It would be easy to assume too much about Tony Lisska’s motivation in all this, but his is not an evangelical’s zeal. He simply thinks the facts speak for themselves.

For more than half of his 43 years as a professor of medieval philosophy at Denison, Lisska has, as a hobby, dug into central Ohio history, uncovering forgotten or little-known tales—the lives and work of “obscure Buckeyes,” as he calls them, Ohioans with quirky or unexpected stories to tell. Since 1991, he has written nearly two dozen articles for The Historical Times (the Granville Historical Society’s quarterly), their topics ranging from the story behind the mural at the village post office to the history of Granville’s stills (a piece wonderfully subtitled “From Corn Whiskey to Peach Brandy, With a Little Cherry Bounce on the Side.”)

One such story appears in the Fall 2002 issue of The Times. “A Backward Glance at the Forward Pass” differs from much of Lisska’s work in that it endeavors not just to tell a story, but to make a case—one for which the evidence is now a century old. Lisska spent a few months pulling together the relevant facts and anecdotes, culling items from old newspaper accounts and pre-World War I issues of The Adytum. The result is a 5,000-word argument for the Big Red’s overlooked place in college football lore as the first team to utilize the forward pass as a primary offensive weapon. The subhead? “Giving Credit Where Credit is DU!”

Lisska’s inspiration is more casual than fanatical, but his subjectivity is not in doubt.

“This was a story that, it seemed to me, needed to be told,” Lisska says now. “And, frankly, I wanted to get in the face of my Notre Dame buddies, too.”

As it does in much of college football history, Notre Dame figures prominently in the story. Decades of recycling—of news accounts, of legend, of myth—have left the Fighting Irish entrenched in the popular mind as the inventors of the forward pass, or at least as the first team, in 1913, to employ the tactic as something more than a gimmick or an act of desperation. That legend centers on Notre Dame-Army, one of the sport’s great early rivalries, and is magnified by the presence of Knute Rockne. In the Denison version, that marquee appeal and star power are matched by blowouts of Otterbein and Wittenberg and a hero’s turn from George “Roudy” Roudebush, Class of 1915, a farm boy with a lively arm.

The man who made Denison’s case can hardly be pegged as some Big Red fanatic; it seems the chance to challenge prevailing assumptions and tweak colleagues in South Bend simply promised too much fun for Lisska to pass up. But if he is something slightly less than obsessive in his pursuit of the larger sporting truth, he nonetheless remains confident in his case. Perhaps a career dedicated to understanding the motivations and influences of medieval philosophers isn’t bad training for finding clarity in more recent mysteries—in this case, decoding which team truly was the first to fully appreciate the competitive benefits of flinging a football over its opponents’ heads.

And the truth?

“I suppose Denison historians are as right as any others,” Dan Jenkins says. “Everybody claims to have some guy who [first] took advantage of the forward pass.”

Semi-retired at 82, Jenkins is arguably the most esteemed American sportswriter alive today. He spent decades at Sports Illustrated, wrote the classic football novel Semi-Tough, and now divides his time writing occasionally about golf and serving as official historian for the College Football Hall of Fame. If Jenkins can’t say definitively which college football team first mastered the forward pass, it’s unlikely anyone can.

The problem, as Jenkins implies, is that the forward pass is a bit like Memorial Day—everyone thinks he came up with it first. (The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs cites nearly two dozen cities that claim to have been the first to observe the holiday. Waterloo, N.Y., is listed as the official birthplace, but tell that to folks in Boalsburg, Pa., Columbus, Miss., or a score of other towns from Georgia to Illinois that claim to have done it earlier.)

Here’s what Jenkins, Lisska, and other historians know with something resembling certainty: The forward pass first was used legally in 1906, a reaction to a series of rules changes in that era meant to open up a game dominated by brutal, occasionally lethal scrums. But the pass in its earliest days remained something of a novelty, and a risky one at that. The ball was fatter and rounder then—Jenkins says a forward pass “looked like a push shot in basketball”—the rules limited where and how far it could be thrown, and an incompletion resulted in a turnover.

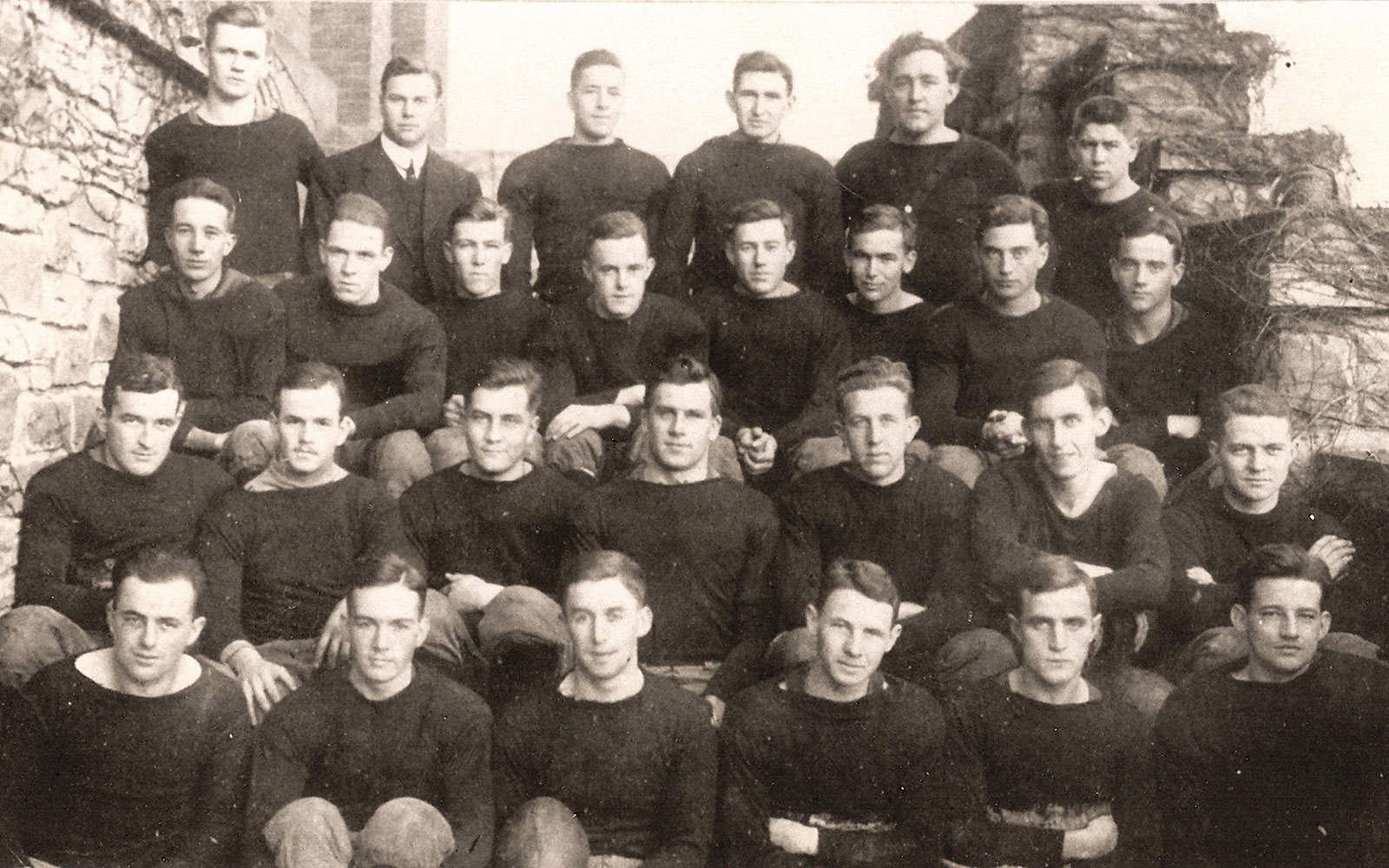

It’s generally accepted that Bradbury Robinson of St. Louis University threw the first legal forward pass in September 1906, but its use remained sporadic—and its documentation inconsistent—over the next half-decade. (Among the notable exceptions: In 1907, the Carlisle Indian School of Pennsylvania, coached by Glenn “Pop” Warner and featuring a young Jim Thorpe, made headlines by using the pass as part of an innovative attack to knock off the likes of Harvard and Penn.) But the rules changed again in 1912, elongating the ball and further easing the restrictions on when and how the pass could be used. And that’s where George Roudebush and the Big Red enter the tale.

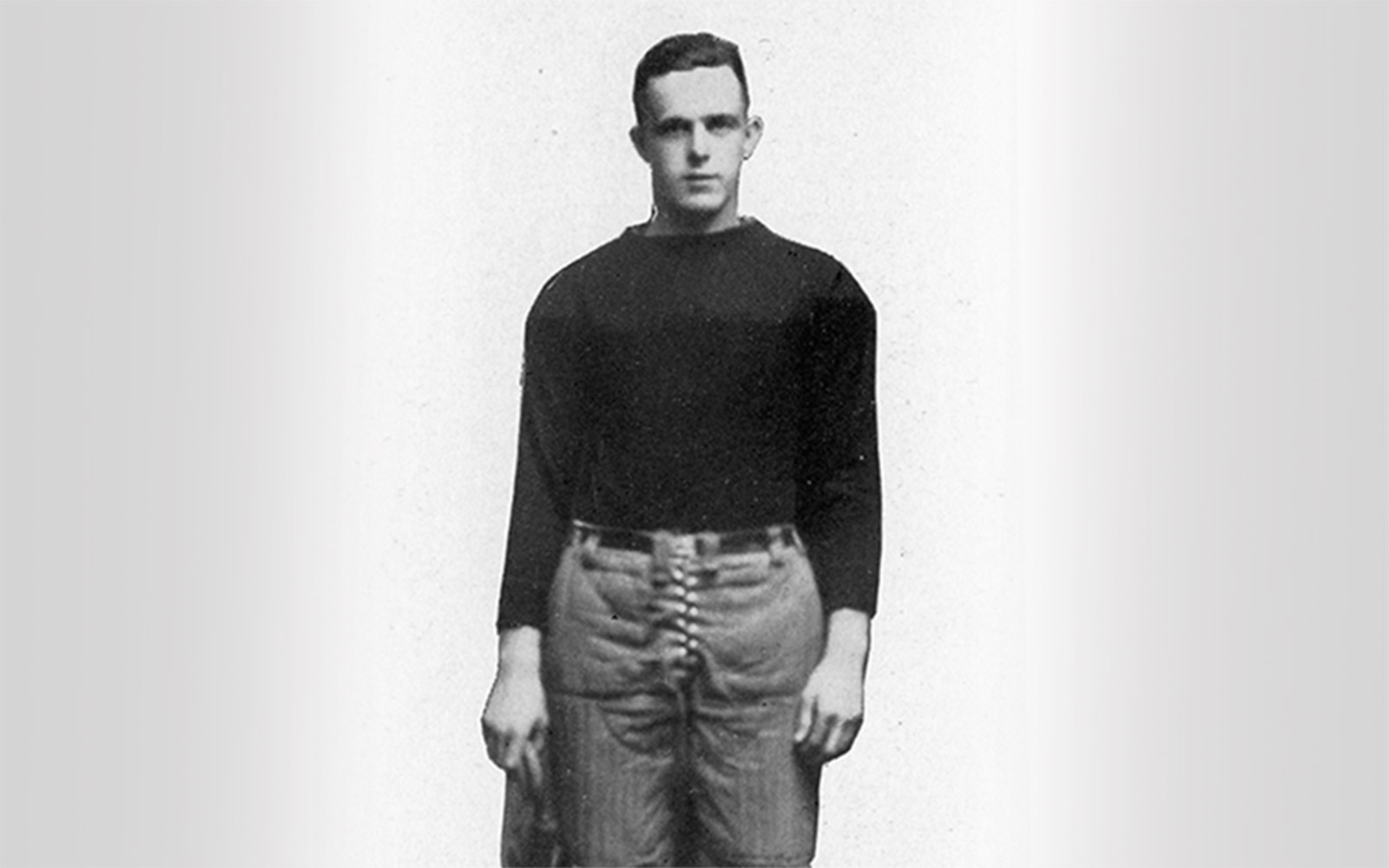

Given the limitations of mass communications at the time, it’s not hard to imagine how the rules changes of 1912—and the implications of those changes—were inconsistently received. It appears Denison picked up on their significance earlier than most. The Big Red opened the 1912 season with a 19-6 win over Ohio Wesleyan and a 34-0 loss at Ohio State. The team’s third game, a 3-3 tie with The College of Wooster, looks on paper like the most forgettable result of Denison’s season. Instead, it proved the turning point.

Wooster had the new rule book. And Wooster tried to throw the ball.

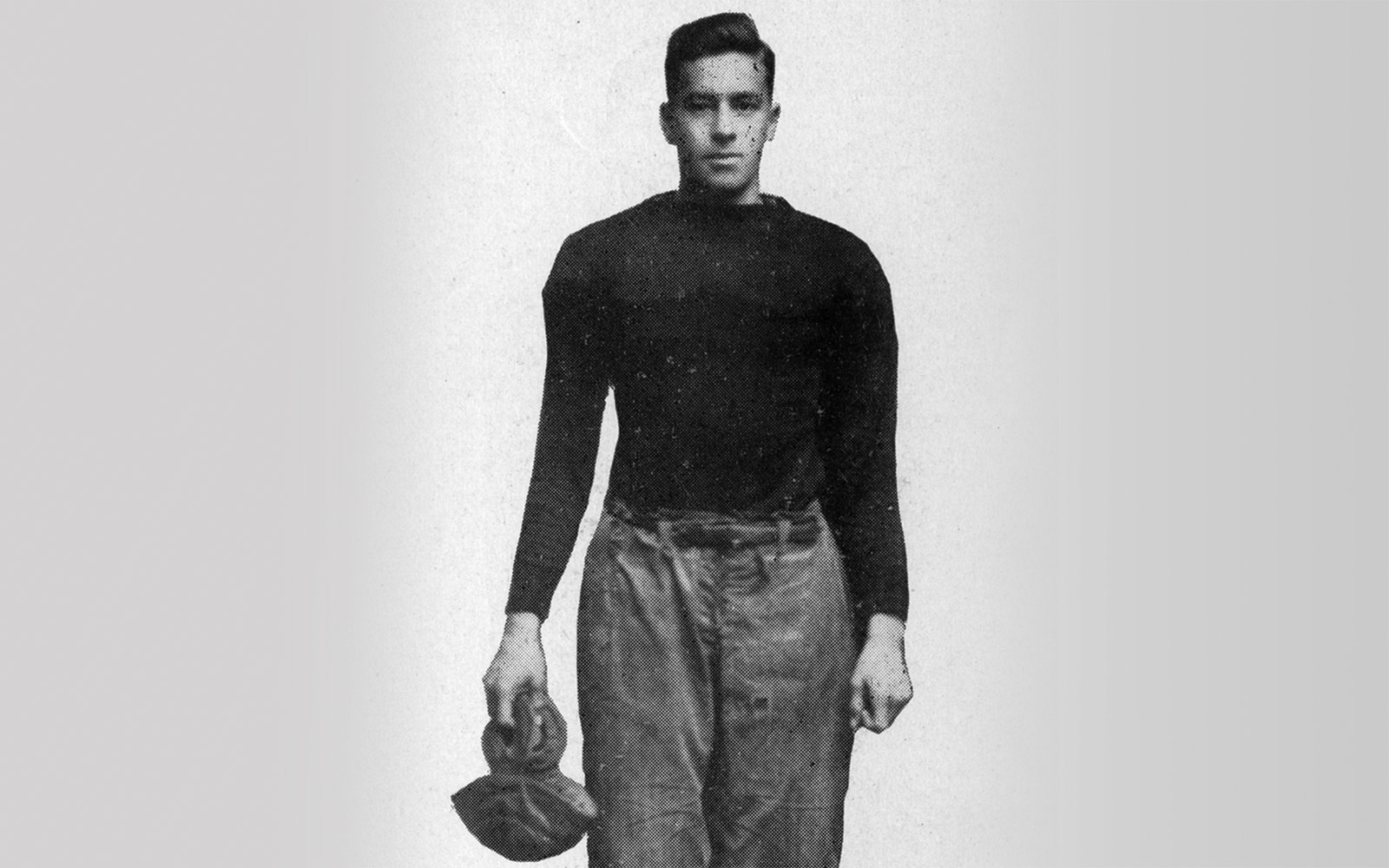

In the mid-to-late 1980s, George Roudebush sat for interviews with The Columbus Dispatch and the journal of the Cleveland Athletic Club, where he was a longtime member. A nonagenarian by that time, Roudebush reportedly was still sharp enough to go to work most days at the Cleveland law firm of Arter & Hadden. His memory appears to have held up, as well. Wooster, he told a columnist from The Dispatch, “threw the ball all over the park.” That Wooster’s aerial assault led to just three points did nothing to dampen the Denison team’s curiosity. The Big Red got ahold of the new rule book, and they saw the strategy’s potential.

Conversations among the players after the Wooster game led some of them to approach coach Walter “Livy” Livingston, Class of 1909, with a suggestion: Let Roudy throw the ball. By his own telling, Roudebush had developed a strong and accurate arm by “throwing stones and corncobs at the hogs and chickens” on his family farm in Newtonsville. There’s no telling how well that practice prepared him for flinging something akin to a modern rugby ball, but what seems certain is that Roudebush could throw. Against Otterbein the following week, Livy gave Roudy a chance to prove it.

Final score: Denison 60, Otterbein 3.

The Big Red piled it on again a week later, trouncing Wittenberg 68-0. The catalyst was Roudebush, who, Lisska writes, eschewed the “pushing” motion predominant among early passers and chose instead to grip the ball near its end and throw it with a modified pitching motion. (Roudy played baseball at Denison, as well.) Cross-sport pollination was a theme with this team: As Lisska writes, David Reese, Class of 1915, became a primary receiver because of his prowess on the hardwood, and Coach Livingston wisely realized that “a basketball player should be a good man to catch passes.”

The scores weren’t quite so eye-popping the rest of the 1912 season, but the results were the same: 31-13 over Cincinnati, 13-0 over Miami of Ohio, and 17-6 over West Virginia. Newspaper reports from the winning streak herald Roudebush’s “wonderful accuracy” and “brilliant” passing that left opponents “dazzled” and “bewildered.” It was as if the farm boy were casting spells with that arm, not simply throwing a ball.

The drubbing of Wittenberg on Nov. 2 of that year was the statistical peak of Denison’s seemingly instant mastery of the forward pass. The Big Red had shown that the new strategy could be used to flummox opposing defenses. In the boys from Granville, the exception had become the rule.

On Nov. 1 the following year, Notre Dame traveled to West Point, N.Y. for its first-ever game against Army. The Irish arrived unheralded and left 35-13 victors, toppling the cadets in an historic upset. As reported in The New York Times, Notre Dame “flashed the most sensational football that has been seen in the East this year, baffling the Cadets with a style of open play and a perfectly developed forward pass… Football men marveled at this startling display.” The Times quoted a game official who said he “had never seen the forward pass developed to such a state of perfection.”

The shock result quickly became the stuff of legend, and when asked for their side of the story, folks in South Bend today are happy to confirm it. The exceedingly helpful sports information department at Notre Dame responded to a request for the “official” story with digital reams of clippings and book excerpts, all of which support the established tale: Irish quarterback Gus Dorais and end Knute Rockne (who would go on to great fame as Notre Dame’s coach) worked together as lifeguards at Cedar Point that summer of 1913, where they spent their spare time dreaming up and practicing the passing offense that would upend mighty Army.

Notre Dame, of course, remains the only college football program in America with its own network TV deal, and the iconography of the golden domers, Touchdown Jesus, and “win one for the Gipper!” are fundamental to any understanding of the history of the sport. That 1913 game, too, has its place: In his comprehensive history, College Football, historian John Sayle Watterson writes that “Notre Dame used the pass with the length and sophistication that few eastern teams thought possible.” And in 2007, author Frank Maggio published Notre Dame and the Game That Changed Football. In the battle for a place in the public consciousness, Roudy and the Big Red never had a chance.

Tony Lisska is not naïve about the snowballing force of a good popular myth. “I think the Eastern press corps just picked it up—‘This little Roman Catholic college from God-knows-where, Indiana, comes out and beats Army,’” he says. “And of course, Rockne had a tremendous sense of public relations. He really knew how to work that.” In fact, Rockne died in a plane crash in 1931, on his way to Hollywood to assist in the production of The Spirit of Notre Dame. The legend would long outlive the man.

The story of George Roudebush and the groundbreaking 1912 team never quite reached the status of “legend.” In truth, it never got particularly close. Not that some haven’t tried to help it along.

Richard Blackburn’s definitive The Big Red: One Hundred Years and More of Athletics at Denison details the efforts of Lester Black, a captain, kicker, and tackle on the 1912 team, to set the record straight. As Blackburn writes, Lester Black made it something of a personal mission to clarify his team’s place in the historical record, writing letters to the Granville Sentinel and The Denison Alumnus in which he cited personal memories and newspaper coverage to argue the case.

Roudebush, who would chime in on the topic when asked, lived far too full a life to let the public perception of his college football career hold him back. He served with the army in World War I, played pro football after the war, and spent seven decades as a practicing attorney. The former Denison trustee and athletic hall of famer died in 1992, two years shy of his 100th birthday.

And then there is Lisska. It’s been 10 years since his essay ran in Granville’s Historical Times, and he certainly never expected it to change popular perception of the sport’s history. But he did allow himself cautious optimism that it might change …something. He says he gave a copy of the piece to then Big Red football coach Nick Fletcher, who handed out copies to his players. He’s not sure if the current football staff is even aware of the story. Efforts were made to interest ESPN in the topic, but nothing came of it.

But Lisska has no regrets. “I got a response from my Notre Dame friends,” he says with a laugh. As if knowing that they know the truth is sufficient reward.

Ryan Jones is a senior editor at The Penn Stater magazine and the former editor-in-chief of Slam, the monthly basketball magazine.