Much has been written about the 2020 presidential election, still a year away. I won’t rehearse those conversations here, their volume modulating between the jarring cymbal and the fatal bassoon. Instead, I want to point out the obvious: At this time next year, everything will be different. Let’s start first with personnel. No, not the Oval Office. I mean our Center for Learning and Teaching.

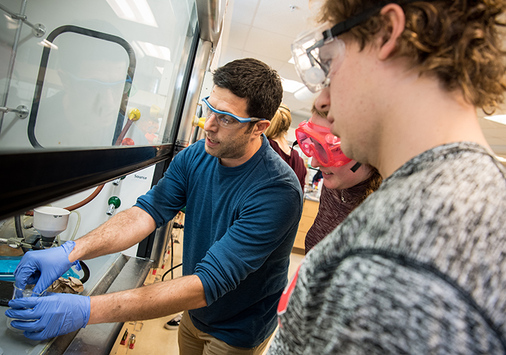

This is my final year directing the Center, which celebrates its five-year anniversary this spring. Some history: Dr. Frank Hassebrock, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, served as the Center’s inaugural director from 2015 to 2017. Under his leadership, the CfLT became the primary conduit connecting faculty to cutting-edge research on motivation, memory, and the neuroscience of how students learn. These emphases helped faculty create classroom experiences that ensured the learning stuck. Frank’s leadership was exemplary. Through word, example, and the diligent mining of evidence-based practices, he promoted a culture of collaboration and investment around the most important work we do here.

It’s important not to lose sight of this history, because it reminds us of what matters. And this history will serve like a beacon as the Center moves into its next five years, guiding us toward a horizon where everything is changing.

It’s that horizon which intrigues me. Because, it bears repeating, everything will be different a year from now. The Center’s new Director will be deeply immersed in helping sustain a culture of faculty development around learning and teaching. Yet how we teach students surely will continue to evolve, because our students are changing. (We know this based on brain research, sure, but also from the wider context beyond the lab, a context shaped by social media, pop culture, politics, and a nagging distrust many traditional-aged college students seem to share.)

I wonder too if faculty development may need to shift ever-slightly. Models that ask faculty to do more or to think differently or to learn from so-called “best practices” may be missing the mark. Faculty are at capacity, already giving so much across all three cells. Sustaining the excellence that is the hallmark of Denison may require us to ask different kinds of questions and risk on behalf of outcomes not yet known. The leadership of the College, at all levels, suggests we’re up to the task.

That horizon also has political hues. In anticipation of a vigorous primary season leading up to election day, I am mindful that our campus will be affected by what transpires in and across political circles beyond the Hill. How can it be otherwise? There is much I might say about next fall. I’ll close with three insights.

First, the norms, values, ideals, and practices central to our democracy have never mattered more. Recent examinations of why democracies fail provide theoretical and empirical fodder from which may be culled reasons both to despair and hope. Next November is the chance to say what each one of us believes at the ballot box. And here, I’d only reiterate Aaron Sorkin’s pithy wisdom.

And if you’re inclined, I hope you might read the works of Danielle Allen, whose thinking is a rigorous companion to Sorkin’s pith. Allen argues that ours is a thoroughly imperfect democracy; as such we will never be one people (the Latin phrase on our currency notwithstanding). But she recognizes, as the Founders did (thoroughly imperfect themselves), that a “more perfect union” is not about “perfection” in the sense we use the term today (i.e., flawless, seamless, ideal, without fault). “Perfect” in the 18th century meant something different, namely, “whole.”

When Senator Barack Obama challenged us to think harder about the ways race has always mattered, when he consoled us as president to imagine a more perfect union from the ashes of tragedy so profound as to be nearly unspeakable, he was reminding us that democracy must bend toward wholeness, that everyone belongs and everyone matters.

Second, if the horizon’s political hues promise difficult days, we would do well to remember who we’ve recently lost. Last month saw the passing of U.S. Congressman Elijah Cummings, who represented the great state of Maryland and the fine city of Baltimore for over two decades. Mr. Cummings’s accomplishments are too many to summarize here. But his life, movingly eulogized by Dr. Leana Wen, should inspire all of us to weave together the threads of obligation and commitment and belonging that unite us all. There are no small gestures. Every act of kindness matters. Courage on behalf of uncommon judgment matters. So too does the resolute conviction that joy cometh in the morning.

These values may not seem to ring true with the purposes of higher education, to the work of learning and teaching, but I would disagree. At its root, education means “to draw out.” While it is true that all of us aspire to draw from our students those acts of insight and creativity which may gesture toward confirming and affirming our respective disciplines, I cannot help but wonder whether the liberal arts—really, colleges like ours—beckon us toward different ends. If darkness looms on the horizon, how may liberal education, and the work we do as teachers-scholars-artists, share light?

Finally, when I struggle to find words to make sense of the thoroughly nonsensical, music helps. As of late, I’ve been listening to a lot of Taylor Swift (don’t judge). Because these times demand we live in hope, I offer the succor found in Stevie Wonder and Denison’s Ching-chu Hu. In these artists’ common struggle to give meaning to what matters,they remind us how we may see a way through pain, loss, and uncertainty. We must always remember that we need each other; that the names of those we’ve loved and lost should sear our hearts and compel us to make the world anew. No one gets to higher ground alone.