What did the investing sector look like in the 1980s?

When I started, we were an industry selling access and information. You had to have access to market intelligence others didn’t and advice on how to tap the markets.

Then the internet was born, and there was a moment in time where investment banking went completely out of business. But a second later, it came back full force, because the internet was democratic; it gave information to anybody who wanted it. And almost instantaneously there was too much information. Our jobs changed. We were no longer the only ones with the information—but we were the only ones that knew how to sift through it all.

Recently, we’ve seen a further democratization of the investment markets.

Five years ago, if you were a Denison student and you wanted to invest in real estate, you couldn’t. You needed hundreds of thousands of dollars, and that’s if you were lucky enough to have access to that particular building on Park Avenue, for example. Now, you can go online with any number of apps and buy a brick in that building because of tokenization. We’ve seen this with the Robinhood app, too, for stocks. And we’ve seen the growth of SPACs [special purpose acquisition companies], which allows anyone to invest in a company long before they are ready for an IPO. There is no longer a barrier to entry to access any asset class. It’s changing the game completely.

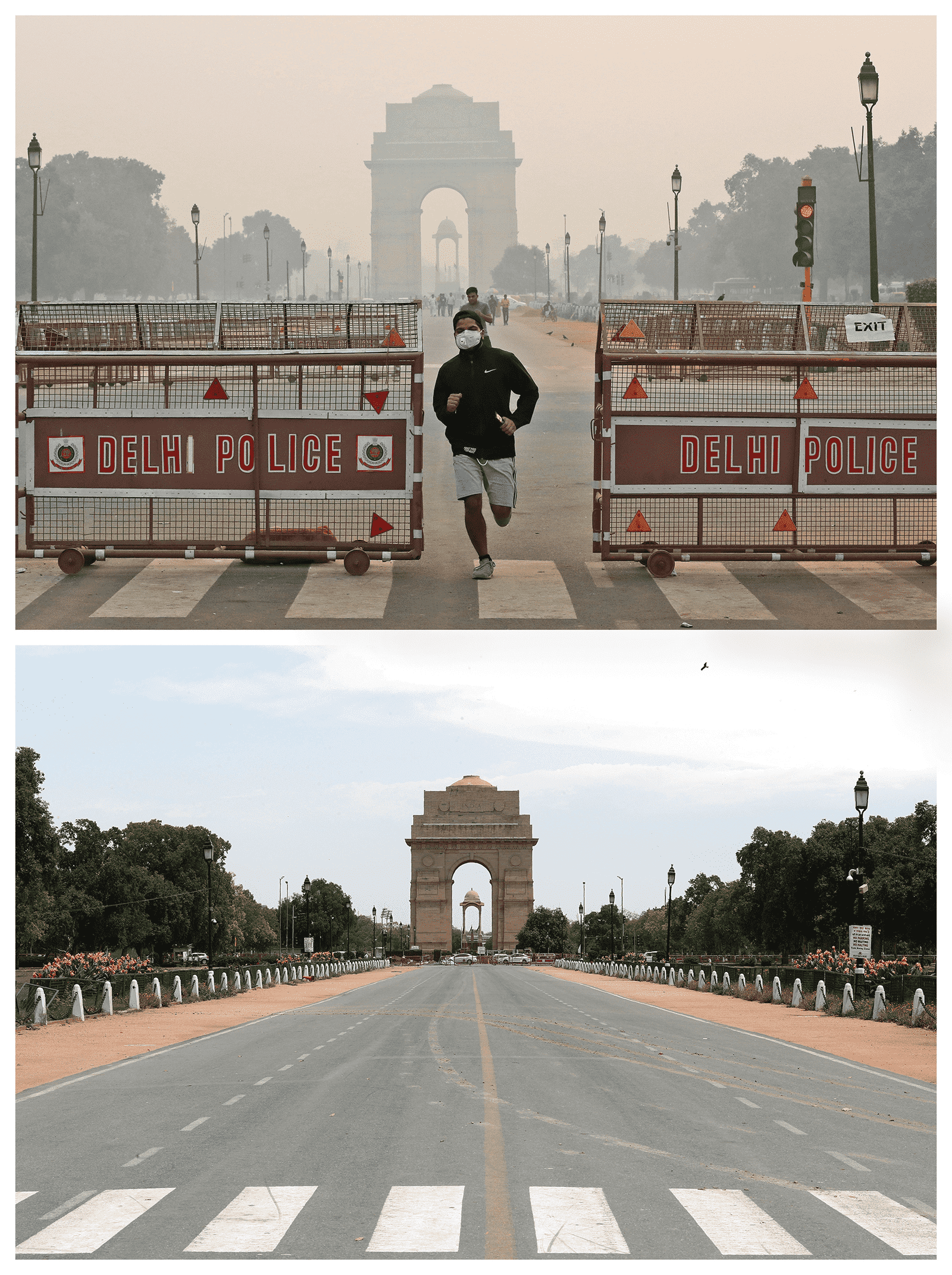

Has the pandemic changed investor priorities?

Oh my, yes. We all got an awareness wake-up call. From a planet perspective, everybody has seen that Google Maps image of a major metropolitan area in China that was completely smog at the beginning of the pandemic. And then, six months later, it was beautiful, green rolling hills. That’s what happens if you don’t have to drive somewhere every day.

On the social side, regulators and public opinion demanded, for example, that companies not pay dividends to their shareholders if it meant they were going to have to lay people off. Industries have stopped layoffs on a global basis at the expense of shareholders. That’s never happened before.

The constituency for corporations around the globe is not just their shareholders anymore. It’s about the greater good. We all have a responsibility to the planet. We all have a responsibility to our communities. The pandemic has changed the dynamic considerably, and I think that will stay with us for a long time.

Just five years ago, you were skeptical about the potential of ESG—environmental, social, and governance—investing.

I got it wrong, and I am thrilled about that. I thought that clients would only want to invest in ESG if it didn’t cost them any more, and it’s expensive to set up these funds and do the data analysis on sustainability. But that’s a myth—it doesn’t need to cost you money to invest in a sustainable and responsible manner, and it’s not just about financial returns; we have the ability to track other outcomes for our clients. I also had the wrong impression that these portfolios had to exclude certain sectors, that you couldn’t have an energy-efficient, low-carbon fund that includes an oil and gas company. That’s not true. We can help companies work toward sustainable goals.

We’ve seen interest in ESG come from the grassroots around the world. If you are an institutional pension fund, and you don’t care about ESG, but all your pensioners are starting to say, “I want a sustainable choice in my investments and my 401k,” you start to pay attention. Governance—how well a company is managed—is something investors have always taken into consideration. What is changing?

“How strong is the management? How are their audit findings? Are they facing any regulatory fines?” These are all fairly obvious questions that have been a part of investing forever. But now the interest is shifting to things like diversity, equity and inclusion, and labor practices. “Do you have diversity in senior management? Do your employees own shares in your company?” The definition of “good governance” is evolving.

When did environmental considerations become important to investors?

UBS is about to celebrate the 25th anniversary of our first global sustainable equity fund, which focused on the environment and the effects of a company’s footprint. It’s now everywhere, and the investing world is focused on those areas where there is the most data available. You’ll see more financial products and more demand from investors as we have better ways to measure a wider range of environmental impacts.

Why has the S—the societal impacts—of ESG been the slowest to rise to prominence?

Because the “S” was very hard to measure, people were quite dismissive of it. Companies don’t report the gender makeup of their workforce publicly, for instance. In the United States, they report this data to the federal government. Why not make it available to the public, to investors? If we can’t measure it, we can’t improve upon it.

Now we’re seeing the same grassroots outcry we saw around the environment on social issues: “How many people of color do you have in your management ranks or on your board of directors? How many women? And do they stay for a long time? What’s your retention rate?” There is a growing effort to get that data. Then you can start deciding what types of changes can actually drive better performance at a company.

"It’s going to cost money to invest in some of these things. . . Once built, then we can prove the point that there are returns on those investments."

Do we need to worry about “greenwashing”—companies that want to appear to be doing the right thing without making a real commitment to change?

It’s very dangerous to try to put something over on the market these days. There’s enough information and transparency that you are going to get called out for it if you are not making real changes. Three years ago, if an investor asked if your company was ESG-friendly, you could say yes, and that was all they needed to hear. Now everybody’s smarter. When you say, “Yes, we’re environmentally friendly,” they say, “Where’s the proof?”

Will we see this trend toward ESG investing continue post-pandemic?

We know that these things matter. But in the face of the mighty dollar, how long will they matter? That will depend on the grassroots. Right now, there isn’t an annual shareholder meeting that doesn’t have people saying, “Where do you stand on ESG? Where do you stand on diversity?”

If they stop asking those questions and instead ask, “Well, you’ve spent all this money on diversity, what about my share price? Why isn’t it up?” you’ll see that shift back to the old mentality.

We need to get through the phase where it’s going to cost money to invest in some of these things—in training programs, development plans, technology for work-from-home. Once built, then we can prove the point that there are returns on those investments. But it’s getting them built in the first place that’s the trick.

People only have to keep up the pressure long enough for companies to adapt to these changes, to embed them in our cultures, and then we will have really moved the needle, sustainably, for the long haul. We know this is better business.

Is it the responsibility of the asset management industry to champion sustainable and socially conscious investment?

Our role is to advise, educate, and raise awareness. It is not my job to impose my personal values or UBS’s corporate values on my clients. But our fiduciary responsibility requires that we understand the risks for our client’s portfolio, and climate risk is real. There is no question about it. There’s real, physical risks attached to that. There is also brand equity risk, if a company is going to take an unpopular social position.

It is not for me to tell my clients where to spend their money or what cause to support. I always point out there are 17 sustainable development goals [established by the United Nations], and some of them can be contradictory. I need to give my clients choices, and they get to choose.