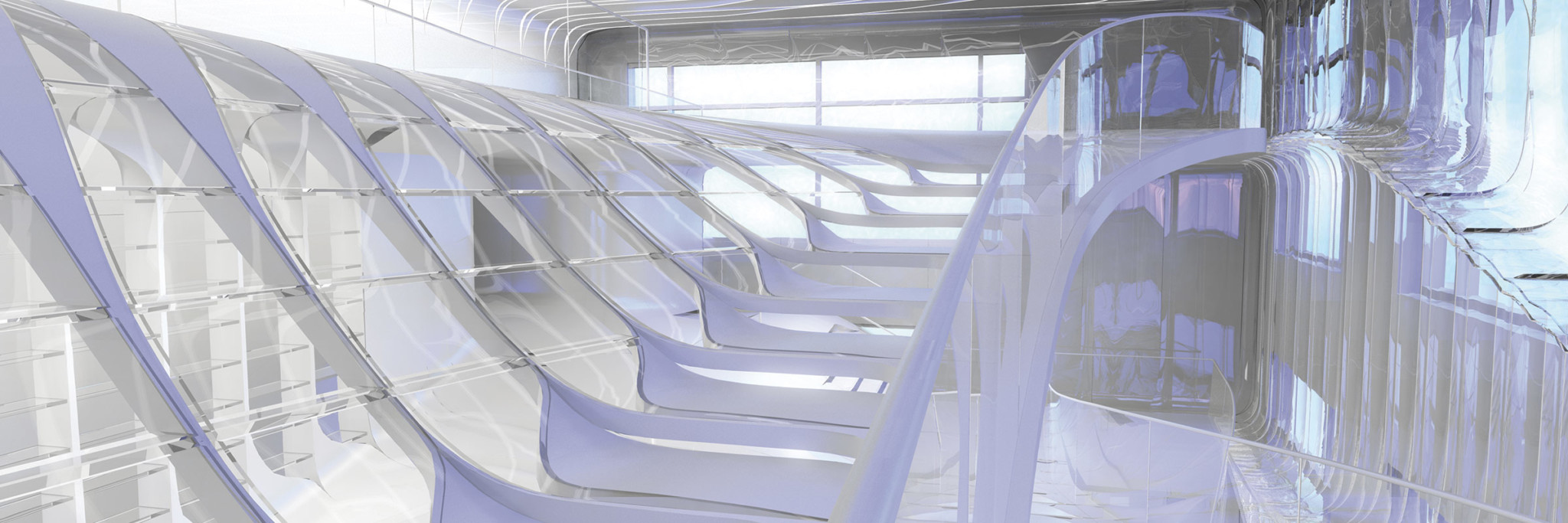

The Reebok flagship store, designed by Jamelle, sits in Shanghai, China.

Hina Jamelle ’93 used to be a painter. Tucked away in one of the many art studios in what used to be Cleveland Hall, Jamelle, a double major in studio art and art history, painted on huge canvases. “If they were to get any bigger,” she says, “they would be three-dimensional.” It turns out that those 8’ x 8’ canvases aren’t actually that big compared to Jamelle’s more recent projects, such as her design for a residential housing tower in Dubai that was completed in 2008. Dozens of stories high, the swirling mammoth of concrete and glass takes up an impressive 463,000 square feet.

Her work, it’s safe to say, has entered the third dimension.

After receiving her Master of Architecture degree from the University of Michigan in 1997, Jamelle joined the Contemporary Architecture Practice with partner Ali Rahim in New York City in 2002. In the subsequent nine years, the duo has worked on design projects internationally and cultivated a far-reaching reputation for elegance and precision. Their work often relies on a seamless blending of new, cutting-edge materials (polymers) with the tried-and-true (concrete, glass); they depend on digital technology both in the design and manufacture of their projects; and they think just as much about how the client will live, move, and interact with others in their designs as how the designs actually look.

“We have a very rigorous goal,” says Jamelle, “which is what I always call ‘a pursuit of elegance.’ I would define elegance as refinement, precision, and formal opulence, and these three things are really key to our work.”

Contemporary Architecture and Jamelle are perhaps best known for two major projects—the Reebok flagship store in Shanghai, China, and that Dubai housing tower. These designs were the first to bring international recognition to Jamelle’s work.

“Those two projects took on a life bigger than us,” Jamelle says. They got a lot of people talking, and earned the pair plenty of awards and international publicity. Plus, Jamelle says, the projects helped her and others in her office hone their techniques and question how they could push themselves further as architects.

In other words, they couldn’t keep doing the same things over and over again. “You have to look forward,” says Jamelle. There are certainly commonalities in Contemporary Architecture’s work, but there are other aspects that are ever-evolving.

One important element of the work, for example, is the fusing together of each “layer” of a design. “Usually, you could take away the structural systems or the lighting systems without the integrity or design of a project changing that much,” Jamelle says. “In our projects, we try to integrate design and spaciality with the building systems, so you can’t take away any component… I love it when people say, ‘Wow, your projects looks so effortless,’ because it takes many, many iterations to get all of those systems to begin to work together, to influence each other, and work spatially.”

These days, Contemporary Architecture is working on ongoing projects with clients in Japan, Brazil, and Korea. “Usually when clients come and see us, they want something that is an icon or something that is very unique or a design that will bring their brand or business to three dimensional life. Essentially they want something that has never been done before.” To quote that Japanese client, “Can you do better than your design for Reebok?”

Aside from her office’s projects, Jamelle has been on the design faculty of the University of Pennsylvania for the past seven years, where she leads graduate design studios for students in the Master of Architecture program.

Her office is in SoHo in lower Manhattan, but Jamelle calls a loft in Tribeca home with Rahim. As the living space of two architects, there are certain expectations visitors have upon entering. “It’s a very sleek, modern loft,” says Jamelle. “People wouldn’t want to see something traditional, something completely different from our work. I don’t think they’re disappointed.”

A 13’ x 8’ x 8” replica of their work,“Migrating Formations,” which was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art for their show Home Deliveries in 2008, shares space in the loft with several of Jamelle’s paintings from her days at Denison. “It’s a great canvas for them,” she says, “but I look at them, and I almost don’t know who that person is. I do … but I don’t. It’s been a long time.”

A lot may have changed since her days on the hill, but the desire to create is one constant part of Jamelle’s life and career. “Time permitting, I would love to go back to painting,” she says. “I think the work would be very different now.”