Hunter Hughes ’14 felt at home the moment his gaze first met Swasey Chapel.

Hughes grew up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, a bucolic Detroit suburb with stately tree-lined streets. The main building on his high school campus, designed in the 1920s, features a red brick facade, limestone columns, and a bell tower topped with a cupola.

“It’s almost identical to Swasey,” said Hughes, an architect with Matthew Baird Architects in New York.

The paradox of Swasey Chapel, celebrating its centennial anniversary in 2024, is how distinctive it is to Denisonians — while being relatively indistinguishable from other campus chapels built in the same era.

Architect John H. Beyer ’54 says that’s not a knock on Swasey, which in his mind serves as the university’s de facto “logo.”

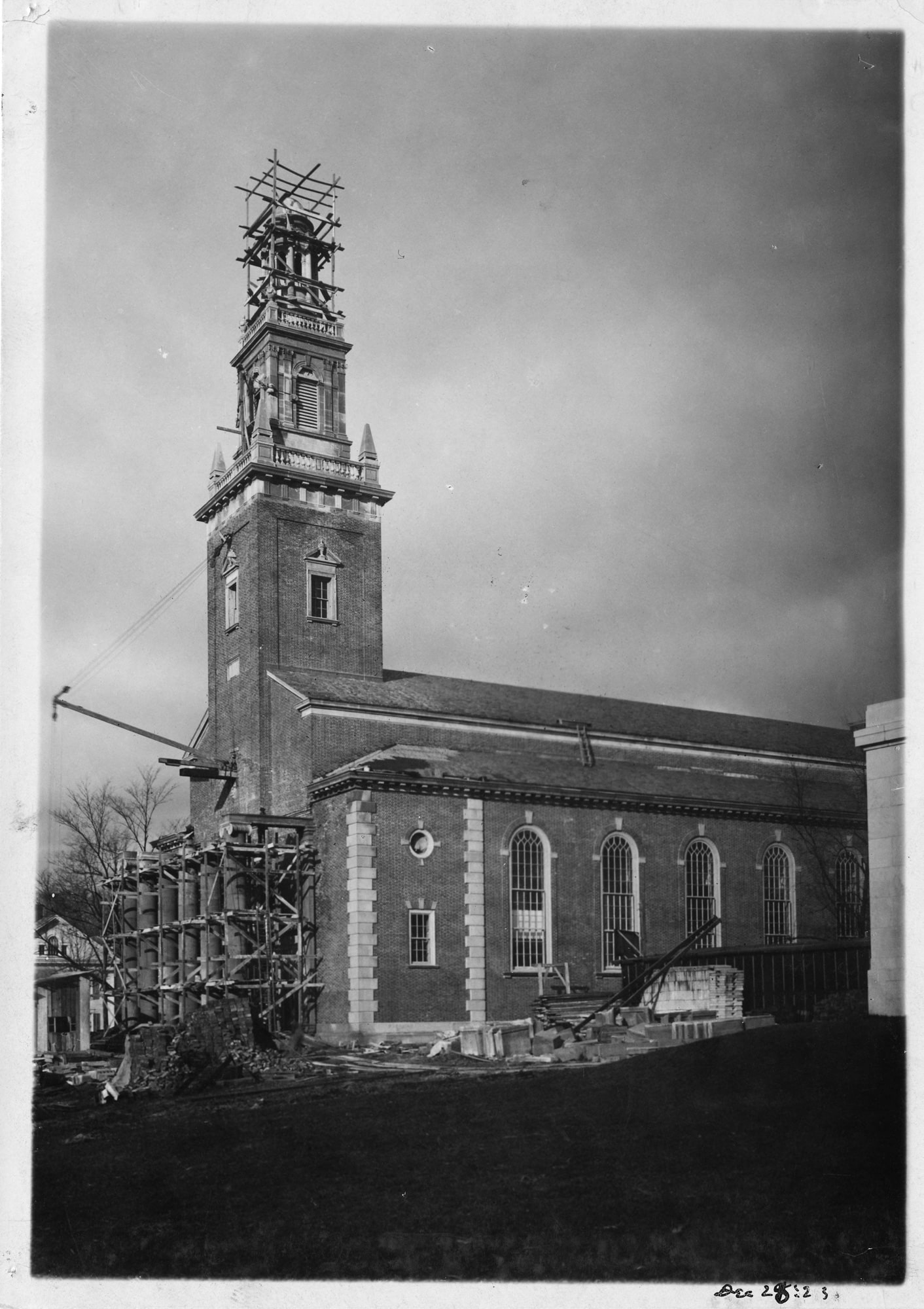

“The most important thing about Swasey Chapel is its symbolism, not its detailed architecture,” said Beyer, founding partner of Beyer Blinder Belle in New York. “Being on top of The Hill and being seen from afar, it represents the classic image of the whole university. That’s not a bad distinction for a building to hold.”

The idea to perch Swasey on the university’s highest point of land, coupled with subsequent decisions to keep it separate from academic and resident hall quadrangles, affords it visibility not enjoyed by chapels on some U.S. campuses.

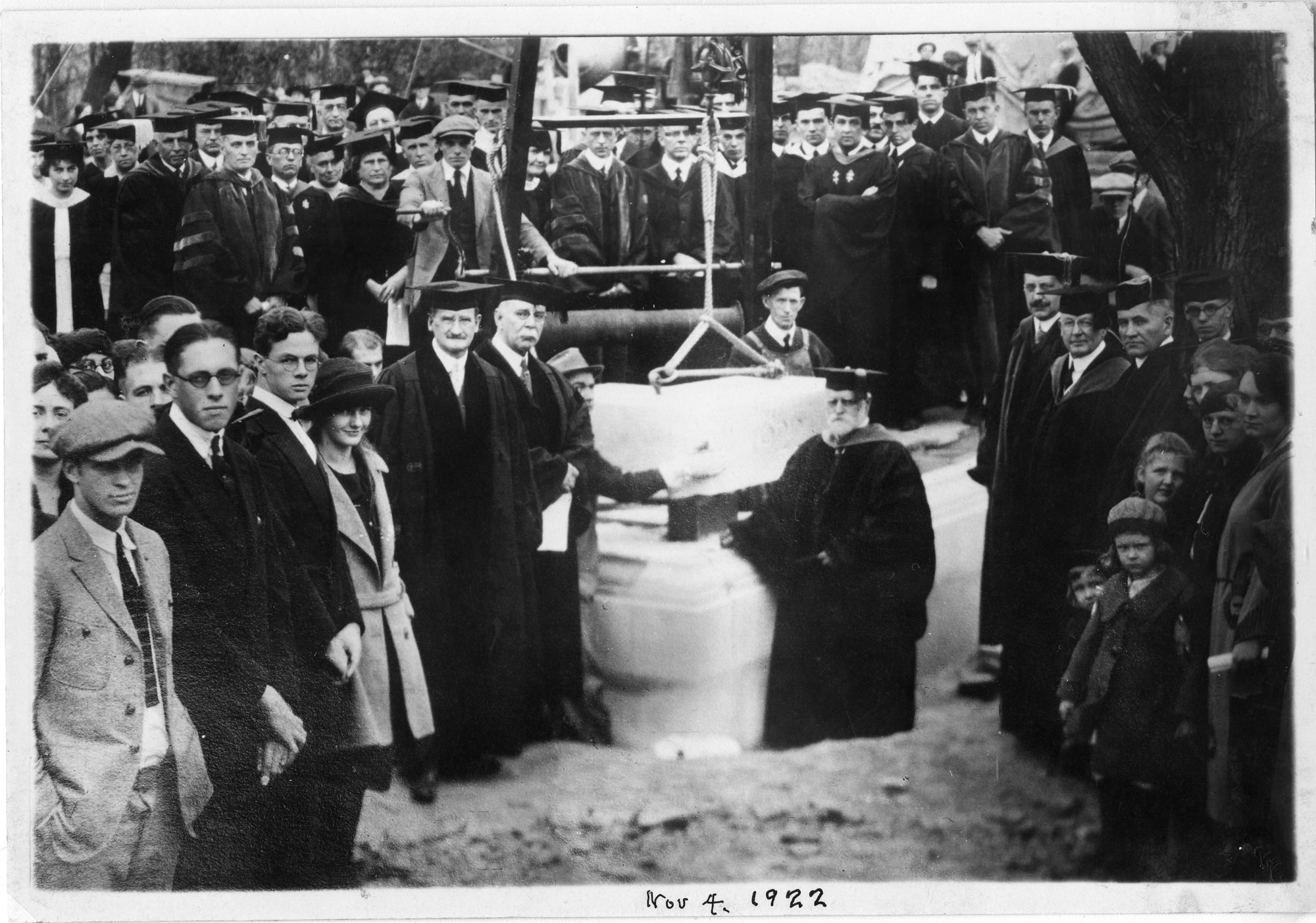

Mechanical engineering savant and former Denison trustee board president Ambrose Swasey donated $400,000 to build the chapel as part of the 1917 Greater Denison expansion project. Arnold Brunner was selected as the architect, and Frederick Law Olmsted Sons, whose founder designed New York’s Central Park, handled the architectural landscaping.

One trait of Olmsted designs was to leave a side of a campus quadrangle open to create scenic views. That was the approach to Denison’s academic quad, giving students, faculty, and staff a clear sight of Swasey.

“Any time you walk toward the chapel from either direction, it fills your line of vision because it’s not lost in a quadrangle,” said Beyer, whose firm transformed Denison’s old gymnasium into Bryant Arts Center in 2009. “Most campus chapels are just in a quadrangle. What makes Swasey special is you can see it from a distance.”

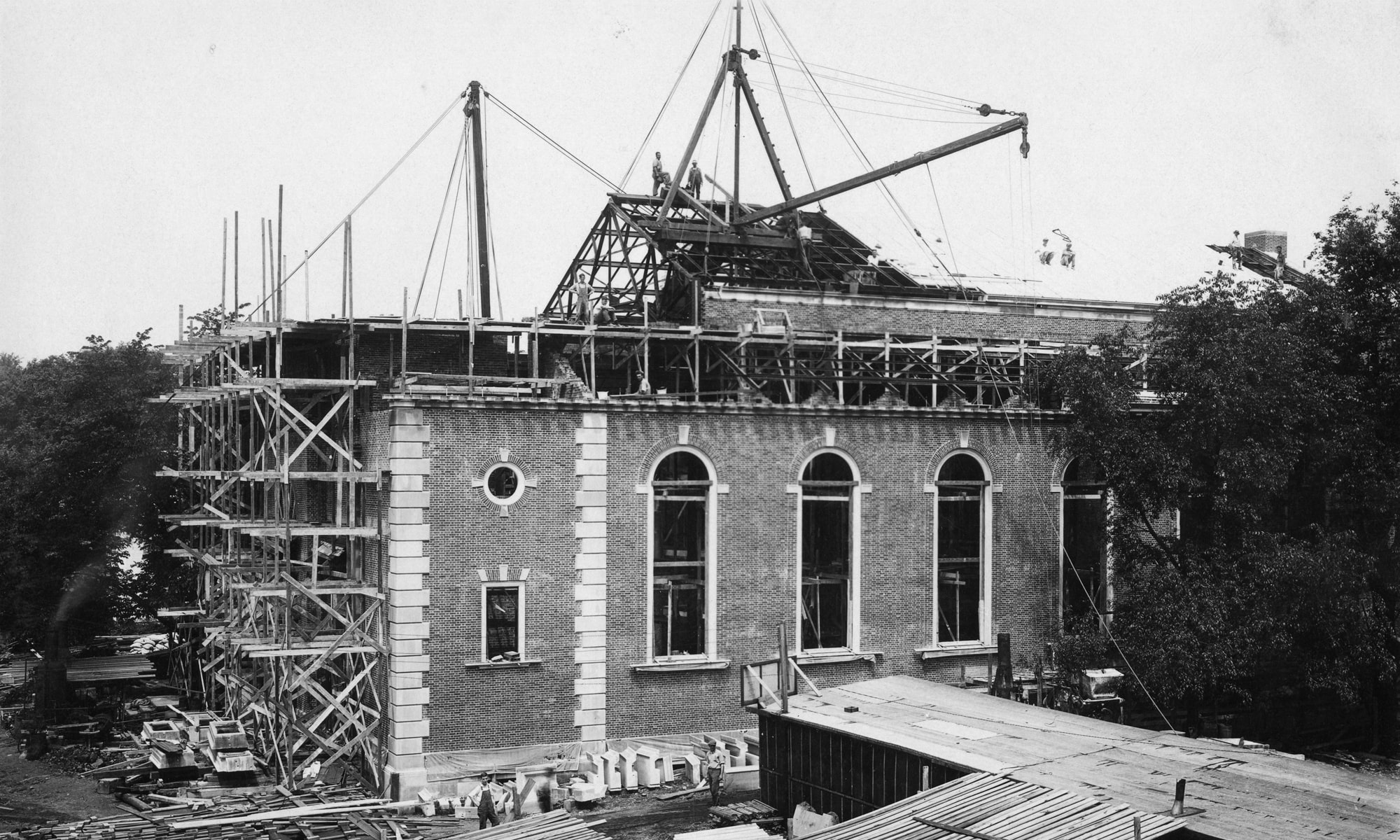

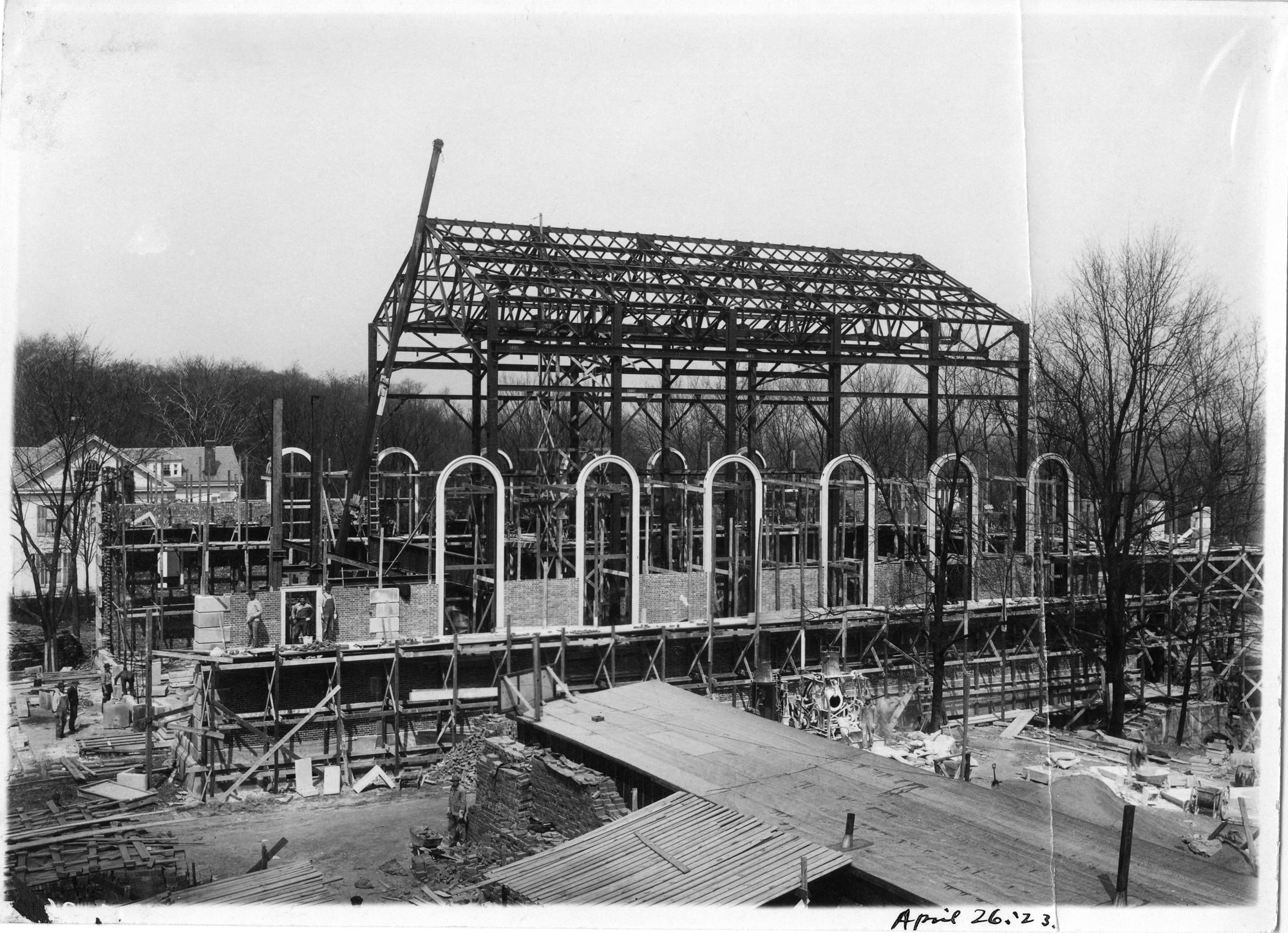

Chapel construction began in 1922 and was completed two years later. For budding tour guides and architecture wonks, Swasey’s exterior features Bedford limestone and Harvard brick laid in Flemish bond grace. The chapel stands 140 feet, 6⅝ inches tall (not counting the lightning rod), while six Ionic columns support the portico that faces Chapel Walk.

“After graduation, I went to London,” said David Anderson ’87, an architect for Miller Dyer Spears in Boston. “I had always thought of Swasey as a New England chapel, but walking around London, you see a lot of churches that kind of look like the chapel. Many were designed by Christopher Wren after the Great Fire of 1666.”

Anderson played percussion in the Denison symphony orchestra. He loves the intimacy of Swasey’s auditorium and how close the audience sits to its stage. He’s also aware of the one glitch not anticipated by its builders.

The chapel was designed for worship, not concerts. As Denison became a secular university in the 1960s, Swasey expanded its purposes to include high-profile lectures, academic award convocations, and musical and artistic performances.

Swasey has undergone many renovations to retain its appearance and charm, but improving the acoustics remains a challenge.

“We pull the curtains to absorb some of the sound during concerts,” said music professor Ching-chu Hu, director of the Vail Series. “We try to do little things to modernize the chapel. Most of the artists love performing there and they understand it was not built as a performing space.”

The chapel is ideal for big events such as the Vail Series. While Swasey limits capacity to 990 spectators to keep fire marshalls happy, it’s more than twice the size of Sharon Martin Hall in the Michael D. Eisner Center for the Performing Arts.

Anderson understands why Beyer, his fellow architect and alum, considers the chapel to be Denison’s logo. He recalls a time when Swasey was on the university’s official stationary.

“Swasey Chapel orients not only the campus, but the surrounding town, and does it beautifully,” Anderson said.

As an undergrad, he cherished the view of the chapel from his room on winter mornings.

“After an overnight storm, you would have one side of the cupola blasted with snow and ice and the other side getting hit with sunlight,” Anderson recalled. “It produced this amazing halo of light on the edges.”

Swasey Chapel remains an iconic venue to many alumni, Beyer said, because of the memories made inside its walls and what it represents institutionally.

“I don’t know if many students stand back and say, ‘Whoa, this is a significant piece of architecture,’” Beyer said. “They think of it as a symbol. What’s really important is what happened there and on campus. Seeing the performances, listening to the famous speakers, celebrating academic achievements. That’s what lives in memories.”