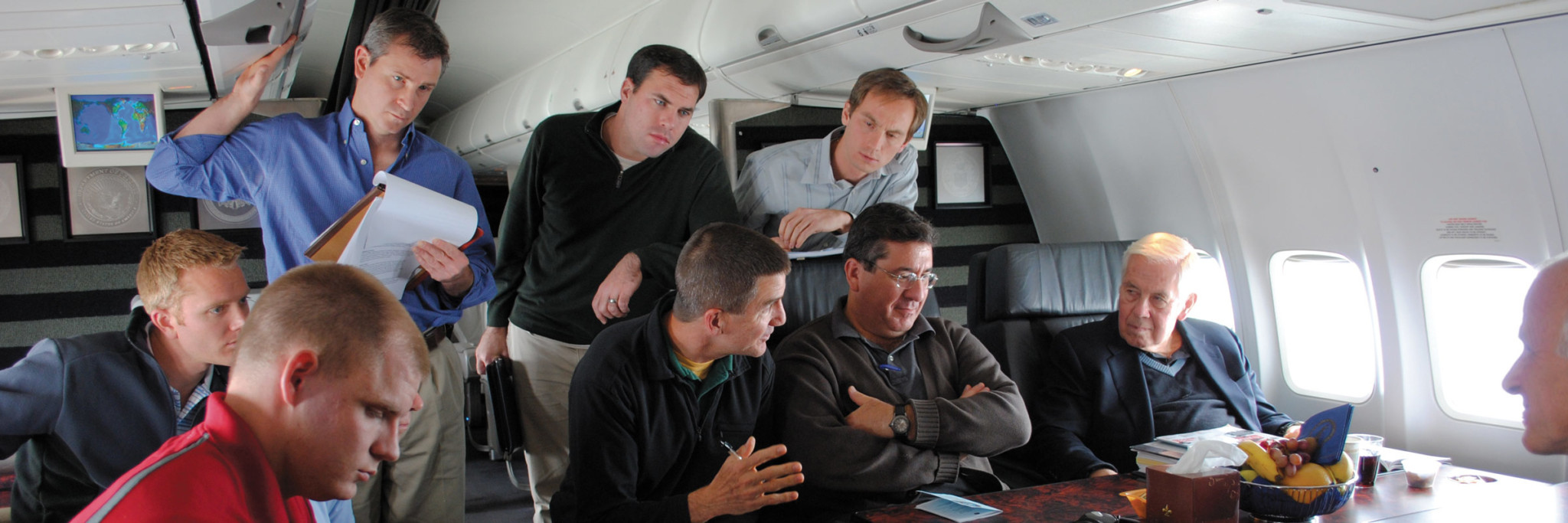

Senator Richard Lugar (seated, back right) and Grant Hartonov (at left in fore- ground) traveled to Africa on behalf of Nunn-Lugar Global, a program that evolved out of the senator’s work with the former Soviet Union.

Thousands of assault rifles and shoulder-launched missiles piled into heaps in the heart of a residential neighborhood. Vials of deadly diseases stashed in ordinary refrigerators and protected by nothing more than a few strands of barbed wire.

These are just some of the things that Senator Richard Lugar ‘54, the ranking Republican member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and Grant Hartanov ‘08, a former Lugar staffer who now works for the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, saw on a trip to East Africa last November.

The weeklong tour of weapons caches and biological research facilities was carried out under the aegis of Nunn-Lugar Global, an outgrowth of the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program that Lugar and his Democratic colleague, former Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia, founded in 1991 to secure and destroy loosely guarded stockpiles of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons in the former Soviet Union. The program was so successful–having nearly completed the deactivation of the 13,300 nuclear warheads declared by Moscow–that Congress voted to expand its reach. Now, Lugar is applying his model of neutralizing potential threats to America and its allies in places like Uganda and Kenya, where endemic diseases could be used as weapons by terrorists; and Burundi, where large stashes of conventional weapons left over from internal and regional conflicts could easily fall into the wrong hands. (The Burundi visit was technically part of a related program that Lugar founded in 2005 with then-Senator Barack Obama.)

Lugar and Hartanov visited the Uganda Virus Research Institute in Entebbe, a facility that houses the Ebola and Marburg viruses–lethal hemorrhagic fevers with no known cure–behind a gate with a simple padlock. In Nairobi, they visited a lab where researchers deal with anthrax and rift valley fever. The lab shares a wall with a shack in KiBera, the city’s largest slum–and a known recruiting ground for terrorists. And in Burundi, they saw piles of weapons that would make attractive targets for terrorists seeking to harm American and allied troops– including Soviet-built FAB-250 bombs that could be used to construct improvised explosive devices (IEDs) like the ones deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and rocket- propelled grenades similar to the ones used by Hamas.

But while guns and bombs can be destroyed or disarmed (Lugar himself crushed a Chinese-made T-56 assault rifle with a hydraulic press), the biological materials in Uganda and Kenya are a different matter. The African labs that house them seek to do no harm, but good; their researchers are struggling to better understand diseases that occur naturally throughout the region, in hopes of defending against them. “These are very responsible scientists and doctors who are doing some excellent work. The dilemma here is that they have modest facilities,” Lugar says, add- ing that they lack sufficient funds to hire enough staff, let alone secure their highly contagious contents.

Yet the intentional theft or accidental release of such dangerous bugs could wreak havoc both at home and abroad; witness the anthrax attacks in America in 2001, and the worldwide H1N1 flu pandemic of 2009.

In the long run, Lugar hopes to see increased cooperation between African labs and American institutions like Walter Reed Medical Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratories on both continents could share germ samples and engage in “a much more vigorous exchange of medical and scientific personnel,” with African scientists receiving advanced epidemiological training and their American counterparts getting a better sense of exactly what’s brewing in Africa’s biological hot zones. Such activity might also encourage pharmaceutical companies to develop vaccines against some of these superbugs.

In the short term, however, the goal is simple: to ensure that the African labs are secure, and that the people inside them are safe from both external and internal threats. As a first step, the program aims to erect proper fences around the facilities. Over time, additional upgrades like reinforced windows and proper HVAC systems will also be made–all of them designed, Hartanov says, “to keep the bad guys out, and the bad stuff in.”