What was the original purpose of the Urban Tree Connection?

The organization was founded by a landscape architect, and the mission was rooted in transforming abandoned and vacant properties into productive community greening and gardening spaces. That had a significant relevance for the 20 years prior to my arrival at the organization, but conditions in Philadelphia have changed significantly. The city is rapidly gentrifying; some neighborhoods have seen gentrification push long-standing populations of Black and Latino people out completely.

For a long time, the Urban Tree Connection gardens squatted on vacant land, and that was no longer tenable because of rising demand for land, so the organization had reached a crisis point. There’s a lot of pressure on nonprofits to expand, to scale up and replicate your model. The organization had [done that] and we were all over the city, trying to build the infrastructure necessary to create community green spaces in different neighborhoods. But parks and gardens are only successful when residents maintain them — and we didn’t have the resources to develop a core base of people in every community to sustain those green spaces.

How has the organization’s mission shifted to respond to these changes and challenges?

We realized there are many different ways to think about growing our work. It became clear to me that our core area, where people showed up all the time to support our sites, was in one particular neighborhood: Haddington. We decided to focus on this neighborhood and test a theory that gardens and community farms can be used as a way to keep people in place despite gentrification. We don’t want our gardens to be used to attract new people whose arrival will push out longterm residents. We want to be a stabilizing force for the people who live in Haddington. So we have decided to deepen our work here in this neighborhood, rather than expanding further geographically.

Tell me more about the Haddington neighborhood.

It is a historically Black working class neighborhood in West Philadelphia. It is a pretty large area — from Girard Avenue up to Vine Street from 52nd Street all the way up to 63rd Street. Like many neighborhoods in Philly, it is so different from block to block. Around our farm at 53rd Street and Wyalusing Avenue, there’s third-generation families, homeowners who have lived there for years and know each other. And then around the garden on Pearl Street, it’s all Philadelphia Housing Authority property, predominantly renters. It’s a very vibrant community, with active block captains who host cleanups and block parties, and the 52nd Street commercial corridor has a lot of small, Black-owned businesses that have been really supportive of our work. Haddington has its challenges, but it is a special place with a real neighborhood feel. And there’s a lot of work to do to make sure it stays that way.

How do you design green space specifically for this community?

All of the spaces have been founded and developed with community members and are actively stewarded by those who live in the neighborhood. For instance, our farm was founded in 2009, when three block captains came to us concerned about an abandoned lot in the interior of a block. It used to be a chop shop, and it was filled with car parts and barrels of oil. Through a series of conversations, we landed on the idea of turning it into a community farm because of the high rates of food insecurity in the neighborhood.

Another site is our memorial garden, in a space where three young men were killed in the 1990s. One of the mothers wanted to honor her son’s life, and the lives of the other young men, and create a safe space for children in this place that had this history of violence — and by violence, I don’t mean interpersonal violence. I mean the systemic, economic violence of people losing their jobs, losing their homes, not having health care, and not having enough to eat.

Have the farms and gardens that the Urban Tree Connection helped to establish had an effect on food insecurity in Haddington?

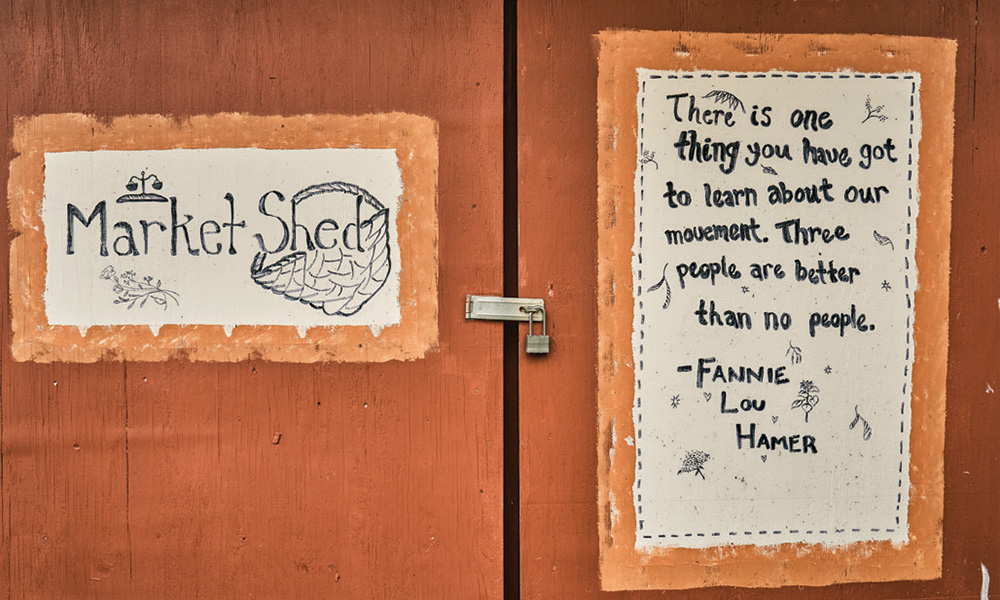

We grow between 4,000 and 6,000 pounds of food annually using all sustainable growing practices. We used to give all the food away for free, but one of the neighbors said, “I think people will want to invest in this as a community asset,” so we started our first farm stand in the neighborhood around 2011. We would accept SNAP and WIC, and we were training community members to run those farmer’s markets.

It was a really strong model. But when the pandemic hit, that was no longer feasible. It wasn’t safe, and a lot of people could no longer afford to pay anything. So we started to talk to the block captains who said, “What if we distributed the food?” We worked with six different blocks last year, with block captains delivering food door to door. It was so successful that we plan to build on the model. It makes sense because food insecurity doesn’t just impact one household, it impacts a whole community. In our neighborhood people really show up for each other and shoulder the burden together.

How can building community spaces like these help address issues of economic and social injustice?

Farms and gardens and land stewardship can be used as vehicles for keeping neighbors in place in their own communities, and they can also be vehicles for developing the leadership of Black and brown working-class people so they can have greater agency in their lives. Through the experience of growing food together in a cooperative environment where we have a shared goal of feeding our community, people are fundamentally transformed. They are producing a product that is meeting a need in their neighborhood, which is a very different experience than many people have in their work. Particularly in communities like Haddington — where many people are in parts of the workforce with the highest level of precarity, who are always in danger of losing their jobs, of not having healthcare, of not making enough to sustain themselves — what does it mean to think about labor differently?

What does success look like for the Urban Tree Connection?

Success is having an established, community governed food system in Haddington, and having land stewardship deeply embedded in the neighborhood. And it is having those things serve as a catalyst for people to become hungry for more say in their community, to think about how they might be able to work together to address other aspects of their lives. Parents organizing to shift things in their local schools, and neighbors organizing to increase safety on their blocks — success is having this neighborhood led by community members.