If it weren’t for the tenacious prodding of his gut instinct, Thomas Cummins ’73 would not be at Los Angeles’ Getty Museum right now on sabbatical studying one of the only three existing manuscripts on Inca culture. He wouldn’t be hunched over a fiber-optic light uncovering thousands of pages of written and pictorial stories from 1660 that reveal the culture, art, politics, and social morés of Peru during and after Spanish colonization—illustrations that include the Spanish beating the Indians, the Inca crying big, round tears as their leaders are executed, and a progression of native kings posing—their eyes filled with pride and sadness.

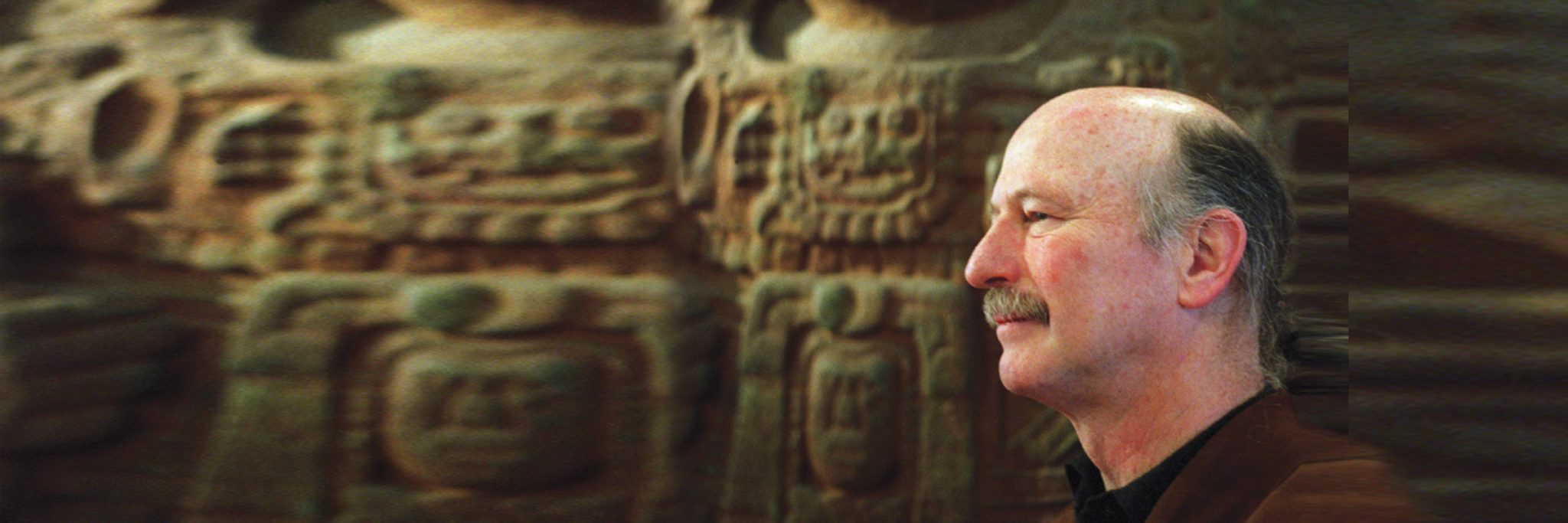

“Everything I have ever done has occurred by happenstance, by experiencing things. If I have a hunch that there might be a story behind a painting or artifact, then I can’t let it go. I am just swept up,” says Cummins, the Dumbarton Oaks Professor of the History of Pre-Columbian and Colonial Art at Harvard University.

At Denison, Cummins abandoned study of American art after spending a year in Bogotá and Peru. Then—thanks to funds and opportunities through a professor—he spent two months traveling through Panama in a dug-out canoe cataloguing artifacts and then studied the rituals of the Cuna Indians with another professor who was making a documentary. In grad school at UCLA, he was nearing the finish line of his dissertation on Medieval European art when he realized life was too short to devote it to art that didn’t truly move him. “You have only time in your life,” he says. “You might as well wake up every day and do that thing that keeps rattling inside you.” So, he started over. He learned Quecha, the language of the Inca, and he and went from there.

Back at the Getty, he is delving deeper into his main interest: finding and interpreting objects that offer a richer understanding of the relationship between the Aztec and Inca people and their Spanish conquerors. That involves interpreting their pre-colonial forms of written communications, made up of geometric abstractions and notations and knotted cords laid out in a non-linear system. “The speed at which the forced transition from the non-pictorial to the pictorial in these cultures during colonization is astounding; fewer than 50 years,” he says. “I want to know why things happen, and how, what a culture wants and does.”

One question of late that he can’t answer with his gut feeling is why he was chosen as the model for the Tom Hanks character in the 2006 film, The Da Vinci Code. “I got this weird call,” he says. “Out of the blue.” Cummins claims he barely thinks about his clothes and has no idea if they are quintessentially professorial or not. “That I am in academia at all surprises me—and most people who know me—since I was such a horrendous student in school.” But, as he will attest, being open to that intuitive feeling low in your gut, takes you places—even far back to pre-colonial South America.