Crayons. This is clever in the way that makes you wish you’d thought of it first, while knowing that only Christian Faur could have done justice to the idea. Faur is a physicist, a mathematician, a designer, but he’s also an artist. He’s an experimenter. He uses the word “maker,” and that works too.

As the director of collaborative technology at Denison, Faur’s job is to help faculty and students in the fine arts use and combine new technologies in their creative projects. But he’s also driven to make his own objects of beauty and meaning. Like a magpie, he scavenges widely for materials, pieces of information, and ideas that interest him- and like a scientist, like an artist, he prods them and watches them interact.

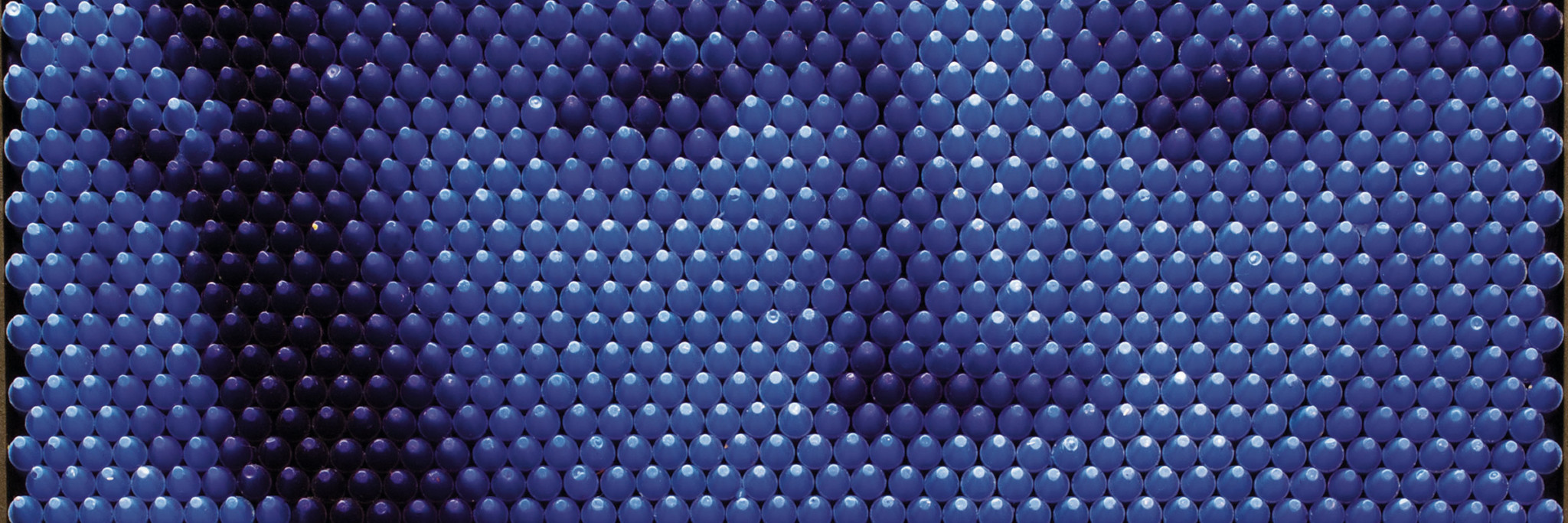

New ideas for investigation can begin with a fresh look at an unexpected medium. A few years ago, Chris picked up his daughter’s crayons and spread them out, stood them on end, and considered them closely from all angles. As in mathematics or a game, he started with parameters: the shapes of the crayons are fixed and regular, their colors and values (light to dark) are varied. As he juxtaposed these shapes and colors, he watches for a kind of visual and intellectual friction, a spark of an idea on which he could experiment. Bunching the crayons together and looking at their pointed ends, most of us would see a waxy bouquet, an array of colors. Faur, the technologist, looked and saw pixels, the fundamental units of electronic imagery. In the same way the brain translates thousands of printed dots in a digital photograph, he could imagine a matrix of crayons tightly arranged to create a coherent image.

Faur creates crayons for use in his artwork, but he doesn’t actually color with any of them. Instead, the crayons themselves become a part of each piece. Still, the process makes for a pretty colorful at-home studio.

Using handmade molds and a battery of crock pots, Chris began to produce his own crayons of resin and beeswax in a range of colors and values far beyond a Crayola geek’s dreams. This made it possible to create more sophisticated images, but more important to Faur, it gave him incredible latitude in areas of his investigation and experimentation, such as neurological perceptions of color and light (the human brain registers tone before it sees color) and the semiotics of color–a far-ranging interest he has in what different colors communicate to the viewer.

In a gallery setting you can see how the protruding crayons add an active component to his work–viewers lock eyes on seeming abstractions of color, then slowly move across the work, watching the pixels shift and resolve into images. For his first solo show in New York this past summer, he recreated WPA photos from the Great Depression as a way of addressing the national economic crisis and the effects of Wall Street on the rest of the country. Faur produced more than a dozen works for the sold-out show at the Kim Foster Gallery, ranging from smaller projects (about 2,800 crayons) to several massive pieces made of 16,000 to 20,000 crayons each.

Whatever his subject, the imaginative and meticulous execution of his work is where Chris puts his energy–any “message” is best left to the voice of a well-crafted object. He believes that having a preconceived idea of what his work might mean isn’t necessarily wise or helpful. “Meaning comes from the object after you make it,” he says. “I like to create the object and then sit back and allow it to speak, or not speak. To have its own voice and power.”

But maybe the most powerful aspect of this work for most of us is the medium itself, the satisfying thrill of a fresh box of waxy crayons in a delicious assortment of colors. “Everyone feels an affinity for crayons,” Faur says. “Even in New York, where they’ve seen everything…people walk up and go ‘wow!’”

A Colorful World

In his pursuit of color as language, Faur developed a system that assigns a particular hue to each letter of the alphabet. Using this color alphabet, he can insert words, phrases, and ideas into images in ways that are descriptive, evocative, and sometimes subversive. He also uses the color alphabet to create graphic works of color text, for example this piece representing Hamlet’s soliloquy, translated into German. To translate your own thoughts into color, see his “alphabet converter” at christianfaur.com