Stretched out on the floor of Barney-Davis Hall and three hours into a Saturday afternoon charrette, a handful of students are making final decisions about a project almost bigger than life—one that will have an impact long after their time together has ended.

Scattered before them are floor plans they drew. When it’s time to put the plans into action this summer, they will carve a large hole into a hillside. They will line the earthen walls with discarded automobile tires and ram soil into the openings. They will raise trusses and nail together boards. They will erect a wall of windows on the south side. They will smooth stucco on surfaces and corners. When the project is complete, a new cabin—or, as some will call it, an earthship—will stand in the remote corner of Denison’s campus known as the Homestead, itself a 28-year-long (and counting) project in creating and sustaining an intentional community.

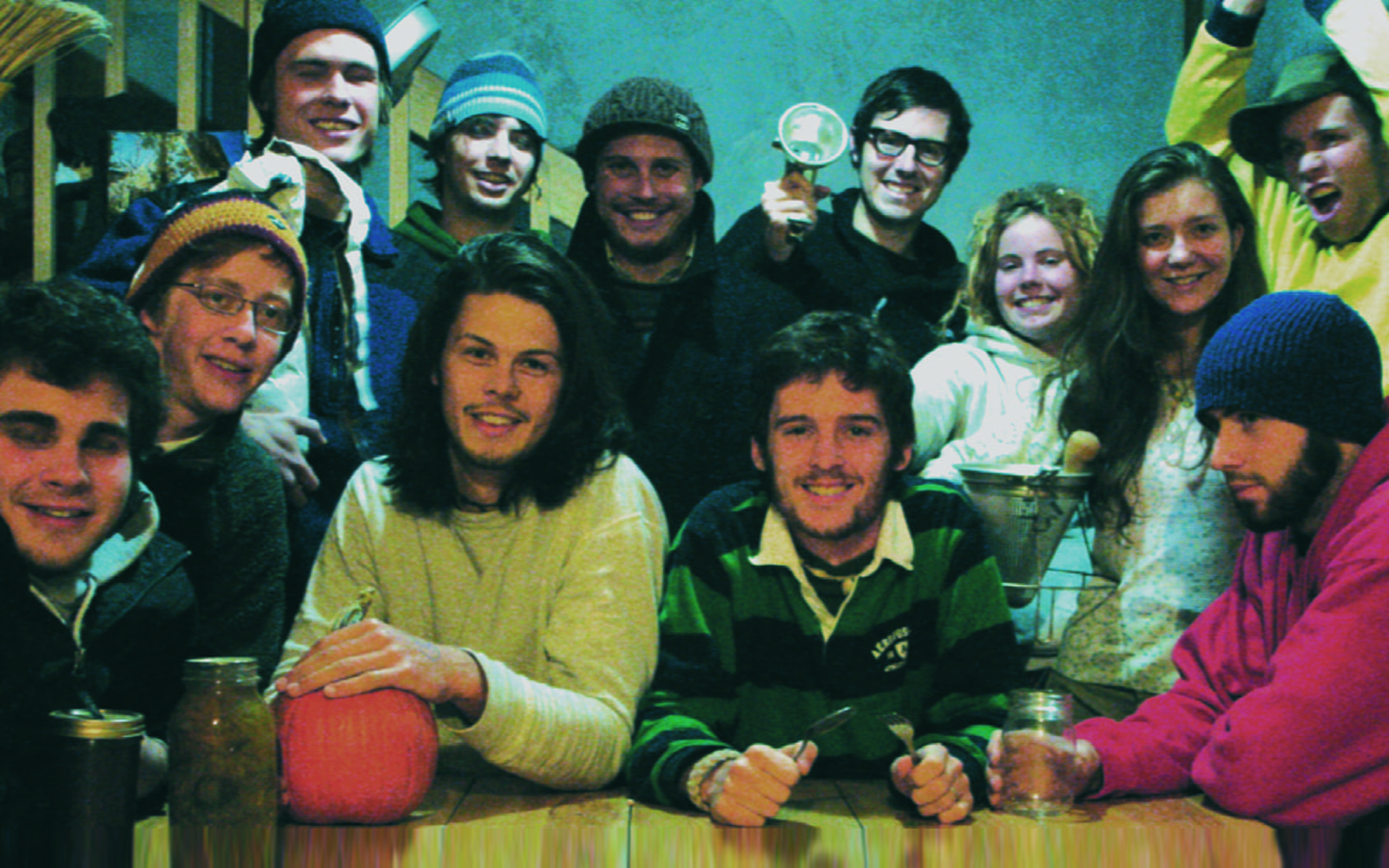

These students are not strangers to the concept of building their living space, although no one in the room has done so before. They eat, sleep, and gather in spaces built by the hands of students who lived there before them. Homestead residents, or “Homies” as they call themselves, are drawn to this alternative living experience by reasons personal, philosophical, physical, and environmental. They purposefully live with less in a quest for connections to the environment, to each other, and to life on Earth as they see it. Leaving the conveniences of residential college life behind, they split firewood, cook their food, grow fruits and vegetables, care for animals, and manage their finances. They erect windmills and wire solar panels. They construct roofs or an outhouse or bike racks out of discarded material. They discuss, debate, and compromise on how to live together and pursue the Homestead ideals of sustainability, persistence, subsistence, harmony, and the learning experience.

During the charrette, Homie Chris Hersberger ’06 motions to a sketch that shows a continuous line between the sloping ground and roof. “A roof that is a continuation of earth level is more aesthetically pleasing,” he suggests. In theory, it would be a “living roof” covered with grass and plants. To Hersberger’s left, Art Chonko, director of Denison’s physical plant and one of several interested faculty and staff present for the charrette, quietly draws a side view of the design on a flip chart. Words become walls, windows, and doors.

The discussion rolls on, toward a clearer vision of Cabin Phoenix, so named because it will be built on the site of the Homestead’s former Cabin 2, which burned down five years ago. When it’s complete, so will be another chapter in a lesson plan that, when launched more than a quarter-century ago, was only supposed to last five years.

During the 1960s, students at colleges nationwide expressed dissatisfaction with curricula that they felt were irrelevant to real-life skills. Denison’s response was the Experimental College, a program of alternative courses with small units of credit—courses like bicycle maintenance, contemporary music, and recycling, often taught by students. As environmental activism in the 1970s gained a foothold among students disenchanted with college culture and the state of the earth in general, a Denison experiment to create a democratic, agricultural-based, alternative community began. It was called the Homestead.

The brainchild of biology professor Robert Alrutz, the Homestead was a substantial undertaking. Immediate campus and community reactions to the idea were not without concerns over “disruptive counterculture,” “attractive nuisance,” and “decreasing property values.” Students living together in the woods gave quick rise to stereotypical images of drug and alcohol abuse, sexual promiscuity, and other malfeasances—stereotypes that some still hold over Homesteaders today. But in fact, no great misuses occurred, certainly no more than occur on any campus or in any other residence hall. “Homesteaders are passionate about their lifestyle and wouldn’t tolerate this sort of acting out,” assures Larry Murdock, the college’s long-time registrar. As founding students declared in their proposal, “Every effort will be made to instill principles of individual morality, community responsibility and a sense of oneness with the earth.” After 28 years, those tenets are the basis of Homestead ideals.

In January 1977, Alrutz—known fondly as “Daddy A”—and his students finalized their proposal. They requested $30,000 in start up funds, a loan they insisted they would repay in the first few years, and did. With faculty support and better community understanding, the Board of Trustees approved the project.

Construction began. Richard Downs ’77, who collaborated on the proposal in his senior year, helped build the cabins on a 10-acre parcel of Denison land across a valley to the north of the main campus. As a master carpenter and local resident today, Downs returns to the Homestead when asked to help. “In my time at Denison, we saw [northeast Ohio’s] Cuyahoga River on fire, faced the nuclear risk of Three Mile Island and witnessed civil strife caused by racism and poverty,” Downs recalls. “We lived through the Vietnam War and the Arab oil embargo. There was a feeling then, a desire to reexamine our place relative to our environment. The Homestead was a chance to control our lives just a little bit. It was the last best hope.”

The parameters set forth in the proposal guided them. They would live in rustic wood cabins. They would use kerosene lanterns for light until electricity could be generated on site; wood stoves for heating and cooking; hand-pumped water until a windmill could be constructed; an outhouse for, well, nature’s other calling. Cars would stay parked in a lot nearly one-half mile from the cabins. To get to campus for classes or a shower in the phys ed buildings, residents would drive from the lot or, preferably, walk the one-mile distance. Though gardening would begin immediately, the group knew it would not be self-sufficient for food for some time, if ever. Regular group meetings would determine daily chores, including food shopping and cooking.

As part of the experiment, the Homestead’s cabins would stand three to five years and then be torn down, paving the way for either a new generation of students to rebuild or simply to end the experiment and evaluate its outcomes—a course evaluation of sorts. But nothing was torn down. Rather, the Homestead indeed proved sustainable.

As part of the experiment, the Homestead’s cabins would stand three to five years and then be torn down, paving the way for either a new generation of students to rebuild or simply to end the experiment and evaluate its outcomes—a course evaluation of sorts. But nothing was torn down. Rather, the Homestead indeed proved sustainable.

In 2001, construction began on a new cabin for community gathering and cooking, the first large-scale building project since the original cabins went up in the ’70s and well along in planning when Cabin 2 burned in 2000. No one was injured when mishandled wood stove ashes caused the fire, but a Homestead dog and several cats died. With this new cabin, the original kitchen and eating area located in Cabin 3 could become residential space and relieve, for the time being, overcrowding created by the loss of Cabin 2. Settling for nothing less than an environmentally progressive structure, Homies researched, designed, and built a straw-bale house, one of the first of its kind on any college campus. Large, tightly packed, blocks of straw form well-insulated walls, finished off with coats of stucco inside and out. Flattened pieces of tire rubber serve as roofing shingles. It bears the name Cabin Bob in memory of Alrutz, who passed away in 1997.

Cabin Phoenix, likewise, is a progressive design in biotecture, the building discipline of sustainable, low-impact living structures and environments. The efficient and durable earthship incorporates passive solar heating and cooling using construction materials of minimal cost. Three walls are set back into the hillside, formed by used tires that are stacked and filled with a mixture of sand, gravel, and dirt. The south side is a wall of windows, providing light and heat. In southwest towns such as Taos, New Mexico, earthship communities dot the landscape and offer models for those interested in alternative construction methods.

Hans Gorsuch, who plays an advisory role as Homestead coordinator, is building his own earthship in Canal Winchester, less than an hour from Denison. During the charrette, he offers first-hand advice from his own experiences. He listens to students find common ground and helps them envision the structure. “An earthship is shaped in U’s or circles, a very specific design with all kinds of advantages and disadvantages.” Porches, living roofs and lofts can be incorporated, but it gets complicated. An earthship is well suited for a greenhouse because the south face is glass, but a voice from the group notes the old greenhouse in the lower level of Cabin 3 creates too much humidity for those living above it. How can we adjust for that? students wonder.

The bottom line, Gorsuch warns, is that construction won’t be easy. The remoteness of the site, the heavy physical labor, and perhaps some unforeseen complications will test the Homies’ passion to do the work. Insurance money from Cabin 2 will provide necessary funding; spirit and stamina will do the rest.

On a Monday afternoon in the fall, seedlings sprout in the Cabin 3 greenhouse—young vegetables to help replace summer’s fresh garden produce. A rabbit sits in his pen enjoying the warmth of the room. Outside, Homestead cats watch for arrivals as the dinner hour draws near. One perches on the compost bin just off the path. Molly, the dog, lies ready to sprint off the porch of Cabin Bob to greet anyone passing under the iron archway that serves as the unofficial entrance to the compound.

The Homestead’s cluster of buildings include Cabin Bob, Cabins 1 and 3, a tool shed, a well-fed solar shower that’s used primarily in the warmer months when the sun can heat its water, and an outhouse that literally sparkles in the sun. Rebuilt as an Earth Week project in 2004, it bears a playful elegance with walls of amber, green, and clear glass bottles and shiny aluminum cans that catch the sun. In contrast—sitting just about two dozen feet downhill—large, flat, dark squares of high-tech photovoltaic cells aim towards the sun and remind visitors that the Homestead is progressively off the grid, much like its residents.

A closer gaze around the grounds reveals many subtle stories. A well-scorched bonfire pit, framed by colorful plank benches and large logs, whispers of music-filled evenings with friends. On the porch of Cabin 3 are a collection of weathered signs and sculptures, worn chairs and a couch—lasting contributions of former residents. There’s the old windmill top propped against the lower storage wall of Cabin 1, the A-frame of that same windmill standing as the compound’s entrance (and another nod to Alrutz). Beside Cabin Bob, a few tomatoes cling to wilting vines amid the ragged remnants of the kitchen garden, where this year’s success story was the harvest of Jerusalem artichokes. Surrounding the Homestead are other older and overgrown gardens, fruit trees, spotty stretches of post and rail fencing, patchy farm fields, quiet woods, and a small stream.

Inside, the cabins have stories to tell as well. Some are told quite literally, like the scores of posters, inscriptions, and etchings found on the walls and ceilings. Over time, students have marked their presence and expressed their passions with their own words as well as the likes of Jack London, Bob Marley, Lao Tse, and Ché Guevara. From London’s weighty I would rather be ashes than dust credo to a Homie’s suggestion to (written above a coat rack by the door), the writings connect past to present. With thoughtful respect and when they feel like they can contribute in a profound way, they etch their history on those walls.

David Strong ’06 sees Cabin Phoenix as an important new chapter in the Homestead’s history. He’s anxious to see it come together, and he’ll stick around after graduation to help with construction. A three-year resident of the Homestead with key interests in sustainable agriculture and recycling, he knows now that the place is about much more than building, cooking, and cleaning. “I hadn’t realized how much of a social experiment this is, too. For better or worse, we all need to be on the same page. We live together and try to make one thing work: the Homestead,” says Strong.

Learning is subtle and complex, operating on many levels. It continues to be an experiment in communal living, voluntary simplicity, sustainability, and self-governance, explains Homestead coordinator Hans Gorsuch. He is in his third year of the 10-hour per week resource position created several years ago to ease the impact on the Homestead where continuity is a challenge, not unlike any other student organization whose membership is continually rotating. As time passes, Gorsuch bears more and more of the institutional knowledge about how things work. But he doesn’t see himself as the Homestead’s teacher-expert. “In truth, the attractiveness of the job for me is that it gives me a chance to learn about things I’m interested in right alongside them,” he says.

Making the Homestead work begins with who becomes a Homesteader. Interested applicants visit, apply in writing, and provide recommendations. Their acceptance is determined by current residents. “Homestead students are very thoughtful, very respectful of those interested in living there,” Gorsuch says. They believe in equality and in an egalitarian community, and they strive to understand and build consensus. This process applies to all areas of life at the Homestead. But majority rule doesn’t keep the peace, they know, so interpersonal relations are critical, as is a willingness to review and question basic assumptions. “Sometimes there are disconnects,” Strong says. “We get busy with school, but we need to all come back each afternoon and make the community work.”

In basic ways, Homies live simply, although there’s nothing simple about their life together. Solutions often arise from necessity. “If someone forgets to do the shopping, we don’t eat,” Hersberger says matter-of-factly that same autumn Monday afternoon. The cook stove, stoked with wood he split earlier, begins to warm up Cabin Bob. Midway through chopping vegetables for a vegetarian pasta sauce, Hersberger discovers the onion bin is empty. “So how am I going to make this taste good without onions,” he calmly reflects aloud, more to himself than to his cooking mate, Zach Thomas ’07, who is busy chopping cucumbers for a salad. Laying the knife down, he looks around for a minute, then to a smaller basket hanging above and a head of garlic. The chopping continues.

Having dinner together each night is an important Homestead tradition, and taking turns cooking is part of the community code that develops and sustains the cooperation and patience to make life work. The code also dictates that cars stay parked at the entrance a half-mile away, and cell phones and computers remain turned off, partly due to energy conservation but mainly because they represent invasiveness of society that the Homestead was intended to forego. At weekly meetings, they set up and review schedules for shopping, cooking, pet care, and general maintenance.

“Their strength comes from group unity,” comments Art Chonko, Denison’s physical plant director, who admires the passions, constitution, and commitment of Homestead residents. “They all try to live the sustainable life. They’re living what they talk about.”

If the Homestead is sustained on its hill by the dedication and toil of its residents, it has sustained a place in the Denison community through somewhat different labors, yet altogether similar dedication, on the part of supportive faculty, staff, and alumni.

Interest in the Homestead experience has, not unexpectedly, waxed and waned. When it was first established, isolation was important to defining the group’s independent, alternative character. Visitors are quite welcome today, and Homies host open houses at least a couple times a year, but in past years access was limited. This isolationism made the Homestead almost invisible, and resulted in residency dips that jeopardized the experiment.

Richard Kobe ’88, now a professor of forest ecology at Michigan State University, was one of only five residents his senior year. “Perceptions of the Homestead ranged greatly,” he says. “Among friends who lived on campus, there was admiration for the idea of the Homestead and that we were willing to give up many modern conveniences and physical comforts.” Many others didn’t relate. “I remember one student visitor who seemed to be in a state of shock. I gave him a tour and in response to the solar heated cabins, the wood burning cook stove, the outhouse, the goats, the chickens…he had a uniform response: ‘I can’t believe you live like this.’”

Fortunately, a number of non-residents stepped up to lend their voice and action to the Homestead’s continuance. Mike Frazier, Denison’s director of auxiliary enterprises and risk management, has been involved with the Homestead since 1985. He said that when the college made its fraternities non-residential in 1995, other alternative housing options also came under scrutiny. And when Cabin 2 burned five years later, the Homestead was truly at risk. “After the fire there were some serious roadblocks,” Frazier says. “It took a recommitment of will on everyone’s part to keep it going.”

By the mid-’90s, an aging Alrutz had become distracted by the demands of other projects and provided less and less support. So in 1996—the year before Alrutz passed away—Frazier and others revived the Homestead Advisory Board (HAB), Alrutz’s model for dialogue between the campus and Homestead communities. Comprising faculty, staff, and Homestead residents, the HAB now meets twice a month to review and approve major physical changes to property and equipment and review curricular elements of the Homestead Program, among other things. “There’s such a spirit in this group,” says Linda Krumholz, an English professor who chaired the HAB for the past four years. “It’s a different sort of decision making group; students have a great deal of say. It’s energizing.”

The HAB also oversees the academic context of the Homestead. A two-credit seminar that meets weekly in the evenings at the Homestead is open to all Denison students and required of residents. Each year, a different professor brings new materials and perspectives to the seminar, addressing issues inherent to sustainability, the environment and the Homestead. This year, Bill Nichols, professor emeritus of English, leads the seminar with readings, research, and discussion on “Building Cabin 2.”

A few years ago, philosophy professor Jonathan Maskit taught “Sustainability in Theory and Practice,” in which he challenged students to define what “sustainable living” means. “Sustainable” is a hard word to pin down, Maskit says, and that makes it easy to bandy about. After a semester of reading, research and discussion, they applied their labors to composting toilets, greenhouses, and alternative building materials—all with sustainability in mind. “As a whole, the seminar is a way to give them an academic outlet for doing their intentional living,” Maskit says. “They love it, they really want to integrate life and academics.”

This kind of practical academic rigor and everyday hands-on work, Krumholz believes, defines the Homestead’s mission as a living-learning experiment. “They know the value of doing things for themselves. They’re really doing important work in rethinking the philosophy and politics of this country. They’re very informed about the state of the earth. They get the link. They look for answers.”

As the final hour of the Cabin Phoenix charrette rolls to a close, the living roof idea falls by the wayside: more engineering, more expense, more labor. Few are disappointed. Discussions like this focus the group and the sketch on the flip chart now documents decisions made. They are one large step closer to picking up shovels and hammers. And through strong traditions of living a simple life that is anything but simple, this generation of Homesteaders doesn’t need to be reminded that it’s not about what they take from this earth, but what they leave.

Evelyn Frolking—who spent one cold, snowy winter break years ago caring for and getting tormented by Homestead goats—lives and works in Granville. She wrote about the Newark Earthworks in the Summer 2005 Denison Magazine.