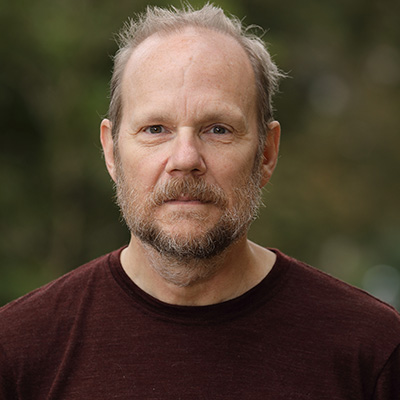

Visiting assistant professor Brad Lepper has a catalog of stories about the decades-long quest to get the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

But one story lives long in his memory — and demonstrates the challenge Lepper and his fellow Earthworks advocates faced.

Before convincing the World Heritage Committee of the cultural significance of eight Ohio earthen enclosures built by Indigenous peoples around 2,000 years ago, they needed to educate local residents on the architectural and geometric wonders staring them in the face.

Lepper, who teaches anthropology at Denison, was working at the Newark Earthworks Visitors Center in the ’90s when his wife stopped at a car dealership across the street from a section of the Great Circle Earthworks. She explained to the salesman that her husband worked at “the mounds,” a revelation that was met with a blank stare.

“His office window was facing the Great Circle,” said Lepper, who’s also the senior archeologist for the Ohio History Connection’s World Heritage Program. “But he didn’t see an ancient monument created by people. He saw a grassy slope with trees on it. We knew we had our work cut out for us.”

Joining the ranks of Stonehenge

Thanks to the indefatigable efforts of Lepper and a legion of collaborators, the World Heritage Committee inscribed the Ohio entry on Sept. 19, 2023. Two of the eight mounds, Great Circle Earthworks and Octagon Earthworks, are located just minutes from campus in Licking County. The remaining six are in Warren and Ross counties.

The collective enclosures mark Ohio’s first World Heritage site, and just the 25th overall in the United States. It joins a list of about 1,000 worldwide entries that include Stonehenge, the Great Wall of China and the Pyramids of Giza.

Erik Klemetti, chair of Earth and Environmental Sciences, has led field trips to the mounds and considers them an invaluable resource for research. He’s hoping the World Heritage designation encourages more students to visit them.

“It’s a miracle that so much of the Earthworks survived after the region was settled by white settlers,” Klemetti said. “Any additional protection and acknowledgment of their special place in world history is justified and warranted.”

Denison scholars have brought attention to the mounds since 1836 when the school was known as the Granville Literary and Theological Institution. Lepper calls the research done at the Octagon — its findings recorded by the school’s Calliopean Society and preserved in the University Archives — “the birth certificate of scientific archeology in Ohio.”

“At that time, most archeologists were just digging up cool stuff to put into cabinets of curiosity or museums,” Lepper said. “This was pioneering research that tested a hypothesis. I asked the library to scan the original handwritten documents so that we could showcase Denison’s role in all of this.”

Lepper helped found the “Friends of the Mounds” group, the first of many coalitions to be formed in pursuit of World Heritage recognition. Other members included Michael Mickelson, emeritus professor of physics and astronomy; Dick Shiels, a Granville resident and Ohio State University-Newark professor; and Jeff Gill, a Newark Earthworks Center volunteer.

Over the years, they created a vast network of allies in numerous agencies and at all levels of government. Political, bureaucratic and legal hurdles have been many, including a spat with Moundbuilders Country Club which leased its property in 1910 and developed a golf course on the site of the Octagon.

Gill recalls a conversation with an official from the U.S. Department of the Interior as the group prepared its initial World Heritage application in 2006.

“She told us it will take at least 15 years and asked, ‘Do you think you can stay the course?’’’ he said.

Tireless advocates

Gill knows of at least four longtime Earthworks supporters who died before seeing their dream of World Heritage status realized. It’s a process so lengthy, Gill observed, that it cannot be dependent on one person or a single institution.

Lepper said it was vital to gain the support and participation of descendants of the Indigenous people who created the Ohio earthworks. Chief Glenna Wallace, of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, joined the coalition around 2006 and has been a tireless advocate for inscription.

“I felt it was a fulfillment of an obligation to the ancient Indigenous people to see their amazing achievements inscribed along with these other wonders of the world,” Lepper said.

His research contributed heavily to a 332-page dossier submitted to the World Heritage Committee. It included details of how the Newark Earthworks track an 18.6 year lunar cycle where the central axis of the Octagon aligns with the northernmost rising of the moon.

In the 1970s, two Earlham College professors concluded the walls of the Octagon “define the most accurate astronomical alignments known in the prehistoric world.” In 2005, Lepper, Mickelson, Gill, and Shiels stood on the Octagon’s observatory mound and confirmed the professors’ hypothesis. The four men are believed to be the first in nearly 2,000 years to purposely observe the phenomenon.

Lepper traveled with an Earthworks contingent to Saudi Arabia, site of the 2023 World Heritage announcement, and was thrilled to hear glowing feedback about their work. “We were told it was one of the best nomination documents they had received,” Lepper said.

The Earthworks sites have seen an uptick in visitors since the World Heritage announcement, a gratifying trend for those who have spent nearly three decades in search of the UNESCO designation.

“With the world coming to these sites,” Lepper said, “maybe we can get people to appreciate what they have in their own backyard.”