“A Million Dollar Year,” declared the Granville Times headline, looking back at 1924. It had been a pinnacle of development in Granville, which only three years earlier introduced electricity into village homes, and five years before that installed the town’s first sewer system and began paving its notoriously muddy village streets.

Civic pride and building projects flourished following these improvements, and 1924 brought big changes to the village as well as the completion of Swasey Chapel on Denison’s campus. But no change was as transforming to the appearance and spirit of Granville as John Sutphin Jones’ Granville Inn and Golf Course.

J.S. Jones’ life was a true Horatio Alger story. The son of coal mining Welsh immigrants in southern Ohio, he pursued a career in the railroad business that brought him to Granville. There he met and married in 1884 the well-to-do Sarah Follett, who lived with her parents in Monomoy Place. Jones’ dealings in railroads and coal mines eventually earned him substantial wealth, allowing him to indulge his appetite for property and fine things.

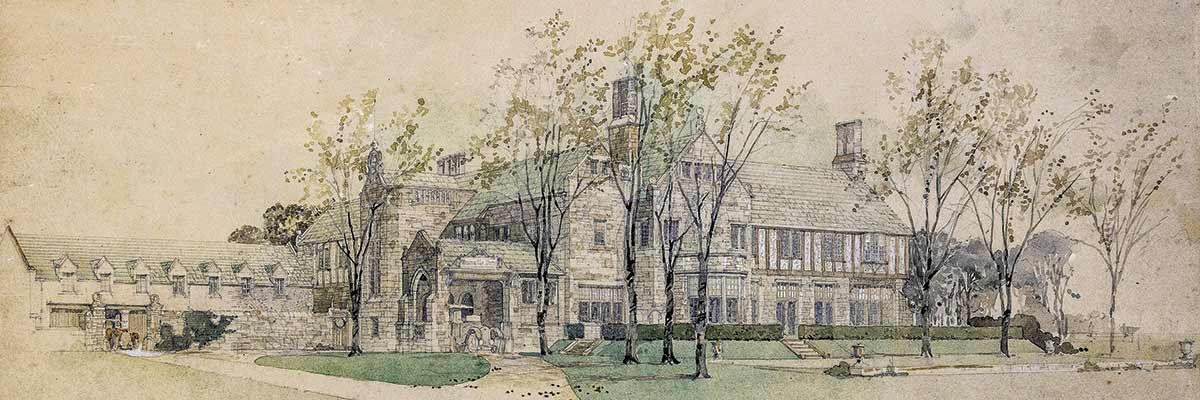

In 1908, while still in the midst of creating Bryn Du, his sizeable estate east of the village, Jones purchased the land across the street from the Buxton Inn on East Broadway. The property had served for 60 years as the campus of The Granville Female College. Prominent architect Frank Packard, who worked with Jones to design Bryn Du, returned in 1922 to begin creating Jones’ elegant and picturesque inn on this land, in the style of an English country manor house. Packard’s early blueprints name the project “Ye Purple Pig Tavern,” no doubt poking fun with Jones at their British affectations.

The idea of creating an inn was closely tied to the proliferation of automobiles and paved roads in the 1910s and early 1920s. Well-heeled day-trippers and tourists in motorcars were looking for lodging and diversion, and Jones wanted his adopted Ohio village to be a showplace.

An early promotional pamphlet for the inn and golf course includes a fold-out map showing all major roads between Chicago and New York leading to Granville, Ohio, with descriptions to tempt “the traveling and pleasure seeking public … those who know and appreciate service of the highest type,” playing up Granville’s “ancestral” trees, electric lighting, “splendid waterworks [i.e. indoor plumbing], and well-paved streets.” The west wing of the inn was designed with a walled courtyard for parking guests’ motorcars, and a three-bay garage with space for 8 to 10 Model Ts.

As Packard began designing the Granville Inn, Jones also hired the preeminent Scottish designer Donald Ross to transform the 200 westernmost acres of his estate, Bryn Du, into a first-rate golf course. The two projects shared the purpose of providing an elegant destination for motorists, while also raising the tone of the community to the tastes of its leading citizen.

An estimated 5,000 guests attended the opening reception of the Granville Inn on June 26, 1924. Facilities included 24 sleeping rooms; an oak-paneled “great hall” lobby with sofas, easy chairs, and a long library table for reading; and an “unroofed piazza” to the back with a fountain, where guests danced under the stars to Gregg’s Orchestra of Columbus. Downstairs offered gentlemen two smoking rooms, a billiard room, and a bar, whatever that word implied five years into Prohibition. Altogether spiffing. The buffet menu that evening included Lobster a la Parisienne and vanilla ice cream from Jones’ Bryn Du Farm.

The building’s cost was judged to be in the dizzying range of $600,000, and the golf course was an additional $200,000. Acknowledging its own extravagance, the inn’s brochure describes itself as “an enterprise based on civic pride without consideration of immediate profit.” The year after its opening, Editor John Willy of The Hotel Monthly magazine was lured from Chicago by the inn’s reputation for charm and comfort. He wrote, “The village of Granville, in Licking County, Ohio, is noted for having the most costly small hotel of any place in America, if not in the world.”

The inn’s high standards rested on the able shoulders of its German-born manager, Max Mehlborn and his Scottish wife Annie, who served as clerk. Mehlborn hired other German staff including Paul, the chef, and waiters like Otto Hauf, who epitomized the general atmosphere of meticulous old-world service, responding to guests with a heavily accented “very good,” and at least an implied click of the heels. Over nearly 30 years, Hauf discreetly served both local citizens and visiting titans of industry, including Henry Ford. In a 1951 interview Hauf recalled “that great lawyer, Clarence Darrow,” as well as “the day all of the governors of the United States, except two or three, came here for lunch and a day of business. This was the greatest day of the inn.”

Mehlborn’s nephew, James Young ’30, took over management of the inn from 1932 to 1951, and his son Chuck Young, who still lives in Granville, grew up surrounded by the inn and its staff, sporting dark green uniforms with crisp white striping. As a boy, Chuck was allowed (“with supervision”) to operate the inn’s plugboard phone system, dialing outside lines for the guest rooms. He remembers meeting lodgers like Admiral “Bull” Halsey and British actor Charles Laughton, who in 1949 came to the front desk looking for a shoeshine. Young was 11 at the time and watched the bellhop take Laughton’s large shoes as the actor padded off to the dining room in his stocking feet.

When John Sutphin Jones died in 1927, ownership of the inn passed to his first daughter, Sallie Jones Sexton, a horsewoman and noteworthy character, but generally acknowledged not to have inherited her father’s gift for finance. Despite receiving its first significant facelift in the early 1950s (including the addition of nine guest rooms), the inn’s future became clouded. By the early 1970s, articles about lawsuits for unpaid services started to surface, guest rooms closed and then the restaurant, and it was clear the business was in trouble.

Seriously hobbled by bills, Sallie Jones Sexton lost the Granville Inn and her beloved Bryn Du farm—the inn was sold in a 1976 sheriff’s sale to Paul Kent and his son, Robert Kent ’57 for $190,000. The Village of Granville had just voted to allow the sale of alcohol at this time, so in addition to converting the former oak-paneled lobby into a dining room, the Kents created a tavern in what had been a small sunroom behind the dining room, providing a popular gathering place in the decades since.

In 2003, the Kent family sold the inn to Granville Hospitality, a group of local investors who announced having “no big changes in store for the inn in the short term.” Operations continued as usual, with some imaginative experiments like Murder Mystery Dinners and wine tastings, but the recession was unkind to business and the facilities were sinking under deferred maintenance. In 2011, the lending bank foreclosed on the inn, citing a $1.7 million debt.

It was clear the grande dame of Granville needed more than a new gown; she needed a suitor of means, and for the next two years, she waited patiently as service continued and carpeting grew more threadbare. Denison kept its eye on the process, knowing the inn’s value to the university as well as the town. A stimulus to the local economy and setting for countless occasions, it was also a uniquely fine place to lodge and entertain visiting guests, from Robert Frost to Leontyne Price—lecturers, job candidates, prospective students, parents of students, and of course, alumni.

With all this in mind, Denison’s trustees together with Seth Patton, Denison’s vice president for finance and management, researched the building and the business and saw an opportunity to do the right thing for the college and the town. Convinced that the inn can be run as a “vital and successful business,” Denison stepped in and purchased the Granville Inn for $1.25 million in September 2013, closing its doors the following August for a nine-month, $9 million renovation (federal and state historic restoration tax credits will offset that cost by $2.6 million). Under a plan to retain the character of the historic inn but to bring its infrastructure and functionality into a new century, every square inch has been painstakingly refreshed from top to bottom.

Rough attic space on the third floor has been converted into new bedrooms and suites, bringing the total number of guest rooms to 39. Bathrooms and kitchen are completely renewed, as are all of the building’s systems, from wiring to wireless to HVAC. An elevator has been added, and the carriage house where Model Ts once parked is now a dining space with outdoor tables. The former pub and dining room have traded spaces, making the large oak-paneled “great hall,” originally the lobby, into a tavern. Friends of the inn will be reassured to find that the characteristic details they associate with the original architecture have been preserved, in particular the oak woodwork and leaded- glass windows.

Almost as if J.S. Jones were still keeping his hand in Granville affairs, the shareholders of the Granville Golf Course, including former inn owner Robert Kent, approached Denison last year offering the course as a gift to the College. Trustees voted to accept the gift in October 2014. After some sprucing-up, the renamed Denison Golf Club at Granville opened for business in April. Work on the inn is coming into its final stretch, and the plan is to be ready for guests by early May. Ninety-one years after Jones’ visionary gift to the community he loved and improved, ownership of his two elegant destinations is once again in the hands of a single, able steward.