Turning Toward Higher Ground

By Paul Pegher

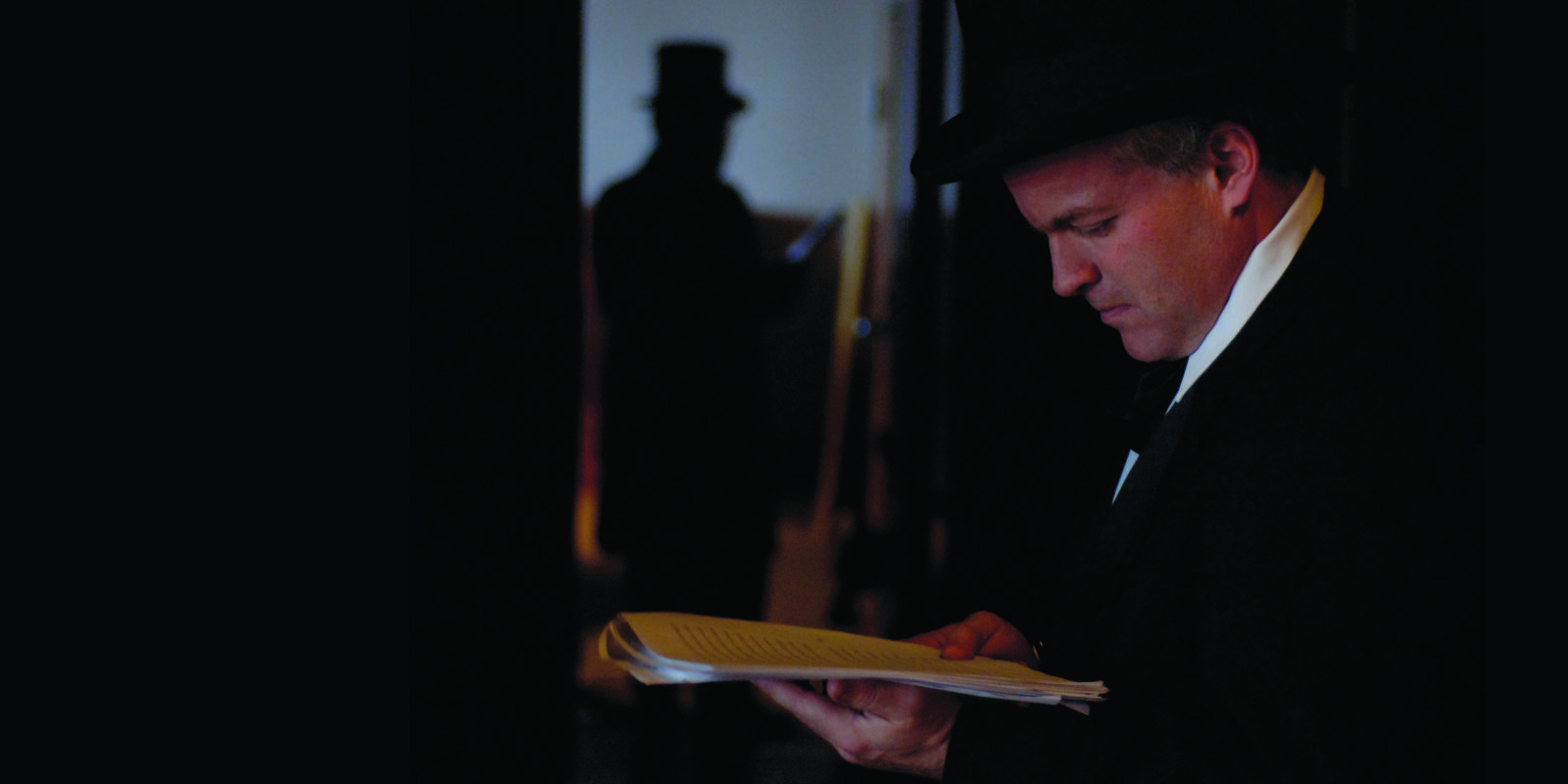

Throughout the 2006-07 Academic year, a number of events on campus—and even around the world—commemorated the 175th anniversary of the college’s founding. One such occasion was a performance by the Mighty Denison Art Players, a talented cast of faculty and staff formed abruptly (and solely) for a production on Dec. 13—the same date that the college’s first classes were held in 1831. Reading from a script by history buff and philosophy professor Tony Lisska, each actor portrayed a key figure from the college’s colorful history. To Greg Sharkey ’84 (pictured at left), fell the role of Jeremiah Hall, the college’s pivotal fourth president.

Having played a central role in the founding of Kalamazoo College, Hall knew a thing or two about education. Ironically, one of his first presidential acts in 1854 was to relocate the college from its countryside location—not away from Granville, however, but instead to the hilltop overlooking the village. Two years later, during the college’s 25th year, Hall secured a $10,000 donation from a farmer in neighboring Muskingum County. Several years prior, the trustees had proposed to rename the college after anyone who would give such an amount, and so the generous William Denison was granted an academic legacy. (Of course, as many Denisonians are aware, the college administration had to enter into “legal negotiations” with Denison’s family after his death in order to obtain the final $2,000.)

By 1863, the duties of office had taken their toll on Hall, and the tired visionary resigned, having established an endowment for the Denison University but perhaps still uncertain about its future, given the threats of a growing War Between the States. Had he but known that, 150 years after his time and 175 after his college’s founding, Denison’s status and future would be at their brightest.

Jeremiah Hall was the pastor of Granville Baptist Church in 1835, a time when the board of trustees of Granville College (as it was then called) were considering relocating the financially beleaguered school to another part of Ohio, where more resources and students would be available. In fact, they already had been offered $30,000 in support if the college would move to Lebanon, Ohio, near Cincinnati. But Hall urged the trustees not to forget the wisdom of founding president John Pratt, who insisted on the value of the college to Granville, and of Granville to the college. So strong were Hall’s feelings that he offered a deal: if residents of the surrounding region would raise $50,000 to demonstrate their support, then the trustees would agree to keep the the college in place. The trustees accepted his proposal, which was promptly followed by the resignation of then-president Silas Bailey, who had labored toward relocation. So the trustees looked to the confident and passionate Hall for leadership.

Ahead of the Curve

By Dale T. Knobel, University President

Higher education in America has had its fair share of attention in the popular press this year, filling up news and op-ed columns with questions about the value of standardized tests and magazine rankings of colleges and universities, about the promise of international collaboration in higher education, the reform of college athletics, and the challenges of creating college opportunities for urban youth. And it’s no accident that Denison University is at the center of national and international conversations about these topics. By virtue of our commitment to the principles of a liberal arts education and the nature of a residential undergraduate college, and by the testimony of strong (and getting stronger) application and retention rates, Denison is clearly viewed as a leading national liberal arts college. As Denison’s president, I spend a substantial portion of my time representing the college in some of the key discussions in contemporary higher education. The editors of Denison Magazine asked me to reflect on the college’s role in these issues and higher education in general.

Last year, Denison joined a small group of colleges in affording applicants, beginning in 2007-08, the choice of whether or not to submit an SAT or ACT score as part of their application package. The SAT and ACT are, of course, venerable mechanisms for winnowing applicants, but, in truth, they are far more useful to large universities with very large applicant pools and often overwhelmed admissions offices than they are to a historically selective college like Denison, which has the time, ability, and seasoned personnel to evaluate each student carefully on individual merits. Some of the flaws in standardized testing are well known and based on socio-economic and cultural factors—from the context of the testing material itself to the ability of some families or some school districts to afford repeated testing and/or test preparation curricula. Moreover, there has been no way for the exceptional student who does not shine on time-pressured multiple choice instruments to break through the standardized test barrier and get a fair hearing at college admissions time.

With more students than ever before seeking a Denison education (almost 5,200 applications for 585 places in the Class of 2011) and with a historic commitment to treat students as individuals rather than as numbers, Denison is in a position to offer students some application options. This year and in the years just ahead, most students, we expect, will continue to submit an SAT or ACT score as part of their application for admission. Others, however, will choose to submit alternate materials that prove they’re of Denison quality. Our standards for admission are high and trending higher, but we are among a select group of top national colleges saying that one size does not fit all in admissions. Denison was the first liberal arts college in Ohio to adopt this approach, and some of our peer institutions have endorsed our decision by following the same course.

As we reconsider how we evaluate aspiring Denisonians, the college also has taken a fresh approach to how it and other institutions are represented to prospective students and the general public. I refer, of course, to those rankings that were devised to sell magazines and that now face a growing chorus of public challenges by higher education leaders. I’m proud to share that on Denison’s behalf, I was one of the earliest signers of a public declaration by a non-profit reform group called the Education Conservancy pledging that Denison would not participate in misleading “reputational” surveys nor advertise our institution by touting our “ranking.” Why do it? Because the most well known ranking schemes are wrong—wrong in methodology and wrong-headed in conveying the notion that young people can make the best college match by drawing from a list.

Which colleges are in the best position to challenge these simplistic ranking schemes? Why, those—like Denison—that have no axe to grind because their “rank,” according to these publications, is consistently high. Accordingly, I will be among several dozen higher education leaders meeting at Yale University this fall to talk frankly about how we might better convey information of value to students and their families so that they can make good college choices. As president of the Great Lakes Colleges Association, I’ll have the opportunity to share some of the ideas that Denison and several of its regional sister institutions already have developed. We know that students and families want transparency from colleges, and so Denison is also a charter participant in the National Association of Independent Colleges’ new system to provide comparable information about several hundred colleges and universities, accessible at members.ucan-network.org.

Although American higher education receives its share of public criticism, as a “system” we remain the envy of the world. I was reminded of that last winter when I joined a handful of other American liberal arts college presidents at Oxford University to meet with a comparable group of presidents, rectors, and vice-chancellors of the growing number of American-style liberal arts institutions in Europe and the Middle East. Some of these institutions are venerable and well-known, like the American University of Cairo. Others are comparatively new but exhibiting strength, like John Cabot College in Italy, Franklin College in Switzerland, or the American University of Bulgaria. Each represents a departure from the traditions of British and Continental-style higher education that feature more narrowly-tailored preprofessional undergraduate education and a movement toward the liberal arts education familiar to all Denisonians and so well suited to preparing young people for a dynamic world and evolving careers.

Out of the meeting at Oxford grew a memorandum of agreement that, over time, may allow for the sharing of students, faculty, and staff across national and continental boundaries. It’s happening already. The American University of Cairo has just asked Denison Director of Athletics Larry Scheiderer to come and share advice on the creation of programs in physical education, athletics, and recreation. During my current term as GLCA president, I hope to advance the participation of all of our GLCA membership in this international initiative.

Denison is a proud member of NCAA Division III, the “nonscholarship” division of the nation’s largest inter-collegiate athletic association. In fact, we’re a founding member of the division, just as we were one of the three dozen founding members of the NCAA itself in 1906. Today, Denison is at the heart of conversations about the values of the division and of its future. A value dear to us at Denison is that student athletes are first and foremost students who owe their primary attention to academic achievement and who are owed by the college respect for their efforts to get the most out of all aspects of their education. But Division III today is by far the largest division of the NCAA, with members that have as few as a couple hundred students to as many as 30,000 and with a wide range of outlooks on the role of athletics in college life, and this has made the division difficult to manage.

In recent years, as president of the North Coast Athletic Conference, as a member of the Presidents’ Council which guides NCAA Division III, and as a participant in NCAA’s strategic planning and divisional structure task forces, I’ve had the opportunity to bring Denison’s perspective to bear upon the conversations taking place at the national level about how best to structure the NCAA to meet the needs of colleges like Denison and Kenyon, Dickinson and Gettysburg, Grinnell and Beloit (just to pick a few that share our outlook and concerns). The greatest temptation is to follow Division I universities into longer and longer playing seasons, year-round practices, and special treatment for athletes that separates them from other students. Denison is playing a visible and respected role in working for the preservation of some of the most important values in the Division III tradition.

Speaking of values and leadership, both have played central roles in the college’s involvement with the national “Posse” program. In fact, among the 28 colleges and universities participating in Posse, Denison is one of just six institutions working with two different Posse Centers (in our case, Chicago and Boston) and enrolling 70 Posse Scholars (80 next year when the fourth Boston Posse arrives). Posse is an extraordinary program that works with high school teachers and counselors from urban areas to identify young men and women who show promise as scholars and leaders, but would be unlikely to make a match with a leading college or university on their own. Once a posse of ten students is formed in the senior year of high school and admitted to a partner college, participants work together with skilled counselors through graduation to build teamwork skills, develop group esprit de corps, and grow in understanding of how to navigate the environment of a residential liberal arts college. After they arrive at Denison, Posse students melt into the student body but they know who one another are and they can count on each other to provide friendly support in the face of college challenges. I’m happy to report that at Denison Posse participants are faring very well, routinely graduating 90 to 100 percent of their members. Recruited to be leaders, students who come to the college through Posse can be found heading up student organizations, serving as residence hall staff, and participating in student governance. They take up the challenge of off-campus study, independent research, and career-formative internships. Several have been selected in national competitions to be named McNair Scholars and offered the opportunity to join summer research teams at major research universities. Posse is a big commitment for Denison. Typically, participants qualify for full tuition financial aid, and the college helps support the Posse centers in Boston and Chicago. And in return, Posse has broadened Denison’s reach and impact and brought to us remarkable women and men.

Denison’s leadership in Posse has not gone unnoticed. This fall, I’ll attend a gathering of college and university presidents in New York sponsored by the investment firm of Goldman Sachs to discuss how we can build upon Posse’s strengths. Employers in all sectors have taken an interest in this program and its graduates because they, too, want to identify new pools of educated, talented young people.

In mid-October, Denison will host a symposium in honor of Bill Bowen ’55, former president of Princeton University and of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and in gratitude for the exceptional gift to Denison made by the Mellon Foundation to recognize Bill and Mary Ellen Bowen ’55. Fittingly, the topic of the symposium is “Equity and Excellence in Liberal Arts Education,” a key theme in Dr. Bowen’s own scholarship, and will feature presentations by Dr. Michael McPherson, an economist and president of the Spencer Foundation, Dr. Debra Bial, founder of the Posse Foundation, and Dr. Sylvia Hurtado, executive director of UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute. I’m pleased to have the opportunity to moderate such an important conversation by these important figures in contemporary higher education leadership.

Several years ago, we asked an accomplished Mid-western folk artist to carve a unique academic mace for Denison. Academic maces are an ancient tradition in higher education and originally represented the stature of the faculty as a self-governing corporation. Over time, they came to represent the autonomy of colleges and universities themselves. Denison’s mace, carried in academic processions by the chairperson of the faculty, portrays in walnut and silver the theme “rooted at Denison, branches to the world,” representing Denison’s sons and daughters, who have made a difference in the world as students and graduates. But it also captures the essence of our historic college, operating for 176 years in the arena of national and international higher education—and truly making a difference.

Chasing the Dream

By Barbara Stambaugh

Forget, for a moment, that Elaine Binkley ’07 can run like the wind; tune out her NCAC honors and championships; put aside even that last year she was named the ESPN The Magazine’s Academic All American of the Year for the college division in cross country and track and field. Focus, instead, on Binkley, the scholar. As a biology major, she conducted research, co-authored papers and presented her work at national gatherings of scientists. She was a President’s Medalist, Phi Beta Kappa, and co-valedictorian with a perfect 4.0. Perhaps most impressive, Binkley was a finalist for the Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford University.

And almost impressive as that distinction is the amount of work required to apply for a Rhodes. “The process is intense,” says Kent Maynard, professor of anthropology and director of the Honors Program, which helps students apply for premier awards like Marshall and Fulbright scholarships and National Science Foundation fellowships. “All told, she may have invested hundreds of hours.”

Binkley started her Rhodes chase in the summer after her junior year. She had conversations with faculty and Honors Program staff members to focus her goals. She drafted and redrafted her essay and proposal, which then underwent intense committee review on campus. She went through mock interviews, defended her proposal and even prepped for the social aspects of the application process at a formal reception.

But it’s not enough to be (very) smart and (very, very) accomplished to seek a Rhodes; the qualifications are highly specific. Applicants have to be a good fit in several categories, including having an academic interest that matches programs offered at Oxford. And there’s a controversial element known as “vigor,” which was held to mean “men only” until an act of Parliament in the 1980s changed the program to include women. Now the Rhodes definition of “vigor” is more inclusive (and more difficult to pin down), and Binkley’s athletic prowess probably didn’t hurt her application, Maynard says.

But the crux of her application was Binkley’s desire to practice medicine research and someday develop public health programs that utilize sports, such as running, to help people prevent and manage medical conditions, like type-II diabetes.

“Ohio unfortunately has the third highest mortality rate due to diabetes in the Unites States,” Binkley wrote in her Rhodes application, stating her plan to earn a master’s from Oxford’s program in science and medicine of athletic performance and then head back to Ohio State for medical school.

And when she just missed the Rhodes, Binkley headed straight to Columbus for med school with her dreams intact. “To be named a finalist is extraordinarily prestigious,” Maynard says, given that so few colleges have students in the running for this award.

Binkley says the experience was good. “[It] helped me to define more clearly the reasons why I wanted to go to medical school,” she says. “I was extremely grateful to the people in the Honors Program and to the faculty … It showed what a great place Denison is to have faculty who are willing to take so much of their time to help with a process like that.”

Master Stroke

By Barbara Stambaugh

Gregg Parini’s office in the Mitchell Recreation and Athletics Center teems with stuff. Splashed across the walls and surfaces is the impressive and good-natured evidence that he is a champion swimming coach, athletics educator, über-dad, and athlete—though not necessarily in that order. Kid art prevails. Parini and wife Alice have six sons, ages 2-20. From the looks of one wall’s barmy patchwork of drawings, most of the six have done crayon duty. On his desk: heavy-metal action figures. “Metallica,” Parini says, laughing. “Energy. Intensity.” Near the door, a poster-sized Butch and Sundance make a break for it.

Every other square inch, it seems, holds photos of swimmers, flocks of them—all with wet hair and big grins, many of them posed in groups with their arms thrown around each other’s shoulders. Parini points at them and tells their stories, recites their names and achievements. One went on be a Paralympian champion, and one swam for the Lithuanian Olympic team in 2004. One is a layout artist for The Simpsons. One was killed in a skydiving accident, five years after she graduated. “Deb Luhmann [’96],” Parini says. He picks up her picture and puts it down, turning it toward the light. “She was important to all of us. The number of her teammates who came to her funeral in Chicago just blew me away.” The coach who was light-hearted a moment ago turns quiet and serious. “What matters here are the people,” he says.

He acknowledges that the wins are important, and the awards matter to him. In April, for example, he received the Charles A. Brickman Excellence in Teaching Award, Denison’s highest faculty honor, given each year to a professor in recognition of a sustained exemplary teaching record. It’s preceded by a list of athletics accomplishments as long as his arms (and he has long arms), including 40 straight top 10 finishes at NCAA Division III Championships, 200 All-American scholar-athletes, and 40 consecutive Team All-Academic honors.

“There are some swims that will stay with me forever,” Parini says. “The 2001 National Championship was huge. But swimming is as much lifestyle as sport. The prevailing paradigm is two practices a day. Travel. Meals together. They build camaraderie.”

Parini says that what distinguishes Denison swimming is that these students invest in something bigger than themselves. Swimming is an internal challenge—it’s just you and the pool—but any suggestion that his is not a team sport doesn’t wash with Parini. “I watch strangers turn into teammates, then friends, best friends, maids of honor, godmothers to each other’s kids,” Parini says. “It’s gratifying to me.”

It’s this up-close and personal style of practicing his craft that has helped to earn Parini the respect of his peers. “He follows his students’ progress, both inside and outside the classroom,” says Keith Boone, associate provost. “He attends to the whole person—body, mind, and spirit. His ability to convey mental discipline while building a scaffold of support for his students has led to his widely recognized successes at Denison.”

Parini admits that success at this level takes an internal fire that burns hot—not only for his students, but for himself, too. He’s been accused of being an intense guy. His smile at that notion says there’s no denying it. “I’m still intense,” he says, “but with maturity you get better at standing back and taking stock. I used to live and die with the swims. You can become blinded by that kind of passion. In the moment, you can miss key details.”

And because Parini is tall and athletic, he worried that his physical stature combined with such an intense personality could be intimidating. “Besides, I’m 47 now,” he says. “You have to pace yourself. What I used to accomplish with intensity, I now accomplish with efficiency and patience.”

With Gratitude & Respect by

Fleur w. Metzger

Illustrations by Lara Tomlin

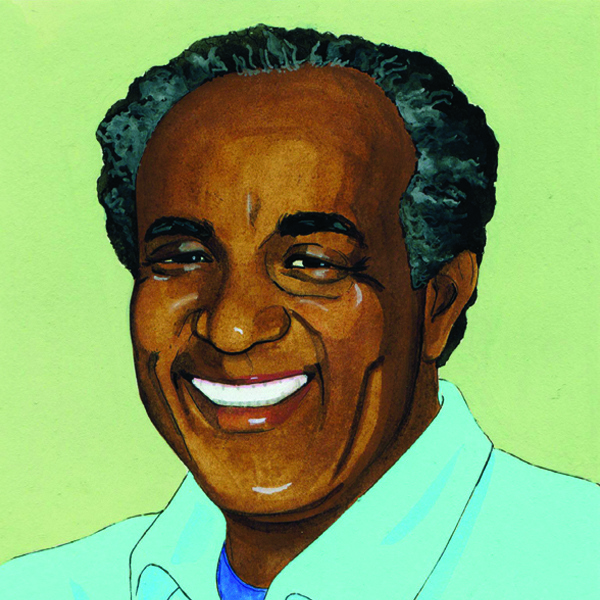

Desmond Hamlet

Lorena Woodrow Burke Chair Of English & Professor Emeritus Of English

For 23 years the deep, resonant voice of Professor of English Desmond Hamlet filled classrooms and minds with teachings on literature from around the world, the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., and even once as the voice of God, whom Hamlet played in the 2002 morality play Everyman. Sadly, that unmistakable voice fell silent on September 14, as Hamlet died in his home, surrounded by family.

Hamlet came to Denison as an expert on 17th-century-British literature and, particularly, on the rebellious poet of the time, John Milton, about whom Hamlet wrote the 1976 book One Greater Man: Justice and Damnation in Paradise Lost. His scholarship later shifted to African, African-American, Post-Colonial literature, and he was counted among the world’s experts on the Nobel Prize winning Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka and on Wilson Harris, the prolific Caribbean writer.

He also became deeply involved in the Black Studies Program at Denison and served as an adviser for the Black Student Union for 10 years. During that occasionally turbulent period, during which he continued to push for greater diversity at Denison, his wisdom and calming presence enabled many factions and individuals on campus to express themselves and talk to one another. In recognition for his unfaltering influence, Hamlet was the first faculty recipient of Denison’s Martin Luther King Jr. Leadership Award in 2005.

A native of Georgetown, Guyana, Hamlet was a summa cum laude graduate of the Inter-American University in Puerto Rico. He earned a bachelor of divinity degree with distinction in English from Waterloo Lutheran University, Waterloo, Ontario, and an M.A. and Ph.D. in English from the University of Illinois. Before coming to Denison, Hamlet was an associate professor of English at the State University of New York in Buffalo. He was also a senior lecturer at the University of Ife in Nigeria, West Africa, where he lived from 1976 to 1983.

His natural grace and authority served him well as English Department chair from 1996 to 1999, working on the expansion of the Global Studies Program, in the Academic Affairs Council, and on the Black Studies and Latin American Studies Committees. In 1988, Crossed Keys Honorary Society named him the Faculty Member of the Year. In 2001 Hamlet was named Lorena Woodrow Burke Chair of English, a title he held into retirement. He is survived by his wife of 47 years, Barbara, and their daughters, Sharon and Lawrence.

Editor’s note: Desmond Hamlet passed away as this publication was in the final stages of production. We will pay proper tribute to Desmond and his contributions to this world in the next issue.

With Gratitude & Respect by

Fleur w. Metzger

Illustrations by Lara Tomlin

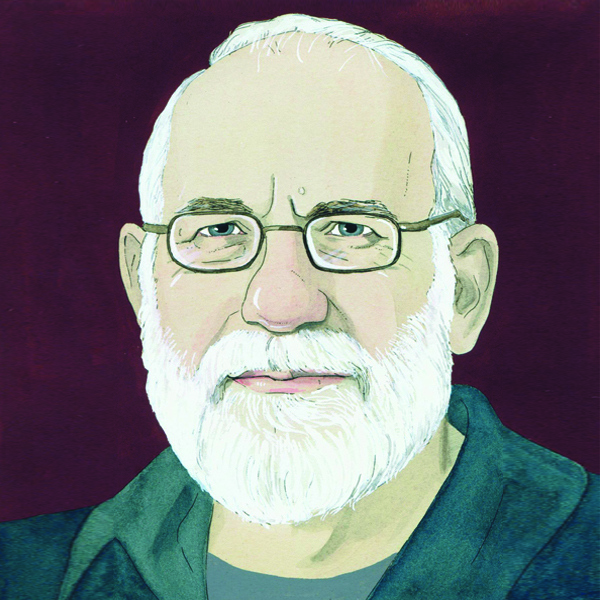

John David Kessler

Associate Professor Emeritus Of Modern Languages

John Kessler is an man who excels in Languages, German literature, mathematics, music, local history, and athletics. He brought this combination of talents to Denison’s Modern Languages Department in 1969, when he was hired as an assistant professor of German.

A native of Wayne, Neb., Kessler grew up playing the violin and trombone and was part of a chamber group during his two years at Wayne State College. He transferred to Ohio Wesleyan University where, as a mathematics major, he became interested in German while fulfilling the foreign language requirement.

After earning a bachelor of arts from Ohio Wesleyan with honors in mathematics in 1963, he won a fellowship to the University of Texas at Austin where he earned both his M.A. and Ph.D. in German literature and linguistics. During that period, he also studied at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, Germany, researching Thomas Mann’s relationship to the theater. After being named associate professor at Denison in 1975, he returned to Munich to do further research during a sabbatical.

Students in his classes addressed him as “Herr Kessler” and many have stayed in touch with him years after their graduation. An important part of Kessler’s life outside the classroom was his love for athletics, whether it was racquetball, squash, handball, tennis or running, and he frequently competed with colleagues in Livingston Gymnasium. His sonorous bass voice was a significant part of Denison’s Concert Choir for many years. In 1974, he translated the text of “The First Walpurgis Night” by Felix Mendelssohn for a performance by the 110-voice choir that was accompanied by a 45-piece orchestra and four visiting soloists.

During a walk through the Old Colony Burying Grounds, Kessler discovered the tombstone of his ancestor, Samuel Thrall, who was born in 1760 and was a member of the first party to leave Granville, Mass., and Granby, Conn., to settle in Granville Ohio. Kessler has served as a docent for the Granville Historical Society for many years.

Since 1980, when Kessler suffered a nearly fatal stroke, he has resolutely overcome many of his physical disabilities, continuing to tutor students in German and conduct private lessons. Among his current students are two former colleagues, professors emeritus Bill Hoffman and Dan Fletcher. Kessler and his wife, Eloise, who now live at Kendal at Granville, are the parents of David and Elizabeth Claire.

Bahram Mehdi Tavakolian

Professor Emeritus Of Sociology/Anthropology

Bahram Tavakolian has thrived at Denison for 28 years because its liberal arts mission engages both students and professors in active learning, his own personal objective in academia. During those years he has taught 45 different courses, with one or two new ones each year, on subjects as wide-ranging as gender and development, baseball and the American dream, social deviance, cross-cultural perspectives, and the Middle East.

Shortly after arriving from Mount Holyoke College, Tavakolian helped to merge the Sociology and Anthropology departments, creating a balance between the two disciplines, and achieving a common curriculum and sense of mission. Tavakolian believes that students in this major are well prepared for lives after Denison and is particularly proud that each of them is required to complete a senior research paper. A true disciple of interdisciplinary learning, he also has been active in Global Studies and Women’s Studies, winning the latter’s Feminist Teaching Award in 1997. He served his final year as the Anne Powell Riley Director of Environmental Studies.

Tavakolian’s interests include cultural theory, nomadic pastoralism, women in third world societies, economic and cultural imperialism, British India and the 19th-century Afghan state, and particularly the countries of Iran, Afghanistan, and Turkey. His early classes on the Middle East were more ethnographic, but in the last decade his teaching has been focused on the area’s politics and economics so that students understand the interdependence between the West and the Middle East, and the cultural changes that have occurred. His expertise in that area has enabled him to educate students, retirement groups and church members to have a better understanding of Islam and Muslim, the differences between Sunni and Shia, and the history and politics of the region.

A native of Iran, Tavakolian earned an A.B., M.A. and Ph.D. in anthropology with honors from the University of California, Los Angeles. In the fall, he will join the Anthropology Department of Willamette University in Salem, Ore. The following year, he hopes to be at Middle Eastern Technical University in Ankara, Turkey. He and his wife, Susan, are looking forward to their new life in the Pacific Northwest and being near their son Jason, his wife, and their two children.

Strength in Numbers

By Paul Pegher

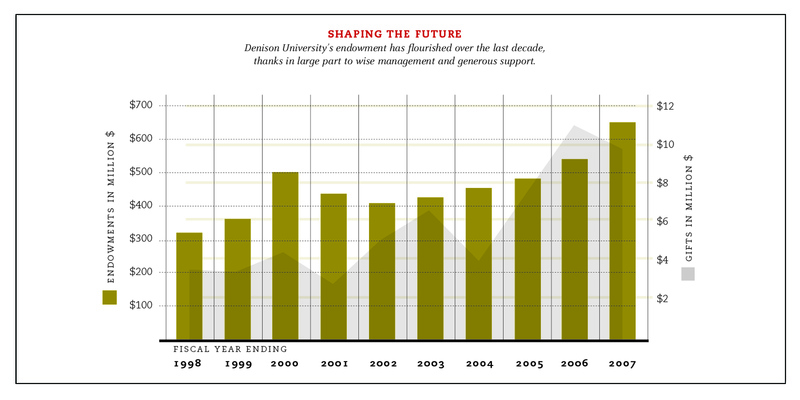

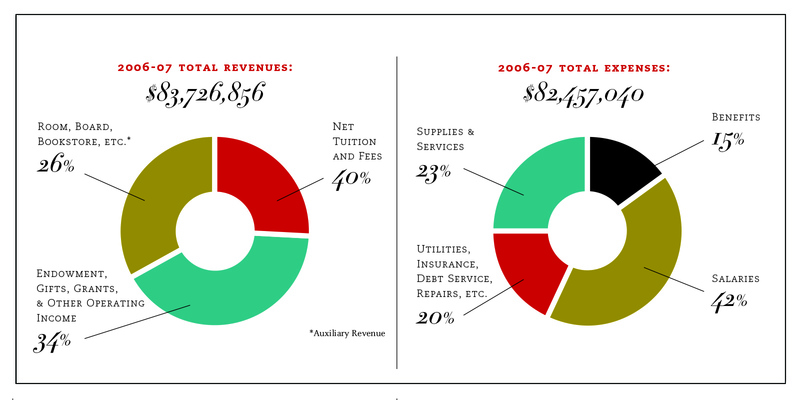

Denison University’s Healthy Endowment continued its five-year climb in fiscal 2006, taking its biggest leap in as many years and reaching a new high of $645 million. Of course, the milestone would not have been reached without the generous support of so many loyal members of the Denison family. Credit also goes to the board of trustees and the college administration, whose sound fiscal policies and savvy decisions have protected and cultivated Denison’s financial future. At the heart of this strategy is spending no more than five percent of a 12-quarter trailing average of the endowment, regardless of whether the fund is up or down. “This smooth flow of withdrawals has allowed the endowment to grow and has made sure that our income stream for operations from the endowment has been quite level, growing in a measured way over time,” explained President Dale Knobel.

In fiscal 2007, the endowment generated a net investment return of 23.2 percent, versus 13.3 in fiscal 2006. The market value increased by $112 million over the year, during which the endowment contributed $20 million to college operations, or just about $10,000 per student (the second-highest amount in the Great Lakes Colleges Association).

But to place the issue in broader perspective, an annual survey of the National Association of College and University Business Officers shows that among the 772 reporting public and private institutions, Denison ranked 117th in terms of total endowment size, and 69th out of 517 private colleges according to endowment per student. And in terms of average annualized return over 10 years, Denison ranks 37th among the 477 colleges and universities that participated in the survey from 1996 to 2006.

Good Questions

News of a record-high endowment may, quite naturally, raise some questions among the Denison family, particularly over whether their financial support of the college is really necessary. It certainly did for us, the editors of this magazine, so we took those questions to our fundraising colleagues. Here are some of the answers we received:

Q: If the endowment is so strong, then why is the Denison Annual Fund necessary?

A: Even though endowment returns contribute $20 million to the college’s annual operations, much of it is for very specific purposes—like named professorships and scholarships—as directed by the donors donors who established those endowments. As critical as they are, endowment funds are quite inflexible, and unable to take on new and necessary initiatives. The Annual Fund also covers a significant number of scholarships, as well as faculty salaries and resources, operational costs, and even some capital improvements that require immediate attention—costs that may vary from year to year but otherwise are necessary for the college to function. In essence, gifts to the Annual Fund are direct investments in students and faculty, providing students with the resources to learn and live here and professors with the resources that enable them to function at the top of their fields while maintaining close interaction with their students. In other words, the Annual Fund provides the fuel that enhances relationships, and that ultimately changes lives.

Q: So even if the Annual Fund is important, does my small gift really matter?

A: Yes! Broad participation and collective impact is critical. Small gifts ($100 to $500) in last year’s Annual Fund totaled more than $1 million. To receive that amount in returns from the endowment would require an additional $20 million in that fund. Needless to say, it’s much harder to come by $20 million than it is all those small but ever-so-valuable gifts. And leadership gifts over $1,000, of course, make a huge difference in what we are able to deliver to our students.

Q: Why should I support Denison when there are so many other causes that need my help?

A: All around the world today, Denisonians are playing key roles in the central issues of our time. They are working to fight hunger, to curb the proliferation of nuclear weapons, to mediate between nations, to find cures for diseases, to launch important business ventures, and to teach the next generation of problem solvers. Meanwhile, back on campus, members of that next generation are learning to address the opportunities and challenges of tomorrow, and in some cases they’re already making a difference through innovative independent research, passionate social activism, and tireless volunteer work. Whether they make their impact today or in years to come, Denisonians’ contributions to this world are possible largely because of contributions to the college by Denisonians who preceded them and other friends of the college.