When James W. Toy ’51 enrolled at Denison in 1947, the gay community on campus hardly warranted the name.

“There was no such thing,” Toy says. “Or if there was, it was underground, and I was unaware of it.” Then again, at the time, Toy, who grew up in Granville, wasn’t even aware that he was gay.

“I didn’t know the word ‘gay.’ I didn’t know the term ‘sexual orientation,’” Toy says, adding that such things were not discussed in the Granville of his youth. Toy had the added distinction of being biracial—his father was Chinese, his mother white—and though he found a home on campus in the American Commons Club, a fraternity that was open to all regardless of color, race, or creed, it would be many years before he would discover his sexual orientation, let alone find others who shared it. “I thought there was no one like me, and I would remain isolated for my entire life,” he says. “I had no concept of either being in the closet, or coming out.”

It’s hard to imagine what Jim Toy would make of Taylor Klassman’s experience of life at Denison in the new millennium. Klassman ’13 is president of Outlook, the college’s gay-straight alliance, an organization whose purview encompasses all things GBLTQA. The acronym stands for gay, bisexual, lesbian, transgender, questioning, and allied—the latter being the contemporary term for straight friends and supporters. Though Klassman describes isolated incidents of homophobia on campus—“a lot of that happens, unfortunately, between friends, or in roommate situations”—she paints a picture of a school where most gay and lesbian students are out of the closet, and where older LGBT alumni find it difficult to believe that things could have changed quite so much. This raises an obvious question: How exactly did Denison get from there to here?

Hansell believed that a liberal arts education had something to do with being accepted for who you were.

The story of how Denison evolved from the college of Jim Toy’s recollection to the one that Taylor Klassman currently inhabits is a complicated one.

It occurred in stages, spurred on by broad societal changes, and also by circumstances and personalities unique to the Hill (a closeted Jewish fraternity brother, for example, and an English professor who went through two husbands before finding a wife). “It’s kind of a hidden story that’s not even well known to a lot of gay and lesbian alums,” says Jeff Masten ’86, a current Denison board member who helped found the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Alumni Association (GBLTAA).

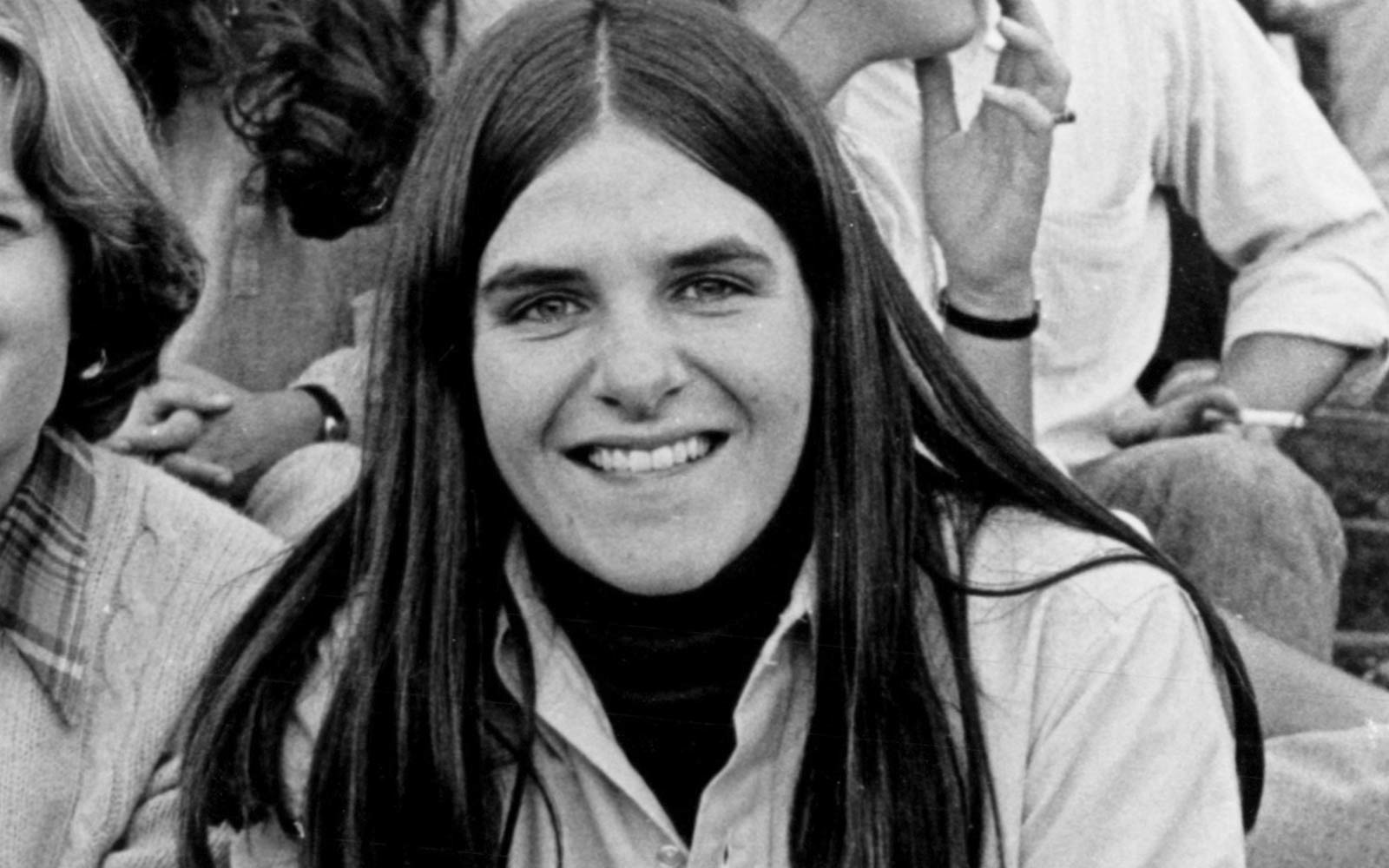

That story begins in the early 1970s, a period of social and political ferment, and of what Dean Hansell ’74 calls “campus upheaval.” When Hansell, now an attorney in Los Angeles and a former Denison trustee, arrived on campus, students were protesting the Vietnam War, and a campuswide strike recently had been staged in support of black student demands for a greater African-American presence at the college. On the LGBT front, the American Psychological Association still characterized homosexuality as a mental disorder, and sexual activity between people of the same gender remained a crime in many states, including Ohio. On the other hand, a few gay student organizations had been established at universities like Columbia, Cornell, and NYU; the Stonewall riots of 1969 had set the modern gay rights movement in motion; and Jim Toy was about to co-found the Human Sexuality Office at the University of Michigan, the first staff office dedicated to addressing sexual orientation concerns at an American college or university. Nonetheless, Hansell, who would later help found the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), a national media advocacy and anti-defamation group, says that there was “really nothing” going on in terms of organized LGBT activity at Denison—a situation he sought to remedy.

Hansell was in an unusual position. Both Jewish and gay, he belonged to two campus minority groups that were largely invisible. He also believed that liberal arts education had something to do with being accepted for who you were. By the end of his freshman year, Hansell had already helped to establish a faculty/student Jewish organization, but organizing the LGBT community was a lot trickier. Student life was dominated by the Greek societies, and in particular by the fraternities—institutions that have for much of their history modeled what might diplomatically be called conservative gender norms.

It wasn’t until Hansell was elected Denison’s student body president in 1972 that he felt he could take action. Feeling a bit of trepidation but also “a sense that this was the right thing to do, and probably an important thing to do, as well,” Hansell placed a flier in every student mailbox listing all of the college’s 30-some extracurricular clubs, buried a gay student organization in the middle, and invited all interested parties to submit their mailbox numbers rather than their names. Then he booked a conference room in the basement of the library under the guise of convening a “faculty evaluation project” and held a secret meeting. “It was the beginning of organized gay life on campus,” says Hansell.

It happened in Curtis Dining Hall in the spring of 1984.

Michael Dowling ’85 was having dinner with some friends when a couple of straight students bumped into a gay student. The gay student reacted, and a fight ensued. Activity came to a halt as an entire cafeteria full of Denisonians watched the straight men deliver a beating while shouting homophobic slurs. “At that point, several of us said, ‘This can’t go on anymore,’” says Dowling, who now works as a healthcare executive in New York City. “We were afraid.”

Dowling and three other students published a manifesto in the Bullsheet, a daily student opinion page, decrying the violence and establishing a gay-straight alliance, Gay and Lesbian Advocates at Denison (GLAD). That same year, GLAD introduced the first campuswide gay awareness event: Blue Jeans Day, during which all were invited to wear blue jeans to show their support for gay and lesbian students and faculty. By 1987, Blue Jeans Day had expanded into a Gay Awareness Week.

As Masten wrote in an essay that was published in this magazine in 1992, his own time at Denison had been characterized by a feeling of “doubleness.”

“I was both ‘at home’ and displaced—very much a part of the place in some ways, and often at odds with some of the people who also called it home,” he wrote. “I remember with acute discomfort the experience of feeling out-of-place—misplaced as a gay person in a community organized around events like fraternity parties and formals that either unintentionally or deliberately marginalize gay people, and displaced from other gay students who, like me, remained invisible.”

At the same time, gay and lesbian faculty had begun to step out of the shadows. At a faculty meeting in the mid-1980s, music professor Lee Bostian came out to his colleagues and instantly transformed himself into a mentor and role model for gay students. “Here was somebody who had been in a heterosexual marriage for many years, who had five children, and who had been a part of the community—and he came out with an activist passion,” says Masten, who credits Bostian with helping lay the groundwork for the GLBTAA. Bostian’s revelation encouraged other gay faculty and students to become more visible, and led to off-campus meetings between gay students and faculty and their straight allies. “So much never would have happened if he hadn’t done what he did,” Woodyard says.

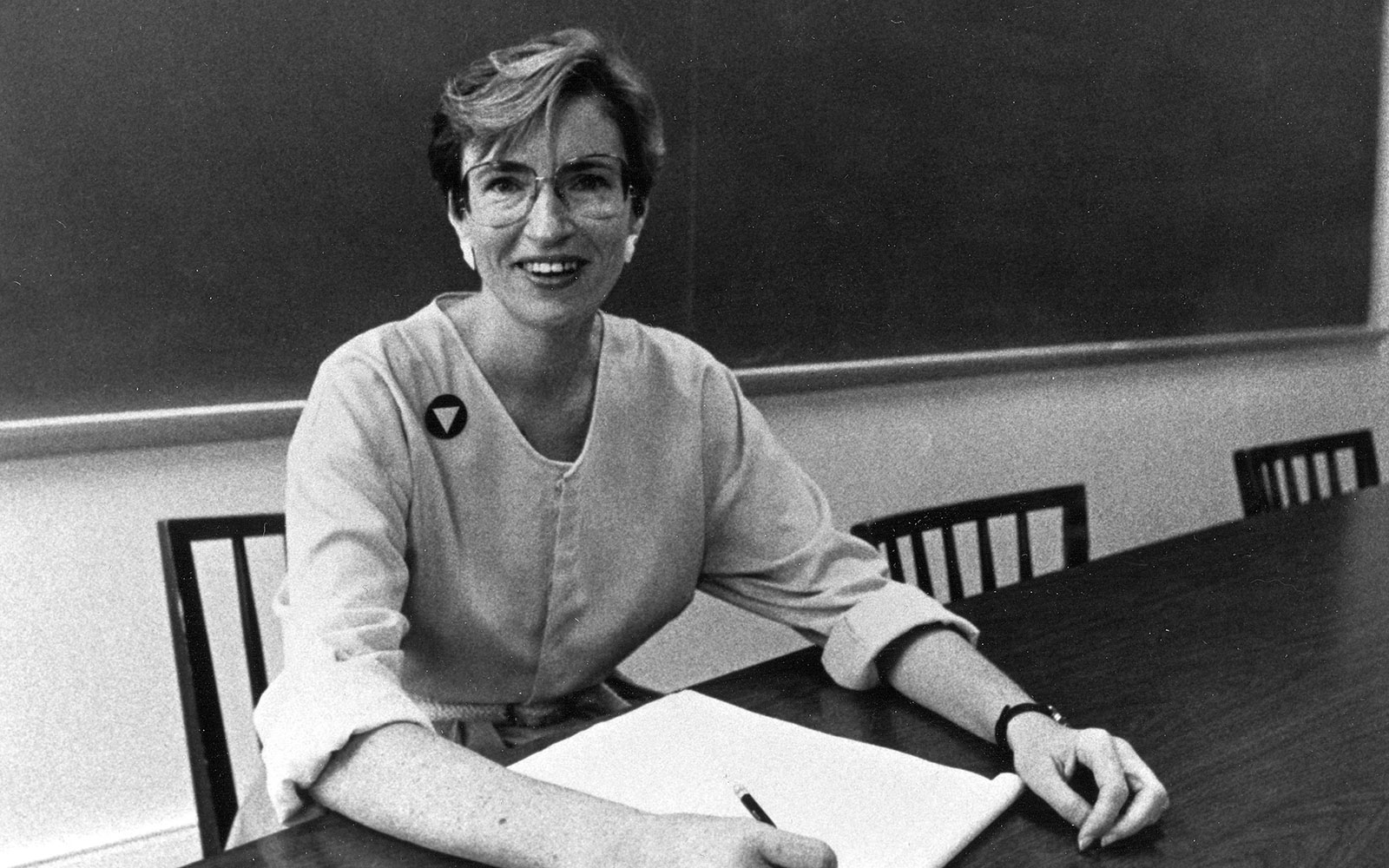

Much the same might be said of Anne Shaver, an English professor who had been straight when she first arrived on campus in 1973, or as she says, “I wasn’t gay—I was just divorced!” It wasn’t until 1986, after her second husband left her widowed, that Shaver fell in love with her current spouse, the English scholar Susanne Woods.

Like Bostian, Shaver became an informal advisor to students who were sorting out their own sexual orientations. Her influence only grew when, in 1993, she offered the first course in gay and lesbian studies at the college. When initially asked to develop one, she’d laughed: “You think any freshmen are going to sign up for a course like that?” But when “Partnerships and Politics: the Literature of Homosexuality in America” debuted, Shaver says, 70 students tried to sign up for 25 spaces. Victoria Larson Klein ’97 was among the first to enroll; as she recalls, most of the students who signed up “didn’t even know there was a gay literature.” Shaver wound up teaching two sections, and in 2000, the same year she retired, she, along with Marci McCaulay in psychology and women’s studies (now director of Denison’s Center for Women and Gender Action) and Chuck Morris in communication (now faculty at Syracuse University), made the first proposal for a queer studies program.

The creation of the GLBTAA (or the GLBAA, as it was originally known) further contributed to what Denison board member Kim Cromwell ’81 describes as “a kind of thawing” in the campus environment. In 1987, Bostian invited Cromwell, Masten, and others to join a gay and lesbian alumni panel to discuss their experiences on campus and beyond. More panels ensued, and in 1989, some of the participants met with campus allies in a lab in the biology building to form an alumni group. From the outset, the association aimed to make the campus a safer and more welcoming place for current LGBT students, and to help LGBT alumni reconnect with a college from which many felt alienated.

Cromwell, who now works as an organizational and leadership consultant, recalls that it took a couple of years for the office of alumni relations to get comfortable with the idea of posting a notice in Denison Magazine inviting alumni to contact her or other members of the fledgling group. When it did, a flood of letters quickly followed, some supportive, others frankly homophobic. Not surprisingly, several students—who also had been invited to the gathering—initially asked that meetings be held off campus, for fear of being outed. But then-President Michele Myers made it clear that she stood with the association, and it soon became part of the scenery, with Homecoming gatherings on campus, organized by Tom King ’69 and Rick Carson ’65, as well as annual “campus climate” discussions in which faculty, administrators, students, and alumni could talk about matters of interest or concern, from queer curriculum offerings to same-sex spousal benefits for college employees.

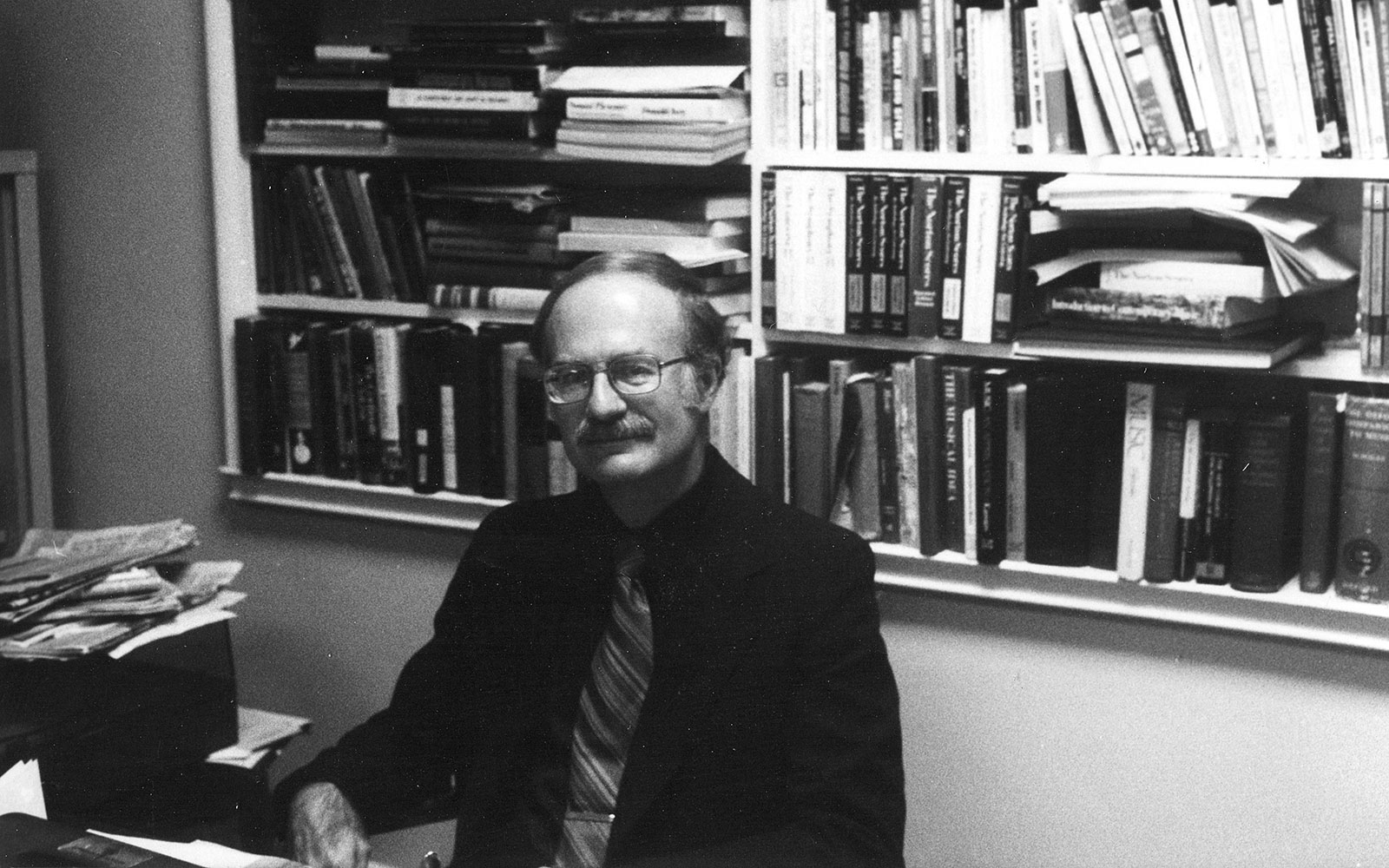

It bears noting that Hansell was in the closet at the time, and indeed remained there for the duration of his college career. As a student in the 1970s, he simply didn’t feel that he could effect change as an avowedly gay student. “The campus was a lot more conservative at the time, and the idea of gay activism had not really swept onto the college scene,” Hansell says. More to the point, he doubts anyone would have signed up for the organization had he come out, so great was the social stigma attached to being gay. After all, this was an era when LGBT students met either furtively off campus, or in safe havens established by sympathetic faculty like Professor of Religion David Woodyard ’54, who allowed gay and lesbian students to gather in the basement of Swasey.

At around the same time that Hansell was circulating his flier, the college also began offering its first courses in women’s studies, providing LGBT students with an intellectual framework for thinking about gender and sexuality, and creating what Masten, now a professor of English and gender and sexuality studies at Northwestern University, describes as “an intellectual context in which we could talk about issues that were central to our own identity.” Like Toy, Masten grew up in “conservative small-town Ohio” and had “no vocabulary to talk about gay issues,” yet with the support of both gay and straight faculty, he soon began to articulate his sexual orientation.

If the 1970s saw the first glimmers of progress, the 1980s proved to be a watershed. Off campus, the AIDS epidemic did much to raise awareness of LGBT issues, while prompting a surge in gay activism. On campus, the Greek influence remained strong, most LGBT students and faculty were still in the closet, and meetings still tended to be informal and private, if not clandestine. But that would soon change.

The Study of Difference

In 2008, the future of queer studies at Denison was in question.

Limited to one or two courses, Queer Studies was a concentration without concentrators, few faculty members felt qualified to teach the subject, and there was talk of dropping it from the curriculum. With the support of Provost Brad Bateman, however, Professor of Economics Robin Bartlett stepped in as director and developed a plan to train 16 instructors from various departments to teach two core courses and a broad range of electives. Today, 30 professors from 15 departments contribute to the concentration, with three concentrators having graduated last year, seven set to graduate in May, and eight more to graduate next year. Drawing on postmodern literary criticism, as well as gay and lesbian studies, queer studies can itself seem as abstruse as particle physics to those who have never read Michel Foucault or Jacques Derrida, but as Bartlett explains, the field is basically concerned with examining just about everything—history and politics, science and religion, music and dance—from the queer perspective.

The very word “queer,” Bartlett says, is about power and privilege, about defining who’s in and who’s out: “You could be black in some societies and be queer, or you could be white in Kenya and be queer, because you’re not in the norm.” (It should be noted that some may consider the term “queer” derogatory, but it has been reclaimed by the gay community and is often used by academics, says Bartlett, to describe whatever is deemed to fall outside the norm or majority.)

While it is anchored in considerations of sex and gender, queer studies is by no means relevant only to members of the LGBT community, nor is it always about them. Those who fall within the majority—including the archetypal “average straight white male”—can also get a lot out of it, such as a better understanding of how even the most normative gender roles (the breadwinner, the stoic) entail a variety of hidden costs.

Students majoring in a variety of fields can concentrate, or focus, in queer studies. They choose from a long list of electives that address the relationship between the normative and the transgressive, then apply what they have learned in a senior seminar in which they study a topic of their own choosing through a queer lens. It’s a model that encourages fresh thinking from both students and faculty members. The primary impetus behind queer studies—i.e., to question fundamental assumptions—is, as Bartlett puts it, “what we should be doing in the liberal arts, anyway.”

Alexander Gelfand is a writer in New York. His work has appeared in The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and The Economist.

In a sense, all of these changes reflected a broader shift in American attitudes toward sexual orientation that began in earnest in the 1980s and gathered momentum through the 1990s.

In 1993, for example, after 20 years of trying, Jim Toy and other activists finally succeeded in bringing about the amendment of the University of Michigan’s nondiscrimination bylaw to include sexual orientation as a protected category; closer to home, First Baptist Church of Granville was ousted from the Columbus Baptist Association in 1995 for welcoming gay and lesbian congregants. Internal changes at the college also helped spur things along: the same year that First Baptist was “disfellowshipped,” to use the rather cumbersome language of the church, the Denison board of trustees, who were addressing a number of complex social and residential issues, decided to make the college’s fraternities nonresidential. The move began to break the organizations’ hold on campus social life. Klein, who was co-chair of Outlook at the time, remembers addressing the board and describing how Greek culture had marginalized and excluded gay and lesbian students.

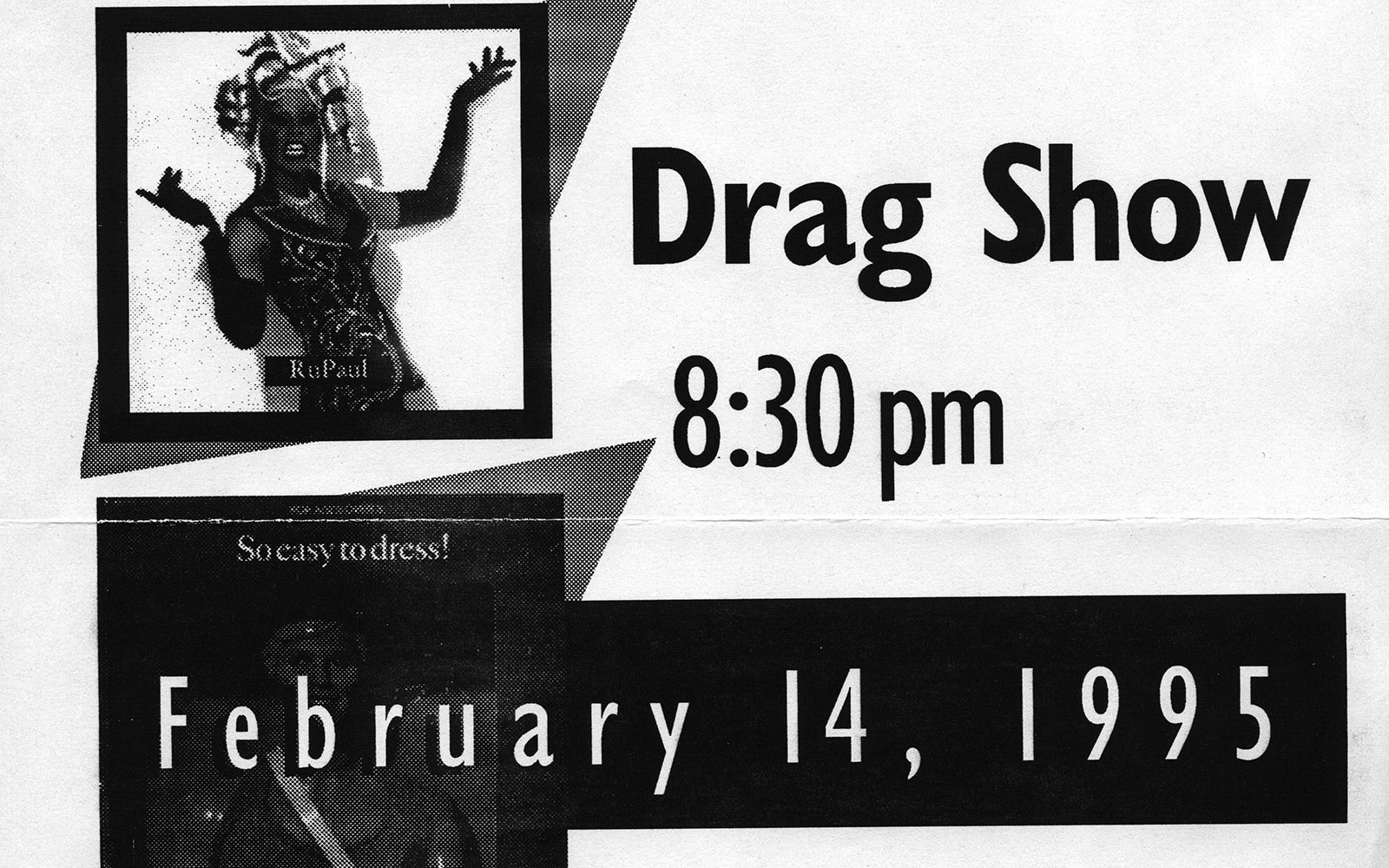

Klein represented a new generation of LGBT students who were more comfortable with their sexual orientation and less inclined to be quiet about it. “I feel like we sort of burst onto the scene as big, loud, out gay people,” she says. “It wasn’t hostile; it was more playful and happy.” Among other things, Klein and her fellow loud, out students bestowed two new traditions upon the college: an annual drag show at the student union, and the act of “chalking the quad,” or writing supportive messages on the sidewalks of the academic quad during National Coming Out Week in October.

Those messages have not gone unnoticed. Lisa Schilansky ’09 saw them while visiting campus as a prospective student, and recalls thinking, “This is so gay-friendly. I have to come here.” Schilansky, who grew up in “a very homophobic town” in upstate New York and had contemplated suicide after being outed in middle school, found herself gradually coming out to the campus community over the course of her time at Denison. Now a licensed social worker, Schilansky helped expand the college’s Safe Zone program to include training for confidential faculty and staff advisors. The Safe Zone Program identifies individuals on campus who are committed to providing a safe and supportive environment for LGBT students. (Similar programs began popping up on campuses across the country in the early ’90s under a variety of names: Safe Space, Safe Harbor, Safe On Campus.)

As the ongoing national debate over gay marriage demonstrates, it would be naïve to suggest that all traces of sexual intolerance have been extinguished with the arrival of the millennial generation. Schilansky, for example, believes that her Safe Zone initiative drew momentum from the events of 2007, during which a series of public conversations concerning prejudice on campus revealed a string of homophobic incidents. As a self-identified bisexual in a country where not all states prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, she harbors fears about possible job discrimination. “It’s ridiculous that I have to worry about this in 2013,” Schilansky says.

Yet it does seem that the steady progress of the past several decades has been radically accelerated of late. Masten traces recent on-campus gains to an increased commitment to promoting diversity in general, and to the notion, still relatively new, that inclusion of LGBT students can and should be part of a broader effort to embrace difference of all kinds, thereby improving the Denison experience for all students—regardless of whom they may love. But he also sees the growing acceptance of LGBT people on campus as a reflection of Denison’s longstanding values. “There’s always been a real commitment to community at this place,” he says.

Whatever the reason, the results are striking. Schilansky recalls how astonished she was as a senior hearing first-year students talk about being “completely out,” something she couldn’t have imagined for herself just a few years earlier. Meanwhile, Taylor Klassman believes that tolerance of gays and lesbians is literally increasing on an annual basis as, with each incoming class, Denison gets an infusion of young people for whom sexual orientation is simply a non-issue. Today, says Klassman, “two women or two men can walk around campus as a couple and not be gawked at”—something that may not have been the case even five years ago, and that would have been almost unimaginable in the not-so-distant past.

Some older LGBT alumni are among those who find the changes almost unbelievable. “I think sometimes alumni anticipate that we’ll come to reunion and talk about current instances of hate and the barriers that we still have to break through,” says Klassman, who adds that alumni from earlier eras can find it “unsettling” to learn that so many of those barriers have already come down. But come down they have.

The Study of Difference

In 2008, the future of queer studies at Denison was in question.

Limited to one or two courses, Queer Studies was a concentration without concentrators, few faculty members felt qualified to teach the subject, and there was talk of dropping it from the curriculum. With the support of Provost Brad Bateman, however, Professor of Economics Robin Bartlett stepped in as director and developed a plan to train 16 instructors from various departments to teach two core courses and a broad range of electives. Today, 30 professors from 15 departments contribute to the concentration, with three concentrators having graduated last year, seven set to graduate in May, and eight more to graduate next year. Drawing on postmodern literary criticism, as well as gay and lesbian studies, queer studies can itself seem as abstruse as particle physics to those who have never read Michel Foucault or Jacques Derrida, but as Bartlett explains, the field is basically concerned with examining just about everything—history and politics, science and religion, music and dance—from the queer perspective.

The very word “queer,” Bartlett says, is about power and privilege, about defining who’s in and who’s out: “You could be black in some societies and be queer, or you could be white in Kenya and be queer, because you’re not in the norm.” (It should be noted that some may consider the term “queer” derogatory, but it has been reclaimed by the gay community and is often used by academics, says Bartlett, to describe whatever is deemed to fall outside the norm or majority.)

While it is anchored in considerations of sex and gender, queer studies is by no means relevant only to members of the LGBT community, nor is it always about them. Those who fall within the majority—including the archetypal “average straight white male”—can also get a lot out of it, such as a better understanding of how even the most normative gender roles (the breadwinner, the stoic) entail a variety of hidden costs.

Students majoring in a variety of fields can concentrate, or focus, in queer studies. They choose from a long list of electives that address the relationship between the normative and the transgressive, then apply what they have learned in a senior seminar in which they study a topic of their own choosing through a queer lens. It’s a model that encourages fresh thinking from both students and faculty members. The primary impetus behind queer studies—i.e., to question fundamental assumptions—is, as Bartlett puts it, “what we should be doing in the liberal arts, anyway.”

Alexander Gelfand is a writer in New York. His work has appeared in The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and The Economist.