When classes resumed in October 1918, Denison was facing two powerful crises: an impending pandemic, and also the more visible and immediate disruption of World War I.

The virus still hadn’t reached Granville at the start of term, but it was expected, as news from the east coast reached Ohio. Commonly called the “Spanish Influenza,” it’s now understood to have been a variation of the H1N1 virus similar to the bird flu we know today. A major outbreak was first reported in Spain, where the press was uncensored due to that country’s neutrality in the ongoing war, so Spain’s news coverage of the epidemic earned it the unfortunate name.

While the reality of the flu was genuine but still invisible, the senior class of 1918—96 men and women—had been nearly halved, as most of the men weren’t returning to Granville but had boarded ships to fight in Europe. They took with them the academic, cultural, and athletic leadership expected of the rising senior class, and it was a strongly felt loss on campus.

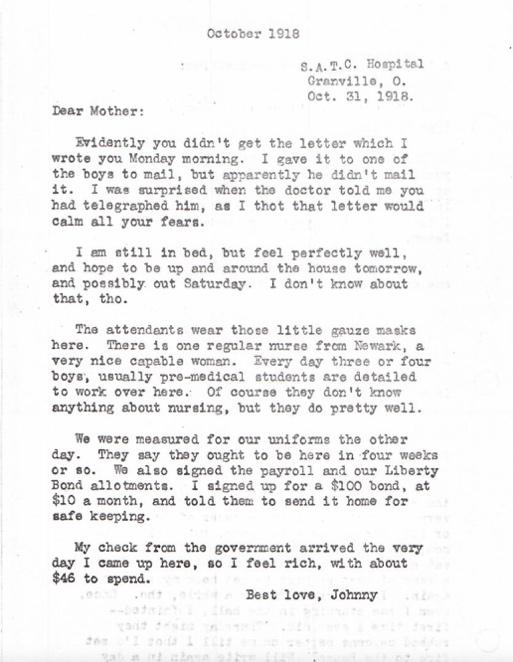

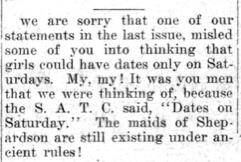

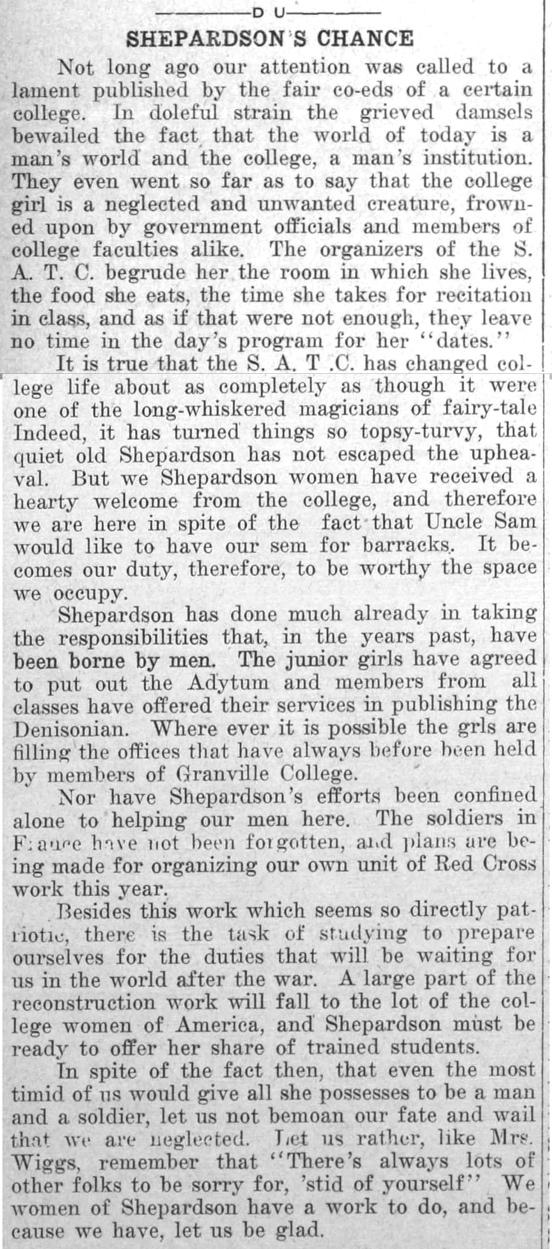

The U.S. War Department was introducing the Denison Unit of the Student Army Training Corps (the S.A.T.C.), a program that made use of existing university facilities to train young men for war, specifically for officer positions. There was a great demand in that patriotic moment, and young men wanting the leg-up in rank and opportunity (as well as to earn pay and avoid conscription) flocked to Denison to fill the promised 400 positions. In return, the War Department took control of the men’s curriculum and the campus’s few facilities to create barracks, a mess hall, study halls, and spaces for regular drills.

On October 11, 1918, the first issue of the Denisonian describes the early autumn scene of Denison men taking the Oath of Allegiance: “virtually the entire male registration of an American college assembled to pledge their allegiance to the flag and turn their college work into the channel of enlisted preparation for service on the field of battle.”

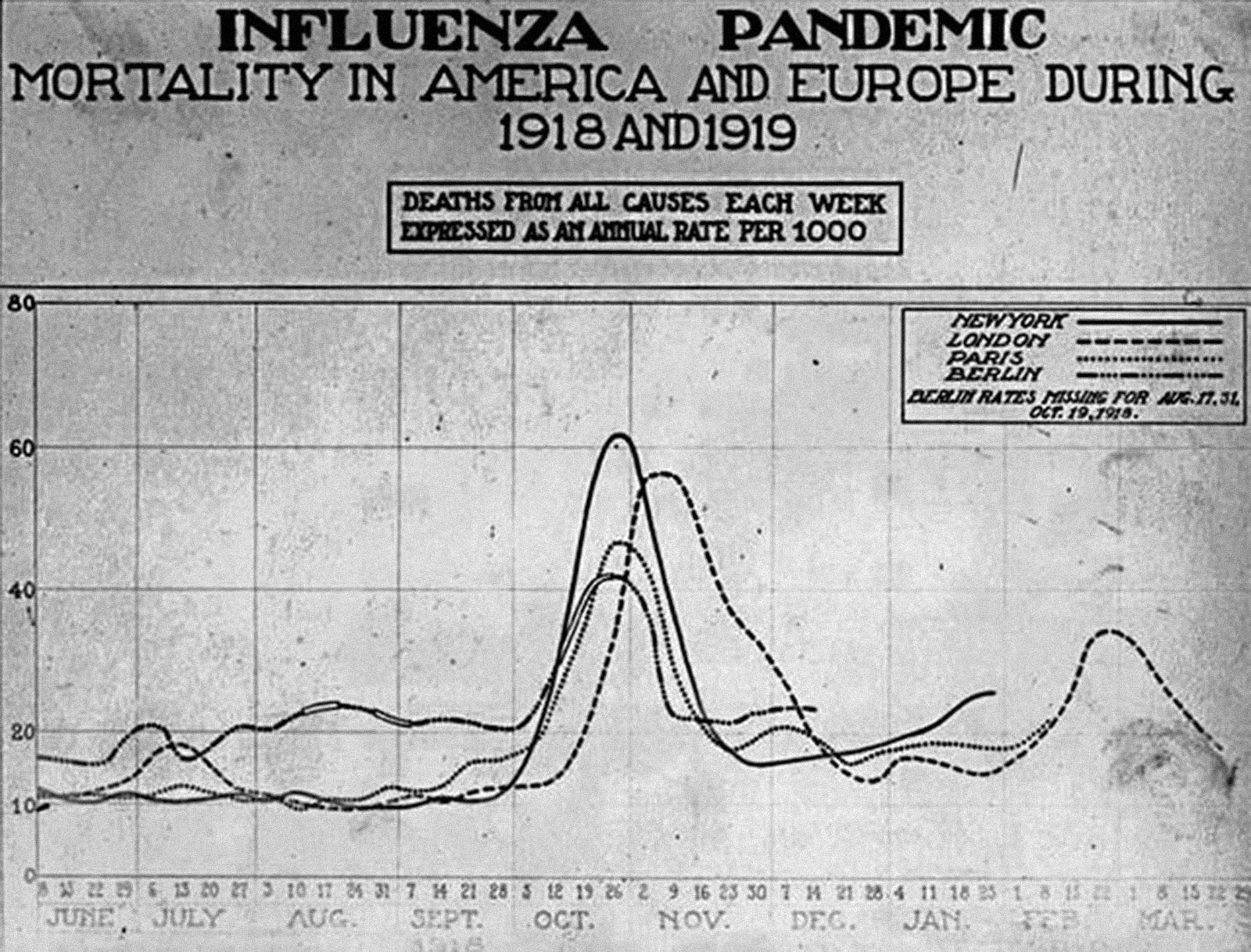

The second, deadlier wave hit in September on both sides of the Atlantic, and after a large Philadelphia “Liberty Loan” parade that month, the city was brought to its knees with new cases. Nearly 14,000 Philadelphians died within six weeks. Workers from the Bureau of Highways dug mass graves using steam shovels. To quell panic, residents were told to “Live a clean life. Do not even discuss influenza … Worry is useless. Talk of cheerful things instead of the disease.”

News of the Philadelphia outbreak and death toll likely reached Granville by October, but there was little to report from here at the start of the month beyond vigilance.

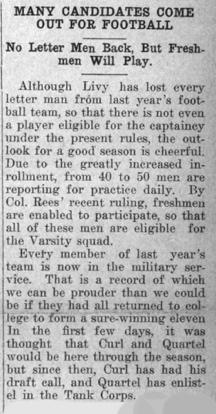

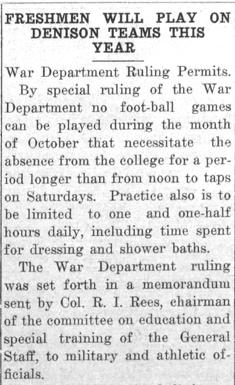

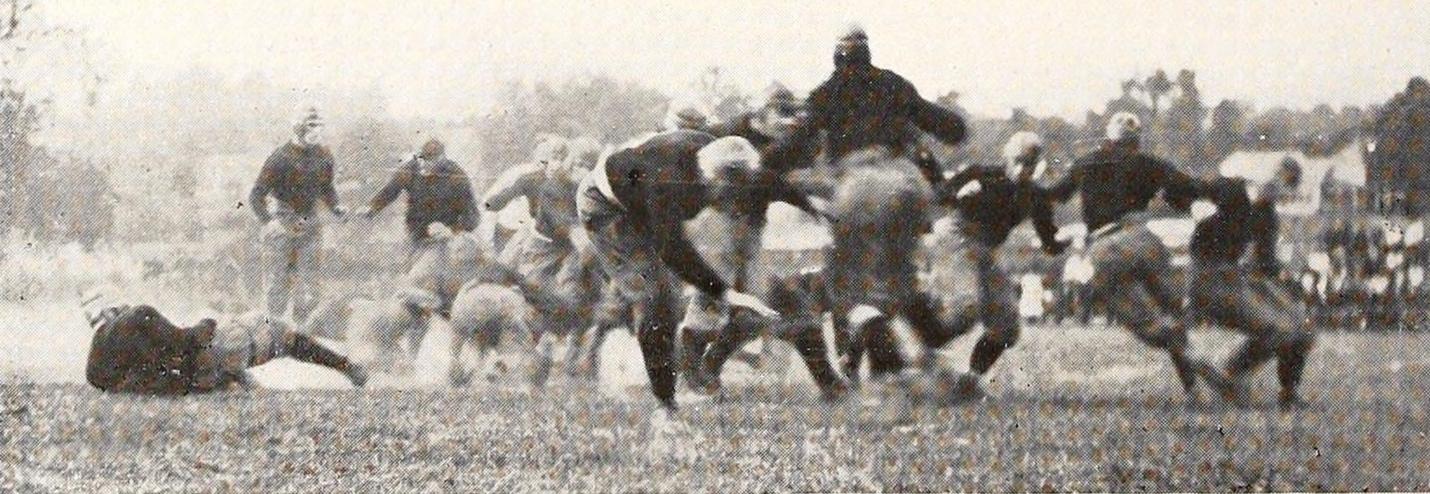

In spite of the flu and the war, early October meant that football season was on the minds of many, and there was a lot of talk about how to build a team when every senior varsity star had gone to war. Freshmen had always been barred from varsity teams, but Coach Livingston opened eligibility to the eager fellows, with special permission from the War Department.

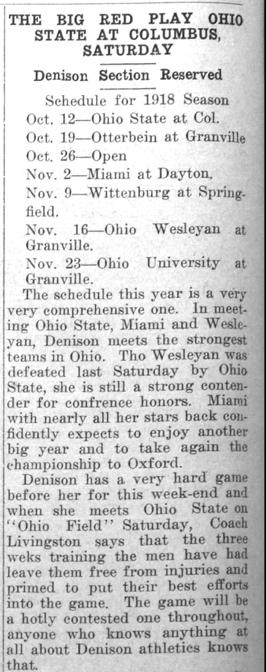

Denison’s opening game was with Ohio State at “Ohio Field” in Columbus, and the gung-ho scrappy optimism of Denison comes across in the anticipation, and just as much in reporting the loss.

A different point of view just ahead of that game was published in Ohio State’s paper, The Lantern which reported a mistaken view of Denison’s circumstances at a time when there were no cases of the influenza on Denison’s campus. Denison’s football “stars” were actually fighting in Europe. But Ohio State itself was struggling with a flu outbreak, and classes were canceled for a week, something that never happened at Denison.

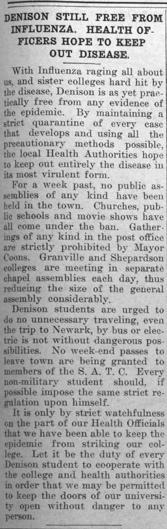

By the next weekly issue of the Denisonian, October 18th, the virus had arrived in town and on The Hill, with 132 cases in and around Granville, two of which had developed into pneumonia. No deaths were reported. At Denison, the women in Shepardson College had no cases yet, only a few students with “grippe,” or regular flu symptoms.

The S.A.T.C. men had “about a dozen mild casualties” who were being quarantined in the Phi Delta Theta house. This house, once owned by the Colwell family, was used for many years as administrative staff offices, where it stood in front of Gilpatrick House on chapel walk until 2003. The original Bandersnatch was in an extension built onto the back end of Colwell House. But in 1918, it was the men’s hospital for the pandemic.

In 1918, Granville and Denison both had much smaller populations, and were more insulated from the outside world, a strong advantage in a pandemic. The total number of regular Denison students that year was 411, plus 330 additional S.A.T.C. men. Train and interurban allowed people to come and go from Granville, but the streets were still unpaved, automobiles were relatively scarce, and people were following directions to stay at home.

Compared with the cumulative total of 132 Granville flu cases, nearby Newark reported ‘Nine Deaths and 184 New Cases of ‘Flu’” in just one 24-hour period, October 14. That same day, the military base at Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, south of Columbus, added one more man to its count of 938 deaths so far from the flu.

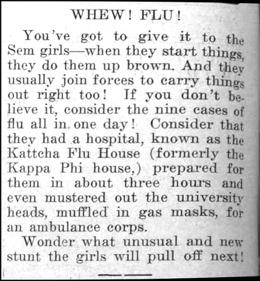

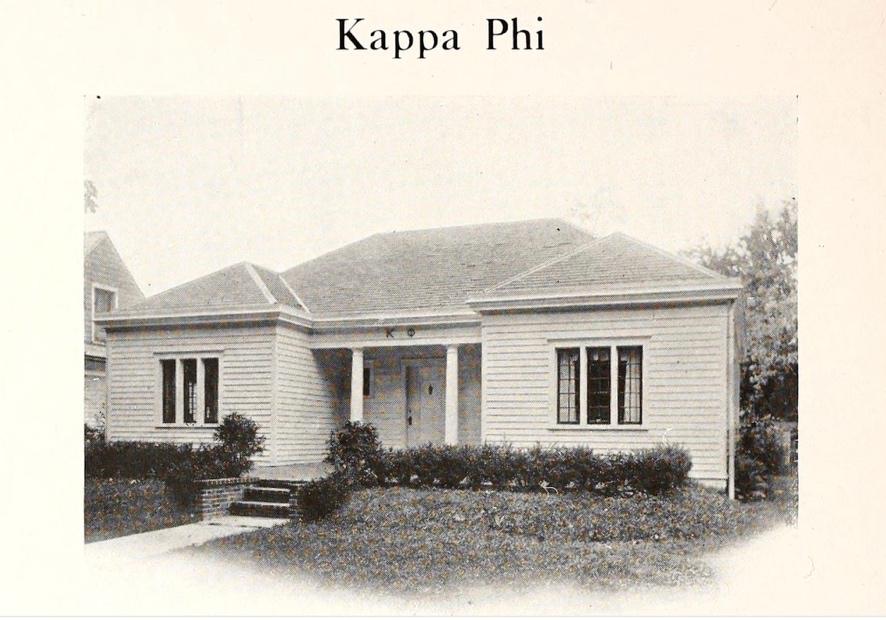

While Denison’s cases appeared to have started with the S.A.T.C. men, it wasn’t long before the women of Shepardson joined their numbers, and a second infirmary was created for them in the nearby Kappa Phi sorority house on Cherry Street.

Granville’s newspaper and local printer, The Granville Times, suspended publication indefinitely in October due to war shortages, but Denison’s administration decided to support the Denisonian as a valued part of university life and found special funding for it. A page of the college paper was reserved for local Granville news, including social notes and observations from Mrs. Burton Case.

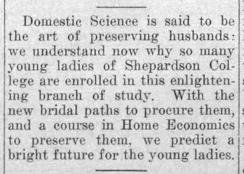

With men distracted by war, the Denisonian was largely handed over to the women of Shepardson for the duration, and their voices brought an unmistakable shift of tone and topic to the weekly. Case’s was a popular candy and soda joint with students, especially the women of Shepardson who could easily walk to the Opera House from their lower campus living quarters.

The pandemic didn’t appear to be at the very top of their list of serious concerns. This was a time of transition from separate men’s and women’s institutions, which hadn’t quite fully merged by 1918. The women, who lived on the lower campus, referred to themselves as Shepardson, or “The Sem” after the old Seminary for women, and sometimes wittily called themselves “Semites.” The men on The Hill were generally called “Granville College,” the name for Denison prior to the mid-1850s. “Denison” was used when men and women were referenced in aggregate.

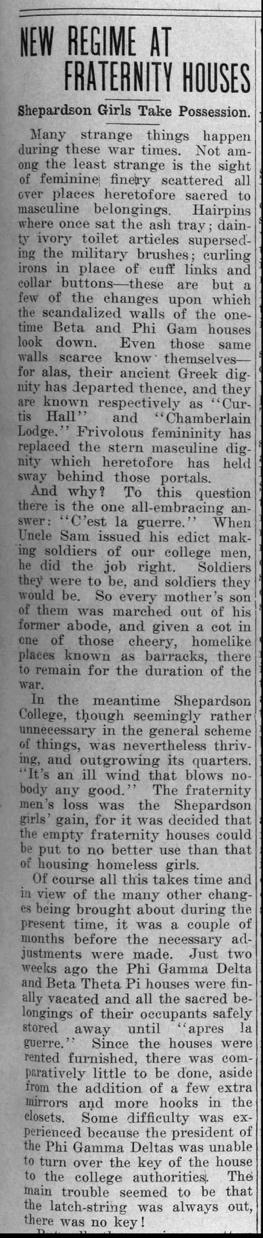

Housing for the men was in town, where fraternities were scattered in houses through the village. The S.A.T.C. required all the men move into the campus academic buildings—Marsh, Talbot, and Barney—to set up their cots barracks-style. Shepardson was short on space for its women, so the overflow was moved into the emptied fraternity houses.

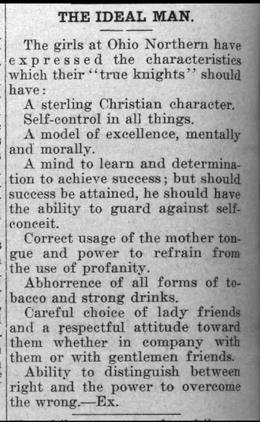

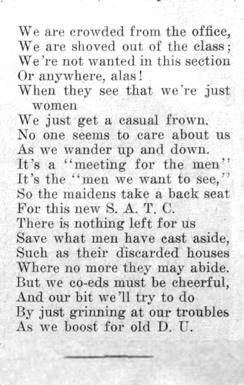

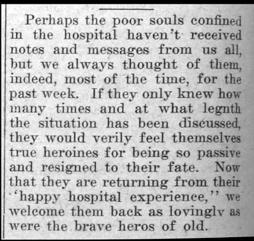

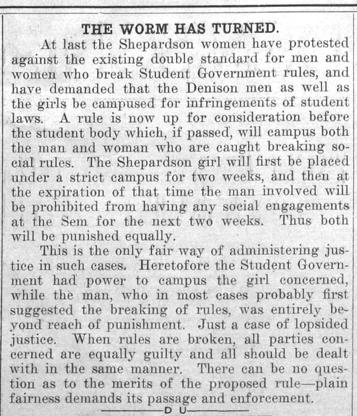

Gender roles were of course carefully prescribed at that time, but the changed circumstances of 1918 were actually opening up new opportunities for the women, including publishing the Denisonian and Adytum, and to read the editorials in the Denisonian is to witness a somewhat uneven growth spurt for the Semites. They were frivolous, playful, and flirtatious, but at the same time increasingly less shy about voicing their grievances and defining their own potential.

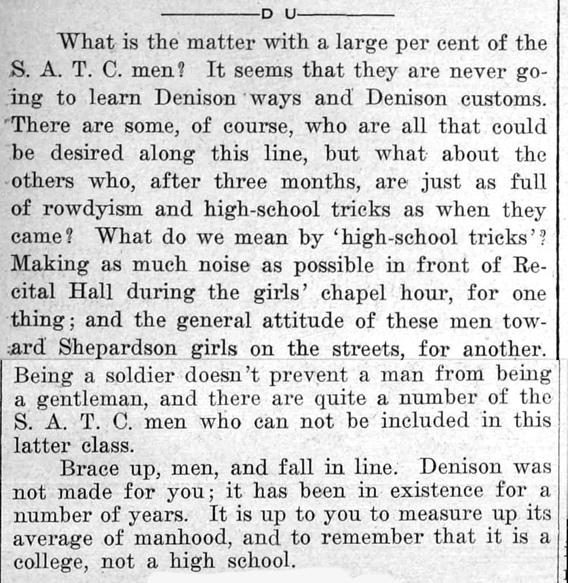

Many women felt marginalized by the war emphasis and S.A.T.C.’s takeover of both the campus and the attention of the men. They also saw themselves as protectors of tradition and civility at a time when “soldiers” thought they could get away with bad behavior.

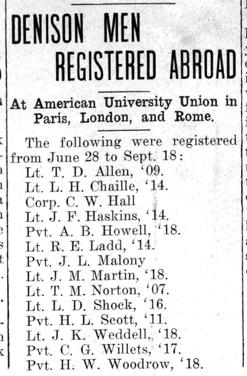

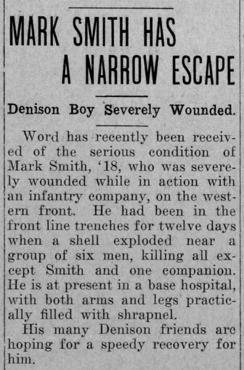

By the start of November, the front page of the Denisonian began to reflect the realities of the war: Denison men arriving in Europe, Denison men missing in action, escaping the enemy, and more and more Denison men losing their lives.

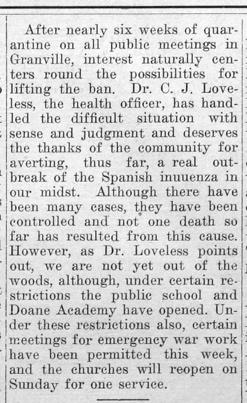

Fortunately, the losses in Europe weren’t being matched by losses at home, at least in Granville. After a month and a half of quarantine, there were still no deaths from influenza, unlike so much of the country. It was clearly to Granville’s advantage to be located off the beaten path in those days, and also fortunate that the local health officer, Dr. C.J. Loveless, was holding to the quarantine and giving sensible advice.

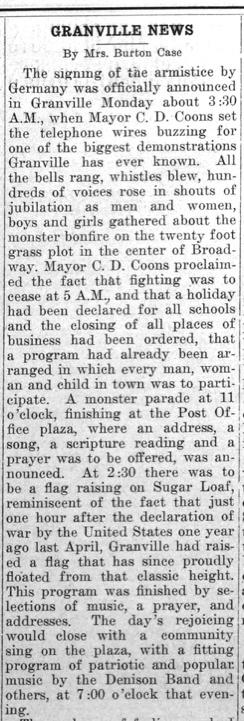

At the same time that flu update was being written for the Denisonian, the Armistice of November 11, 1918 was signed between the Allies and Germany, and the great event was reported by Mrs. Case.

As abruptly as Denison had adopted the many changes required by the war and the flu two months earlier, plans were adopted to disband the Student Army Training Corps and return the college back to its former self. While a number of the men who survived the war planned to return to Denison, most of the S.A.T.C. men were not interested in staying to pursue a college degree, and they dispersed after December.

Denison had more than 800 stars on its service flag, representing students and alumni who served in the war. Eight gold stars represented the Denison men who died.

With almost the perfect timing of a melodrama, the end of autumn term at Denison also coincided with the final waning of Spanish Influenza in Granville. The university and town were unusually fortunate, having had no fatalities, and unlike most other colleges, having no days of closing due to the flu.

Worldwide, the final death toll from the pandemic was between 50 and 100 million, 600,000 in the United States alone — claiming more lives than all the battles of World War I combined.

A final coda for the women of Shepardson, who worked and waited and ate ice cream at Casey’s while the boys had their war. As the men returned to campus and reclaimed their old turf, from housing to journalism, the women found their voices. Go back to the expectations for women before the Armistice of November 11? Not likely. Tolerate punishment unequal to the men for social offenses (especially when it was so often the men’s idea to break the rules)? Not anymore. The worm had turned.