycle of public opinion in which we need constant government intervention, or nothing.

Who knows, maybe Keynes and Roubini are the wave of the future? Maybe we’re done with the simplistic ideas that it’s all or nothing, one way or the other.

What’s your take on that?

I think there’s a lot to like in the idea that markets often function well, but occasionally perform so badly that the government needs to act to right the ship. I’m not an anti-market person. I think allowing the market to fluctuate does a lot of good things for us. I do think financial markets have a tendency over time to slip into instability and crisis, and when that happens, a lot of people who have not played any part in causing the financial crisis get hurt. It’s not in the interest of society to make millions of people suffer unemployment while these periods of instability work through the system. We do have the tools to get the economy back on track and to keep people from suffering unnecessarily.

My own take is that we do not need that kind of active intervention in the economy during normal times.

The essays in the book you’ve co-edited, The Return to Keynes, argue that Keynesian theories have come back in vogue, although no one has really talked about that until now.

My point, and the point of the book, is to simply document that although leaders were espousing free- market ideas during the year preceding the financial crisis in 2008, they were actually using fiscal policy (taxes and expenditure) quite actively to try to better manage the economy. That is to say, the free-market ideas that had prevailed in the 1980s and 1990s that suggested there was never room for government intervention in the economy had quietly gone into retreat among politicians and policy makers. So, in this sense, Keynes had made a big comeback before 2008. Countries using the euro made a growth and stability pact in 1999, which meant that their deficits had to be limited to a certain size and that they could only be used for two or three years. Germany and France violated that pact immediately by creating larger deficits for longer periods of time in the early part of the last decade. And of course George W. Bush–very purposely and explicitly–ran huge deficits for eight years. He used a lot of supply-side rhetoric to rationalize what he was doing, but he also said that his deficits would stimulate the economy. And his means for stimulating the economy had little to do with traditional supply-side arguments for investment in new plants and equipment: One of his first acts in office was to send us each checks to our mailboxes and tell us we needed to use the money to go out and shop. That’s as Keynesian as it gets. Was that a good thing or a bad thing? That’s up for debate. But it was not supply-side economics.

What are critics saying about the rise of Keynes?

The financial crisis is now being followed by a fiscal (or budget) crisis. Most of the G20 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development now have what looks to be unsustainable growth in their deficits. I think people are looking back on what happened–the people who opposed the stimulus packages–and saying, "See what Keynesianism caused? Greece is going to go broke. Spain will go broke. Portugal and Ireland will go broke. And the United States could go broke too." But we're not going to go broke because of the stimulus. If we're in fiscal trouble in the United States, it's because of all the expenditure that took place before the stimulus package was passed in 2009 and the commitments–such as a new Medicare drug benefit and the two wars we are fighting–that were undertaken prior to 2009. The problem for all the countries that have fiscal problems is that they undertook emergency stimulus packages after accumulating years of deficits. It does look bad for some of them.

Your book seems to come at a rather fortuitous time. What signs did you see that compelled you to collect these essays even before the crisis arose in the fall of 2008?

The truth is that there was a real dollop of good luck. In 2006, my co-editors, Maria Marcuzzo and Toshiaki Hirai, asked me to help them pull together a series of essays for a book. I said: "I think that something has happened that isn't being talked about. I think we've moved back to using fiscal policy to try and guide the economy, whereas 10 years ago, cutting-edge economic theory suggested that we shouldn't be doing that even during financial scares like the dot-com bubble or when the economy was being jarred by the fears associated with September 11th. And maybe we should address that in our book." So we started in on the book, and then the bottom fell out of the economy. Suddenly there was a mortgage crisis. Bear Stearns failed. Lehman failed. And then there was an international financial crisis and everybody was wheeling out big expenditure packages to stimulate their economies. We thought, "Wow. This is like Keynes on steroids." We just happened to be in the right place at the right time.

There was a moment in October 2008, when former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan admitted before a congressional panel to seeing a flaw in his free-market beliefs, which he had held for 40 years. What did that moment mean?

For a lot of us in economics and people in the financial press, that marked a sea change in popular thinking and the end of the reign of the pure free-market idea. Greenspan was admitting that the assumptions that underpinned his arguments for financial de-regulation had been proven wrong.

Do you think that the Tea Party movement–folks who are opposed to government spending–aren't actually in opposition to Keynes, but what you've been calling this "caricature of Keynes."

I do think there's a big element of that. There's nothing in Keynes' writing that suggested he would support, for instance, the government bailout of General Motors. Or the government bailing out big banks.

What would Keynes say about what we see today? If he wouldn't support bailouts of major banks and the auto industry, what do you think he would prescribe?

In his various writings over the last 20 years of his life, I think you can find him weighing, at some point, every possible kind of policy option in response to the Depression. He liked to put all the options on the table. He wasn't interested in nationalizing firms. It just wasn't part of his world. And likewise, although there were bank failures–I think in the first year that Roosevelt was in office there were 10,000 bank failures–he would not have thought about these questions in the same context that we do. Banks failing in his time would have had a very different impact on the whole system than Lehman Brothers or Goldman Sachs failing today. Banks then didn't have the size and impact of banks today.

So we did some things that he never dreamed of. We can't know exactly what he would've said, although I find it hard to imagine he would have seen a thing like bailing out General Motors as a legitimate use of fiscal policy to stimulate the economy. I do imagine that he would have been a big proponent of infrastructure spending: building new roads, fixing dilapidated bridges, building new schools.

The study and practice of economics has changed so much since Keynes's era– there are new models and techniques. How does he stay relevant?

I think what's happened in the last 15 years–and this has accelerated a lot in the past five years–is that behavioral economists have really come to the fore- front. These are people who take ideas from psychology and try to model economic behavior realistically, without assuming that people are perfectly rational. That's different from how economists have historically tried to picture them. We know, for instance, that people look at what other people are doing and mimic each other's behaviors, regardless of how smart the behavior is. So when a lot of people start investing in Internet stocks, a lot of other people follow. They don't say, "Gosh I think that's an unsustainable boom." They say, "Those prices are going up like crazy. I've got to get in on it, too." That behavior pushes the price higher until things get far beyond their true value and that causes a market collapse. So a lot of cutting edge behavioral economists are actually very supportive of the kinds of things that Keynes wrote about. One of his central arguments in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money was that financial markets easily develop bubbles, and when those bubbles collapse, it causes havoc elsewhere in the economy. Seventy-five years later, the behavioral economists are finally providing sound theoretical underpinnings for some of Keynes' insights.

Dan Morrell is a freelance writer based in Boston. He has written for The New York Times, Slate, Boston Magazine, and Fast Company.