The relentless sun beat down on the two-lane high-way where, a week before, a bus had been blown up, killing every man, woman, and child on board. The year was 1980, the place Uganda, a country ravaged by the decade-long reign of the now-deposed strongman Idi Amin. Bill Clarke and his two Habitat for Humanity companions were in a Jeep rolling down that same road toward the city of Gulu. There they would meet with government officials in the attempt to start Habitat in Uganda. The three men were discussing their frustrations, namely the Herculean bureaucratic obstacles they needed to overcome to build houses for the poor. Clarke wore simple clothes: a short-sleeve shirt, khaki pants and old cowboy boots that were comfortable in the African wilderness and only needing a quick shine to be appropriate for meeting an ambassador in the capital. Ensconced in the back seat, windows open, the flat African landscape passing by at 60 miles per hour, Clarke was determined to help the desperately poor people of Gulu, and he wasn’t going to let anything stop him. But in the following moments, “Stop!” was precisely what Clarke was screaming.

As the Jeep skidded to a halt, Clarke’s heart raced faster and faster. He braced himself for an explosion. Two military men—one brandishing an antitank gun similar to the one used to destroy the ill-fated bus seven days earlier—were charging up from under a bridge toward the Jeep. They had been yelling for the vehicle to stop before the bridge, and the driver had barely complied.

Bracing for death, Clarke watched the soldiers reach the Jeep. To his surprise, they spoke to the driver politely, asking him to deliver a message to men guarding the next bridge. Then they walked away. Clarke sat there in his seat, his body throbbing and shaking with tension. Once again, he managed to avoid dying in a land he only wanted to rescue.

Home Boy

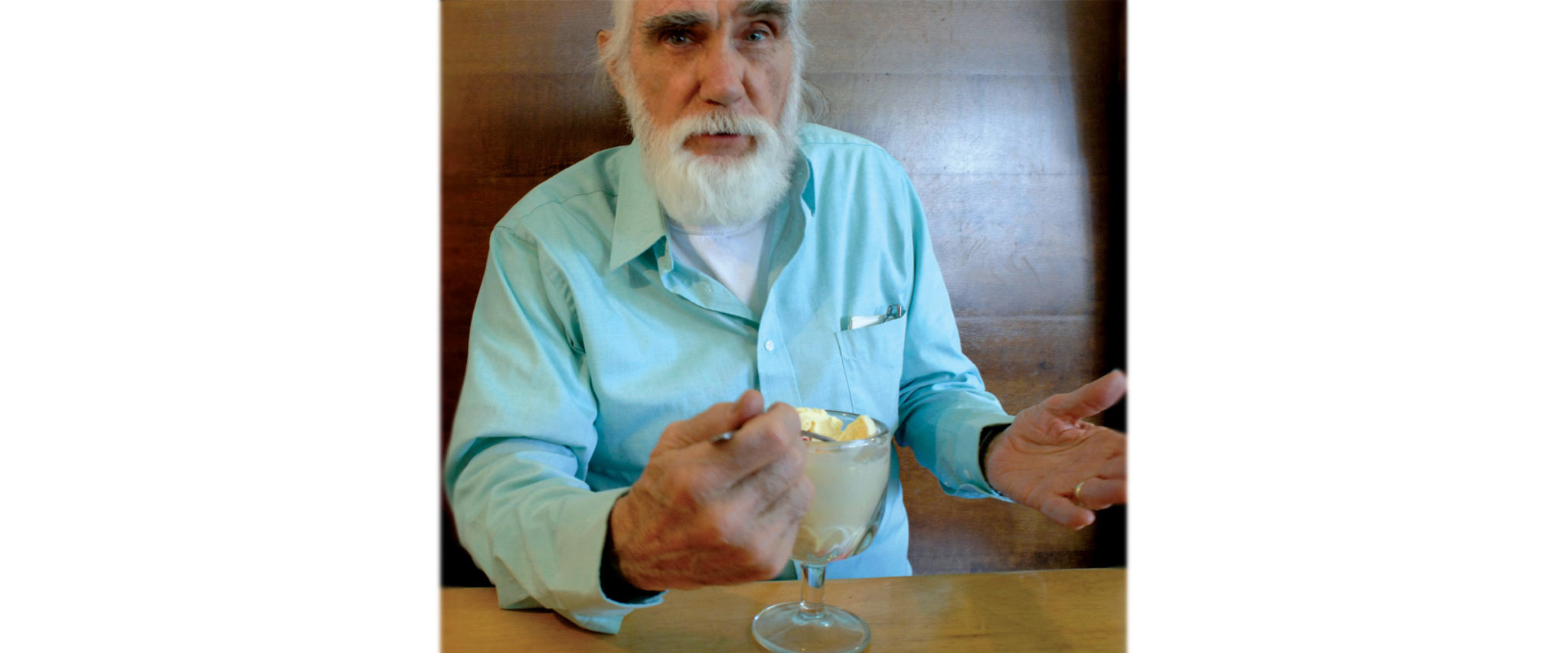

When you first meet Bill Clarke—who, among other accomplishments, played a notable part in the launching of Habitat for Humanity back in the 1970s—he seems to be one of those guys whose life begins and ends at the borders of his hometown of Canton. He’ll be glad to show you around. A short drive from his home on 22nd Street—only four blocks from the house he grew up in—is Hilscher-Clarke, the electrical engineering and contracting firm that Clarke inherited from his father and then ran for decades. Nearby is Christ Presbyterian Church, where he was baptized 76 years ago. And a long punt away is Canton’s most famous structure, the Pro Football Hall of Fame, which Clarke had a hand in building. His company wired the rotunda and Clarke himself chaired the committee that gathered the memorabilia for the exhibits.

Despite Canton’s grip on him, there are no borders in Bill Clarke’s world. In his 77 years on this planet, Clarke has ventured out time and time again to the places that many would rather forget than embrace. Each time, his mission has come down to a simple plan: When there’s a need that comes along, he is wont to say, I just try to see what I can do to help. He doesn’t worry about whether his impact will save thousands of lives or just one. You may not know whether you can solve anything, he’ll say, but if there’s one little thing you can do, you do it. It’s a simple plan, but it’s one that has allowed Clarke to accomplish a lot of good in the world. He’s comforted refugees in a crowded Croatian camp. He’s broken the law to save the lives of desperate Salvadorans. He’s persuaded the government of Thailand to aid a hungry hill tribe. He’s survived a gun in his belly, stuck there by a drunken government official in Zaire. And, in the dark of Zaire, when Clarke heard the lonely voice of a rudderless man calling out “Awa”—which roughly means “I am here”—he was moved to help in the best way he knew, by creating decent, sturdy housing and hope for that nation’s poor. “Everything I do, I do intently,” says Clarke, now silver-haired and somewhat mellowed, but no less determined. He embraces a mission with passion and then plows ahead until the job is done. It’s an attitude that started back in Canton, early in his life. In seventh grade, his body writhed in pain and he lay bedridden for an entire year, stricken with polio. He emerged with an unequivocal limp. Soon after, he tried out for the football team and ended up in the infirmary for a few days after the first practice, his muscles aching from the hits. But he bounced back, eventually dragging that troubled leg around the globe to help thousands in need find better lives. Today, Clarke is still as determined as a mule. Maybe as stubborn too. In many ways, he is driven by an appreciation of being born in the United States, where all citizens—despite certain social barriers and inequalities—are free to choose the path their life should follow. “We didn’t earn getting born here,” Clarke reflects. “We have to give. Otherwise, how do you live with yourself, just taking?”

Americus the Beautiful

Before Habitat, there was Koinonia Farm, a Christian community and working farm founded in the 1940s outside of Americus, Georgia, with the racism and poverty of the rural South as a back-drop. Even at the time of Clarke’s first encounter with Koinonia in the late 1960s, the community’s efforts to help their poor neighbors, whether they were white or black, was still a lightning rod. “You would go into Americus in those days, and you wouldn’t want people to know you were from Koinonia,” says Clarke. “They burnt our roadside stand down. Once in a while they’d shoot our windows. It was intense.” Koinonia workers were physically assaulted. While a friend of Clarke’s walked down the highway, a Coke bottle was hurled at his head.

Clarke’s involvement with Koinonia came about through his friendship with Millard Fuller, who, in 1968, founded Koinonia Partnership Housing, the pre-cursor to Habitat for Humanity. Clarke supported the work of Koinonia and provided leadership for its board at a time when the organization was foundering.

Clarke also supported Fuller, literally. Fuller and his family spent three years in Zaire doing mission work and planting the seeds for Habitat for Humanity International. When Fuller returned after spending so much time helping others, he found himself in desperate financial straits, with a family to feed and no money. Clarke covered the family’s expenses for an entire year so Fuller could turn his full attention toward Habitat.

At that time, Habitat tried to unite communities fractured by distrust and hatred between whites and blacks. In Americus, Habitat’s headquarters today, the group had endured as hostile a reception as Koinonia had. One Sunday morning, Clarke, a Presbyterian elder, was turned away from the Presbyterian church in Americus by local elders, who were upset that he would eat with and pray with black people. Clarke turned the other cheek.

Slowly, Habitat’s efforts made an impact. By 1980, a number of houses had been built in a town deeply divided by race, and a public meeting was slated to celebrate the project. Clarke remembers walking with his wife, Joan, out onto the balcony in the church with the largest white congregation in Americus and watching a scene they never could have dreamt unfold. Members of the black choir were singing. Blacks and whites on the altar talked together like old friends. “A few years before, if you were part of Habitat in Americus, you could be beaten up,” Clarke said. “We just started to weep.”

Today, well, you know the story. The nonprofit housing ministry has put up more than 200,000 houses around the world, providing more than one million people with affordable shelter—even in Gulu, where Clarke persuaded the government to welcome Habitat days after his scare by the bridge.

Habitat workers were physically assaulted. While a friend of Clarke’s walked down the highway, a Coke bottle was hurled at his head.

Out of the Frying Pan, Into the Fire

Clarke could have sat back, satisfied with himself for the work he has done in the United States and in Africa on behalf of Habitat for Humanity. But his simple plan wouldn’t allow for that. His next crusade began innocuously enough with a whitewater rafting trip in Arizona. One of his companions that day was John Fife, a minister in Arizona. Fife would open Clarke’s eyes to the plight of El Salvadoran refugees fleeing from a civil war.

Fife told Clarke that many refugees from El Salvador were making their way to Arizona. Fife was sheltering as many as he could, but other refugees were being arrested and sent back by the U.S. government, which supported El Salvador’s military regime. Those forced to return to their homeland were likely to be killed.

Clarke was stunned. He encouraged churches all over Ohio to defy U.S. immigration laws and offer sanctuary to fleeing Salvadorans. “I said, ‘I am an American, and this does not go,’” Clarke recalled. “We do not believe in these types of things.”

Others didn’t believe in them either, literally. His own congressman, Ralph Regula, senators and others dismissed Clarke’s stories. During many, many day trips to Washington, Clarke talked with congressional aides, religious lobbying firms, anyone, to make his case. When he finally convinced a top Regula aide by flying him to El Salvador, Regula sent a letter to congressional colleagues appealing for their help. Eventually, the bill to grant temporary asylum that Clarke had lobbied for was passed.

Yet his work wasn’t finished. Four or five Salvadorans arrived in Canton, having heard of Clarke’s support. A woman whose husband had been killed by death squads appeared at his door, but her two children were back in El Salvador, hiding with their grandmother.

Clarke’s wife, Joan, insisted he had to get those kids. Clarke called Elliott Abrams, then assistant secretary of state for Inter-American Affairs in the Reagan Administration. Abrams said there was no way to bring the children to the United States, so Clarke boarded an airplane to El Salvador, found the grandmother, and gave her contact information for her daughter to help the kids get out of there through the underground network.

His attention now focused squarely on the displaced, Clarke took on the burden of aiding refugees in other countries. In 1986, Clarke was named chairman of Refugees International. During his decade-long tenure, the average annual budget for the non-profit group hovered around $250,000. Some people can’t run a modest business on that, and Clarke was supposed to guide a worldwide organization.

He traveled to Washington to promote the cause of refugees among U.S. officials. He visited Thailand and persuaded officials there to aid Hmong hill tribes languishing at the Thai-Laos border. He traveled to Croatia in 1992, as war raged, and was horrified by what he saw—half-starved men emerging from torture camps, women who had been raped by Serbs in an attempt to procreate and extend the Serbian race. He pleaded in a letter to President George H.W. Bush to welcome these refugees to the United States, asking for 6,000 to be let in immediately. Amidst all this, and 30 miles from the war’s front line, he helped put together an interfaith service of Muslims, Jews, and Christians to try to find common ground in the besieged land.

By the time Clarke left Refugees International in 1996, his dedication had made up for its cash shortfall. As Shep Lowman—who became executive director of the organization shortly after Clarke was named its chair—recalls, “Well, Refugees International might not have made it, but Bill just sort of held my hand. I would always pay everybody else, and I couldn’t always pay my own salary, at least not on time. Bill didn’t have deep pockets like some of our funders, but he had pockets he was willing to dig into. And he kept us going during that period.” Dawn Calabia, a commissioner at the United Nations, wrote him that his guidance and commitment amid rocky finances had ensured the survival of the humanitarian organization.

Yes, Bill Clarke can seem like an unstoppable force for good. But this story could have been as nondescript as a barstool because at an earlier point, his life was in tatters, and he didn’t know how to fix it.

The Transformation

Soon after Clarke crawled out from a year of bed-ridden inertia, he joined what, back in the day, was known as a bad crowd. Already living the mantra that everything he does he does intently, he drank hard—so hard that his parents shipped him to a prep school in Detroit where, he recalls, “I became a polite drunk instead of a sloppy drunk.” Denison admitted him and the college’s new Delta Upsilon chapter made him a charter member (although it was the only fraternity that would accept him, such had his reputation preceded him). After spending a good bit of time at a Newark bar and ushering at a Granville Baptist church while nursing hangovers, he reluctantly left Denison after his sophomore year because the engineering course he had to take as a junior to qualify for a program at MIT was only offered every two years—the wrong years for Clarke.

A year later, having lost a taste for engineering, he enrolled at Northwestern University, where he earned a bachelor’s in business administration. It was in Chicago that he met Joan, the woman he would marry. In 1953, after two years with AC Nielsen company, Clarke was persuaded to move back to Canton; his father was failing as Parkinson’s disease took its toll, and Clarke was regarded as the eventual heir to the company.

For their first seven years in Canton, the Clarkes were busy, Joan with raising their daughters and Bill with juggling family, business, church, lots of Jaycees youth projects, and lots of late nights in Canton bars (where planning for his many activities often occurred). And the drinking was getting worse. His wife had become a mere acquaintance; the topic of divorce had been broached.

Clarke appeared to be a model citizen, developing a sense of civic duty and working with area youth. All throughout, he was an active member of his church, even serving as a deacon, elder, and head of the men’s council—although without believing in the church’s central tenet, that Jesus is God. But as his life slowly unraveled, Clarke finally bared his frustrations about his life to another deacon. Somehow during this talk—call it divine intercession, if you will—a revelation hit Clarke. He walked away a believer, his outlook transformed. He joined a group studying spiritual healing. Yet he still “I kind of confessed to her who I really was: a scared little kid really,” Clarke said. “We got down on our knees, and we committed this marriage to Christ. What I’m telling you is that we got up off our knees and we were deeply in love again.” didn’t tell Joan of his revelation.

Clarke was told he had to commit his life to Christ in front of witnesses, and he decided to do just that during a Faith at Work conference in upstate New York. Joan had gone with him, but he wasn’t counting on her being a witness until the group leader he intended to talk to became unavailable. Having no choice, he asked Joan and his pain came gushing out.

Within a month of his change, Clarke gave up drinking, save for a glass of wine here and there. True, business has suffered for Canton bartenders since Clarke took control of his life, but the declining Ohio city has reaped many other benefits.

A Good Neighbor

As Canton has struggled in recent decades—hemorrhaging jobs and residents, casting a quarter of the population into poverty—Clarke has been a constant in town. On several occasions, after he became involved in Habitat for Humanity, he seriously considered moving to Zaire—he even checked into schools for the kids—but somehow determined each time that was not part of God’s plan for him. A few years ago, he and Joan built a house near Flagstaff, Ariz., and settled in to retire. But only six months passed before the homesick couple hauled their belongings back east.

Today, four years after he last helped the troubled in foreign lands (following a visit to Nicaragua for Habitat, he developed post-polio syndrome and now can barely walk a block), Clarke champions the youth of Canton, buoyed in large part by his Christian faith.

Clarke says four out of every five students in the Canton public school system come from poor families. So he’s trying to persuade two schools to launch a pilot program this fall, through which each kindergarten student will be assigned a mentor for at least six years. Clarke mentored five fifth-graders last year. “I said to one kid, ‘I really like you.’ He said, ‘You do?’ The fact someone really liked him blew him away.”

Clarke’s history embracing causes to benefit youth dates back to his return to Canton. He started by sponsoring teenage boys who were in trouble with the law, getting them off the streets and involved in groups like the YMCA. He worked with the Jaycees to open up a downtown social club for teens. He started a branch of Young Life, a youth ministry. As the board chair for the local YMCA branch, he introduced a summer job program for youths and the first public daycare center in Canton for poor working mothers.

He has done so much to help the people of Canton and the people of the world, it’s a wonder he was able to manage his professional life. When he was called home in 1953, not only was the health of his father faltering, but so was that of Hilscher-Clarke, the firm his father founded. At 32, when Clarke was named vice president, secretary, treasurer and a board member of Hilscher-Clarke, it was losing money rapidly. Today, the firm is prosperous, boasting $20 million in revenue annually.

But the Summit neighborhood where it is head-quartered has become the most dangerous in town. About six years ago, Clarke rounded up a few friends and started a non-profit group to rehabilitate Summit houses. Today, he completes his tour of Canton by driving around this crumbling neighborhood in his Chevy Tahoe. Pointing out a small housing project that had just been exposed on the front page of the Canton daily newspaper for its drugs and violence, Clarke contemplates what his hometown was—and what it could be. “I used to come downtown on the bus as a kid to the movies, and it was perfectly safe,” he reminisces. “This used to be such a wonderful place, Canton. We’re trying to get it back to that.”

Clarke retired from running Hilscher-Clarke in the 1990s, and he eventually sold the lion’s share of his stock back to the employees. He could easily build an Arizona abode again with Joan and this time stay put. No more heartbreak seeing Canton’s youth flail in an uncaring, spiraling town. Invite the four daughters and the host of grandkids and captivate them with stories about wild days in crazy lands, facing danger in order to do right by his global neighbors.

Why doesn’t he simply reflect on the immense good he’s already done in the world and take a break from saving it? Because, quite simply, he can’t abandon his simple plan. There are needs. Clarke sees them, and after decades of taking on causes around the world and in his back yard, of avoiding destruction by his own hands and by the hands of others, and of sensing reminders of just how lucky he is, he can only shrug and refer back to the plan. “I just try to see what I can do to help,” he echoes. “You may not know whether you can solve anything, but if there’s one little thing you can do, you do it.”