Songs of Love

Heather Rhodes, a neurophysiologist and assistant professor of biology, believes frogs can tell us a lot about love. And it all comes back to hormones. In humans, there’s a family of them that includes vasopressin, which is involved in social signaling, and oxytocin, a hormone released during intercourse in both men and women that contributes to emotional bonding. (It’s also released during childbirth and breast-feeding to contribute to bonding between mother and child.)

Seems frogs have a similar pair of hormones, vasotocin and isotocin, and they’re just one amino acid different from their human counterparts. “Vasotocin seems to increase the frog’s motivation to reproduce,” says Rhodes, “so the male frogs call a lot more when the levels of this hormone increase.”

These calls are used primarily to advertise for females. But Rhodes and her student researchers think there is more to it, based on lab experiments. “I injected a male frog with vasotocin when he was alone,” says Rhodes. “That did not change his behavior. I tried giving vasotocin to a male when he was in the presence of a female; that did not change his behavior. But when I gave vasotocin to a male in the presence of another male, he went crazy and started calling like mad.” The experiments tell Rhodes that the frog species she works with, African clawed frogs, may be calling as a way to advertise to females, but also to yell at males nearby. “I don’t know how to interpret that yet,” she says, “but I think they’re working out some social dynamic, and it may be about who’s going to have access to a female, if one comes along. As if they’re saying: ‘It’s gonna be me.’”

So what does it all mean? That hormones do a lot more than we think when it comes to controlling our social relationships. Says Rhodes: “We like to think we have more free will than our hormones really allow us.”

When Sparks Fly

Some people really do have chemistry.

Think of it this way. Boy walks into club. Sees girl. The pheromones she’s releasing bind to receptors within his body—proteins that share complementary charges and shapes. “It’s molecular attraction,” says Sonya McKay, associate professor of chemistry. “It’s like when you cuddle with somebody, and it fits just right.”

“If pheromones play a significant role in human attraction, it’s because one person’s pheromones only “cuddle” effectively with the receptors in certain other people’s bodies,” says Peter Kuhlman, associate professor and chair of the department of chemistry and biochemistry. “That chemistry causes a cell to release neurotransmitters that then influence a whole bunch of additional cells.” It’s what McKay likes to call a “molecular cascade.”

Before the boy and girl know it, their serotonin and dopamine levels increase from all the activity. His face flushes. Her hands sweat. His heart beats faster. Now she has to ask him to dance.

Ding!

According to Cody Brooks, associate professor of psychology (not pictured, by the way), it’s your brain—not your heart—that makes you want to strike up a conversation with that handsome guy at the coffee shop. Think about Pavlov and his dog, says Brooks, whose research focuses on Pavlovian conditioning. The dog didn’t salivate when Pavlov rang a bell just because he was hungry. He salivated because the bell told him food was on the way, and reward areas in his brain were stimulated at the prospect of a meal. The same can be said for physical attraction and sex. Certain physical features can trigger complex signals in the brain that tell the body that something big is about to happen. In other words, curvy hips or beards or bare feet—whatever floats your boat, really—can get people excited at the prospect of sex (and on another level, at the idea of perpetuating the species) much like Pavlov’s dog got excited for his kibble at the sound of that bell.

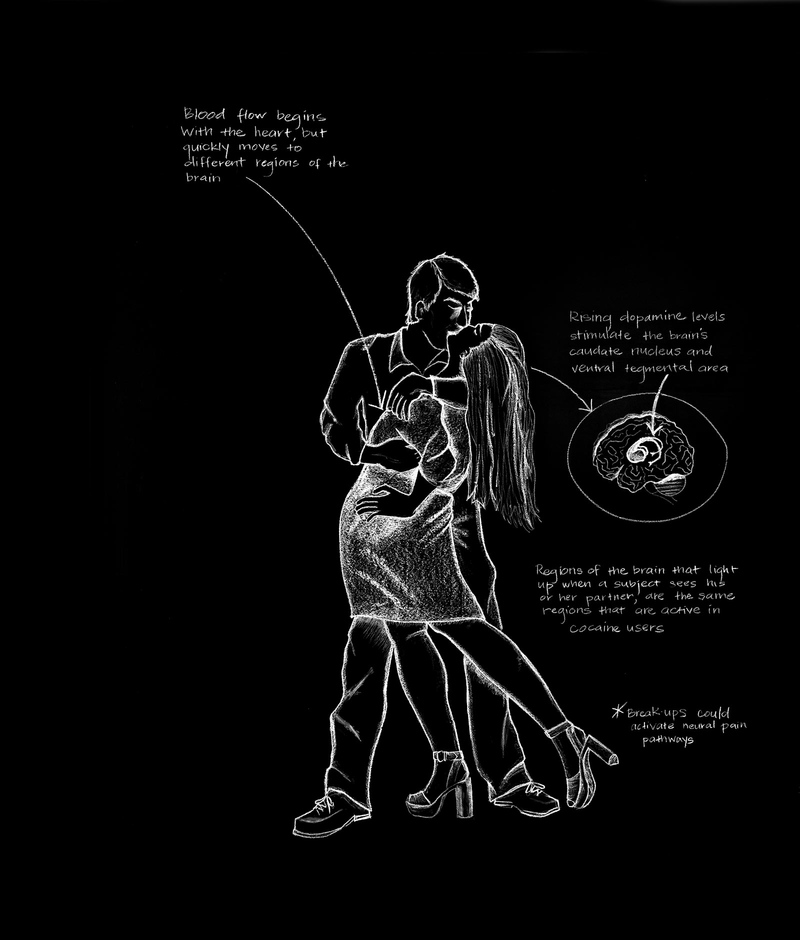

Maybe Valentines Should be Brain-Shaped

Susan Kennedy, associate professor of psychology, is teaching her advanced neuroscience students about what goes on in the brain of someone who is head over heels. She references a study in which people who described themselves as being “in love” were placed under a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine, which measures blood flow to various regions of the brain.

The subjects were shown a series of pictures, including images of their partners. Two areas of the brain were consistently active when subjects saw their loves: the caudate nucleus and the ventral tegmental area. The scientists who conducted the study, Helen Fisher and Lucy Brown, inferred that the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is involved in pleasure and reward, was responsible.

“These findings are not to say we’ve located love,” Kennedy says, “but we’re looking at areas of the brain that respond to stimuli. Clearly love is more complex than that, but the brain correlates to everything we do. Why should love be any different?” The brain scans also revealed that the areas ablaze during love are the same regions that are active in cocaine users. “The feeling you get from love is the feeling you get from a powerful drug,” says Kennedy. “It can take over your life.”

The good (or bad) news is that nobody is safe from Cupid’s arrow. “We all have the hardware in our brains for addiction,” said Kennedy, “whether it’s shopping, drugs, or love.”

Kennedy says there is way more to learn about love through neuroscience. For example, studies have shown that the longer a relationship lasts, the less these brain regions are active, sort of like developing a tolerance. And one new study suggests that break-ups activate neural pain pathways (which lends some credibility to ’80s power ballads).

“Maybe someday,” Kennedy says, “the brain will be the symbol of love and Valentine’s Day, instead of the heart.”